Want To Know About The World’s Largest Diamonds?

Largest Diamonds Ever Found! Jewelry Pros, See the 3106ct Cullinan & More

Úvod:

Are you curious about the world’s most massive diamonds? This comprehensive guide details legendary stones like the 3,106-carat Cullinan and the 1,758-carat Sewelô. Discover their origins in African mines, the intricate cutting process by master artisans, and their transformation into iconic gems for crowns and high jewelry. For jewelry professionals, designers, and retailers, this resource offers vital information on diamond weights, colors, clarities, and historic auctions—essential knowledge for sourcing, valuing, and creating with the Earth’s most extraordinary diamonds.

Obsah

Section I Overview of the World's Very Large Diamonds

Table 5-1 List of Notable Very Large Diamonds Weighing More Than 400 ct

| Žádný. | Diamond Name | Weight (ct) | Discovery Year | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cullinan | 3106.00 | 1905 | South Africa |

| 2 | Sewelô | 1758.00 | 2019 | Botswana |

| 3 | Unnamed | 1138.00 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| 4 | Lesedi La Rona | 1109.00 | 2015 | Botswana |

| 5 | Excelsior | 995.20 | 1893 | South Africa |

| 6 | Star of Sierra Leone | 969.80 | 1972 | Sierra Leone |

| 7 | Lesotho Legend | 910.00 | 2018 | Lesotho |

| 8 | Incomparable | 890.00 | 1984 | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| 9 | Unnamed | 880.00 | 1983 | Guinea |

| 10 | Constellation | 813.00 | 2015 | Botswana |

| 11 | Great Mogul | 787.00 | 1650 | Indie |

| 12 | Millennium Star | 777.00 | 1990 | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| 13 | Woyie River | 770.00 | 1945 | Sierra Leone |

| 14 | Golden Jubilee | 755.50 | 1985 | South Africa |

| 15 | President Vargas | 726.60 | 1938 | Brazil |

| 16 | Jonker | 726.00 | 1934 | South Africa |

| 17 | Peace | 709.41 | 2017 | Sierra Leone |

| 18 | Unnamed | 657.00 | 1936 | Brazil |

| 19 | Jubilee-Reitz | 650.80 | 1895 | South Africa |

| 20 | Unnamed | 630.00 | 1938 | Brazil |

| 21 | Unnamed | 620.14 | South Africa | |

| 22 | Sefadu | 620.00 | 1970 | Sierra Leone |

| 23 | Kimberley Octahedral | 616.00 | 1974 | South Africa |

| 24 | Baumgold | 609.25 | 1922 | South Africa |

| 25 | Lesotho Promise | 603.00 | 2006 | Lesotho |

| 26 | Santo Antônio | 602.00 | 1994 | Brazil |

| 27 | Lesotho Brown | 601.25 | 1967 | Lesotho |

| 28 | Goyas | 600.00 | 1906 | Brazil |

| 29 | Centenary | 599.00 | 1986 | South Africa |

| 30 | Unnamed | 593.50 | 1919 | South Africa |

| 31 | Spirit of de Grisogono | 587.00 | Central African Republic | |

| 32 | Unnamed | 572.25 | 1955 | South Africa |

| 33 | Unnamed | 565.75 | 1912 | South Africa |

| 34 | Canadamask | 552.74 | 2018 | Canada |

| 35 | Letšeng Star | 550.00 | 2011 | Lesotho |

| 36 | Unnamed | 549.00 | 2020 | Botswana |

| 37 | Unnamed | 537.00 | South Africa | |

| 38 | Unnamed | 532.00 | 1943 | Sierra Leone |

| 39 | Lesotho B | 527.00 | 1965 | Lesotho |

| 40 | Unnamed | 523.74 | 1907 | South Africa |

| 41 | Unnamed | 514.00 | 1911 | South Africa |

| 42 | Venter | 511.25 | 1951 | South Africa |

| 43 | Unnamed | 507.00 | 1914 | South Africa |

| 44 | Cullinan Heritage | 507.00 | 2009 | South Africa |

| 45 | Kimberley | 503.50 | 1914 | South Africa |

| 46 | Unnamed | 500.00 | 1976 | Central African Republic |

| 47 | Letšeng Legacy | 493.00 | 2007 | Lesotho |

| 48 | Baumgold II | 490.00 | 1941 | South Africa |

| 49 | Unnamed | 487.25 | 1905 | South Africa |

| 50 | Leseli la Letšeng | 478.00 | 2008 | Lesotho |

| 51 | Meya Prosperity | 476.00 | 2017 | Sierra Leone |

| 52 | Unnamed | 472.00 | 2018 | Botswana |

| 53 | Unnamed | 458.75 | 1907 | South Africa |

| 54 | Unnamed | 458.00 | 1913 | South Africa |

| 55 | Jacob-Victoria | 457.50 | 1884 | South Africa |

| 56 | Darcy Vargas | 455.00 | 1939 | Brazil |

| 57 | Unnamed | 444.00 | 1926 | South Africa |

| 58 | Unnamed | 442.25 | 1917 | South Africa |

| 59 | Nizam | 440.00 | 1835 | Indie |

| 60 | Zale Light of Peace | 434.60 | 1969 | Sierra Leone |

| 61 | Unnamed | 430.50 | 1913 | South Africa |

| 62 | Victoria 1880 | 428.50 | 1880 | South Africa |

| 63 | De Beers | 428.50 | 1888 | South Africa |

| 64 | Charncca I | 428.00 | 1940 | Brazil |

| 65 | Unnamed | 427.50 | 1913 | South Africa |

| 66 | Niarchos | 426.50 | 1954 | South Africa |

| 67 | Unnamed | 419.00 | 1913 | South Africa |

| 68 | Berglen | 416.25 | 1924 | South Africa |

| 69 | Brodrick | 412.50 | 1928 | South Africa |

| 70 | Pitt | 410.00 | 1701 | Indie |

| 71 | Unnamed | 409.00 | 1913 | South Africa |

| 72 | President Dutra | 407.68 | 1949 | Brazil |

| 73 | Unnamed | 407.50 | 1926 | South Africa |

| 74 | 4 de Fevereiro | 404.20 | 2016 | Angola |

| 75 | Coromandel VI | 400.65 | 1948 | Brazil |

| 76 | Unnamed | 400.00 | 1891 | South Africa |

Table 5-2 Overview of Major Diamonds Produced by Each Country

| Region | Country | Množství | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | South Africa | 37 | 48.68 |

| Sierra Leone | 7 | 9.21 | |

| Lesotho | 7 | 9.21 | |

| Botswana | 5 | 6.58 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 3 | 3.95 | |

| Central African Republic | 2 | 2.63 | |

| Guinea | 1 | 1.32 | |

| Angola | 1 | 1.32 | |

| South America | Brazil | 9 | 11.83 |

| Asia | Indie | 3 | 3.95 |

| North America | Canada | 1 | 1.32 |

Section II Very Large Diamonds Produced in South Africa

1. The Preeminent Cullinan Diamond

The Cullinan Diamond is the largest diamond ever discovered in the world and was found at South Africa’s famous Premier diamond mine. Its discovery is also the greatest miracle in the history of diamond discoveries.

(1) The Discovery of the Premier Diamond Mine

In the history of diamond exploration, the discovery in the 1880s of primary kimberlite diamond deposits in the Kimberley region of central South Africa was a breakthrough and a milestone. The discovery of a primary diamond deposit in the northeastern Transvaal, however, was a very accidental event. Before the discovery of primary deposits in Kimberley, diamonds found elsewhere were all alluvial resources.

At that time, a miner named Percival White Tracey, who had worked at the De Beers mines in the Kimberley area, went to Johannesburg and joined the gold prospectors. The gold seekers found gold-bearing reefs along the Witwatersrand, but they did not understand the relationship of those rocks to the gold deposits or the sedimentary characteristics of the rocks. Tracey was different: while panning for gold in a stream, he noticed that the detritus in his pan resembled what he had seen at the diamond mines in the Kimberley region.

So he rowed a small boat up the stream, tracing the source of the detritus, and unknowingly entered the Elandsfontein estate. There, he found a small hill whose outward appearance was very similar to the small hills surrounding the diamond mines in Kimberley. Relying on intuition and experience, he judged that this might be another diamond-bearing hill. But Tracey could not go far because the owner of Elandsfontein, Joachim Prinsloo, was a Boer who held a deep prejudice against prospectors; he hated trespassers and might shoot unlicensed entrants. He had previously owned an estate at Madderfontein but was forced to sell it during the 1886 gold rush and had reluctantly moved to Elandsfontein. Now that diamonds had been found here, he was extremely unfriendly to prospectors and diamond seekers.

For the reasons above, Tracey had no choice but to retreat. Meanwhile, the estate owner, Prince Road, continued farming on the barren, desolate land and rented out portions of it to locals for cultivation. To continue pursuing his “dream” of tracking diamonds, Tracey thought of the famous Johannesburg building contractor, Thomas Cullinan. This man had a keen interest in finding diamonds and had even predicted that the Transvaal might yield diamonds; moreover, Cullinan was very skilled in trade negotiations. For this reason, the two of them, under various pretexts, visited the estate owner, Prince Road.

Cullinan hoped Prince Road would give them three months to carry out a preliminary survey of the estate; if the underground mineral resources met his requirements, he would buy the entire estate. Such a request was clearly unacceptable to the estate owner: he not only prevented the surveyors from working on his land, but also did not believe they could find any valuable mineral resources on the estate. Therefore, Prince Road set a price of £25,000 to sell the estate, a sum 50 times what he had paid for it.

The two sides agreed on terms, but before any substantive transaction took place, the Boer War broke out between the British Empire and the Transvaal and Orange Free State (1899–1902). Communications were cut off during the war, so the two parties could not be contacted. After the war ended, Cullinan renewed his request to purchase, but the estate owner raised the asking price for the estate to £50,000, leaving Cullinan with no choice. Eventually, the parties closed the deal, and with additional costs, Cullinan paid a total of £52,000 to buy the Elandsfontein estate. In October 1902, exploration commenced, and the first pit produced magnesian almandine and olivine, minerals commonly associated with diamonds and typically distributed around diamond deposits in roughly circular areas. The second pit yielded 11 diamonds, one of which weighed 16ct.

The Premier (Transvaal) Diamond Mining Company was established in 1903. The diamond deposit found at Elandsfontein thus became known as the Premier diamond mine. In the first two years of mining, the mine produced four exceptional diamonds over 400 ct, two diamonds of 200~300 ct, sixteen diamonds of 100~200 ct, and in 1905 it produced an extraordinary stone—the Cullinan diamond—so Cullinan’s investment paid off handsomely.

(2) The Discovery of the Cullinan Diamond

January 25, 1905, is one of the most memorable days in the history of diamond discovery. At dusk that day, the miners, who had laboured in the setting sun all day, were dragging their tired bodies, covered in sweat and dust, slowly back toward their temporary huts. Frederick G. S. Wells, the mine overseer, was among them, strolling along slowly, keeping an eye on the workers while waiting for the call to stop work. When he happened to walk to the edge of a pit, he suddenly noticed a sparkling stone at the top of the pit; in the sunset, this stone glittered and caught his eye. He instinctively thought he had struck “good luck” and found the sought-after diamond. He hurriedly bent over, lay down, and used the small knife he carried to gently pry the glittering stone out, and a miracle occurred. It was a sparkling diamond crystal, about the size of an adult’s fist. He stood there stunned, unable to contain his excitement, and jumped up, hardly believing his eyes, for before this he had never even seen a piece of diamond, let alone a whole one. He carefully hid the diamond in his coat, walking along while murmuring to himself: This cannot possibly be a large diamond!

However, what Wells had indeed found was an exceptionally large diamond, unprecedented in the history of diamond discoveries, weighing 3106ct. It was the largest diamond in the world, more than three times the weight of the then-largest diamond. “most noble” diamond. That very night, the huge diamond was placed in the mine’s safe, and the matter was reported to the company’s chairman, Thomas Cullinan.

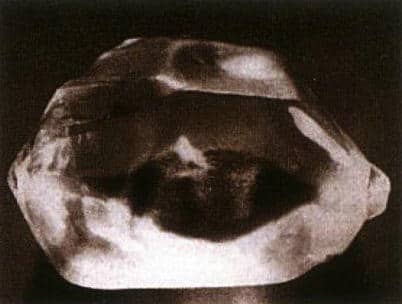

Cullinan, looking at the enormous diamond on his desk, was overjoyed and exceedingly delighted. Beaming with pleasure, he rewarded Frederick Wells; under the admiring gazes of all, Wells received a generous prize of £2,000 from Cullinan’s hand. Cullinan named the diamond after himself (Cullinan Diamond, Fig. 5-1), thus immortalizing his name in the annals of diamond history.

(3) Sale of the Cullinan Diamond

Selling the enormous Cullinan diamond was not an easy task. At that time, potential buyers in the world who could afford this gigantic gem were very few. Therefore, the usual approach to selling such a large diamond was to cut it into smaller stones, which could effectively lower the selling price per diamond; but that would inevitably damage the singularity, rarity, and uniqueness of the great diamond—this was a dilemma. Because large diamonds are rare and not easily found, selling the Cullinan diamond without destroying its uniqueness required waiting for the right moment. In the course of selling the Cullinan diamond, it did not suffer this “misfortune.” The Boer War had ended, and Louis Botha, the Boer general who was then Prime Minister of the Transvaal government, decided to buy the Cullinan diamond and present it to the British King Edward VII as a gift to secure the protection of the British Empire. The gift was for the King’s 66th birthday (November 9 1907). The Transvaal government spent a total of £175,000 for this purpose. The British King accepted this generous gift, and the diamond would travel from its place of origin in South Africa to Britain.

Transporting the priceless Cullinan diamond from South Africa to Britain was not a simple matter; the primary concern was security and theft prevention. The British specially dispatched fully armed soldiers and used a specially guarded transport vehicle to carry the great gem to London. In fact, the soldiers were escorting only a replica of the giant diamond, while the real Cullinan diamond was tucked inside an ordinary parcel sent to London.

(4) Cutting of the Cullinan Diamond

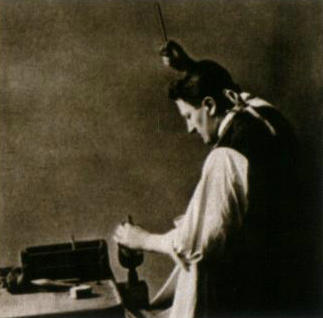

After King Edward VII took possession of the Cullinan Diamond, he decided to cut the enormous stone into gem diamonds. He commissioned the then most famous Dutch diamond-cutting firm, Asscher Brothers, which had cut the “Noble Grand” diamond a few years earlier. The cutting of the Cullinan Diamond was carried out personally by Joseph Asscher (1871– 1937). He travelled to London to examine the great diamond closely, placed it in his waistcoat pocket, and took it back to the workshop in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Before beginning the actual cutting, he applied his mind and every effort, spending six months conducting a detailed study of the stone, designing different cutting schemes, and performing dozens of simulated experiments on corresponding replicas in order to complete the task as well as possible.

After repeated study and experiments, Asscher chose to cleave the diamond. Although diamonds are very hard, they have cleavage. Therefore, if struck hard along a cleavage plane, a diamond will split along that plane. For the Cullinan Diamond, deciding along which cleavage plane to split it was a problem Asscher had to consider and confront to minimize waste and obtain the largest total weight, the greatest number, and the best optical performance of modern-cut diamonds.

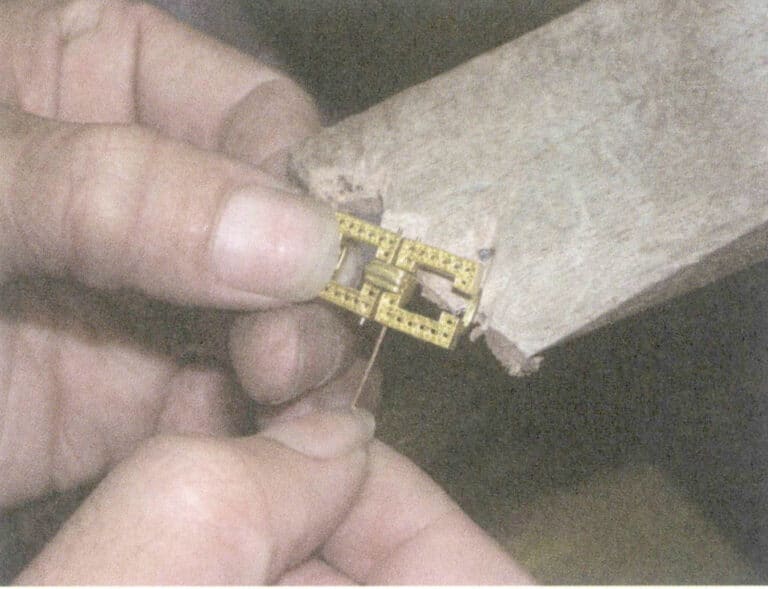

Asscher selected the direction and marked the rough diamond with traditional Indian ink. At one end of the marked line, he cut a “V”–shaped notch with another diamond — a common method for cleaving diamonds. The only exception for the Cullinan was that a larger cutting tool was required.

On February 10, 1908, with everything prepared, Asscher began cutting the Cullinan Diamond. He used the edge of a sharp steel blade as a wedge, placed it in the” “–shaped notch, the diamond having been glued to a support and firmly fixed to the workbench. The largest diamond in the world would be split in two by a single, simple strike from Asscher; one can imagine the tension at the time. If the diamond did not split along the predicted plane, the best and largest cut diamonds could not be produced, and Asscher bore great expectations and responsibility. He steadied the support with his left hand, raised a specially shaped wooden mallet in his right, and struck the top of the steel blade swiftly with the mallet. The diamond split exactly along the intended plane (Fig. 5–2), and Asscher breathed a sigh of relief.

(5) Famous Diamonds in the World Derived from the Cullinan Diamond

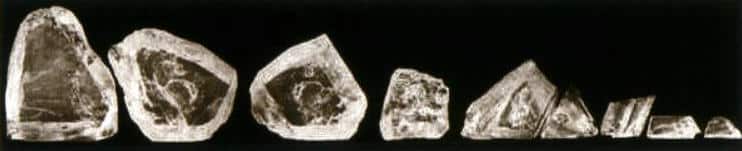

The nine famous finished diamonds cut from the Cullinan diamond are respectively called Cullinan I (also known as the Star of Africa) through Cullinan IX, all belonging to the British Crown Jewels (see Table 5-3).

Table 5-3 Characteristics of Cullinan I through Cullinan IX diamonds

| Žádný. | Název | Weight (ct) | Střih | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cullinan I (The Star of Africa) | 530.20 | Pear | Set in the British Sceptre with Cross |

| 2 | Cullinan II | 317.40 | Cushion | Set in the front of the British Imperial State |

| 3 | Cullinan III | 94.40 | Pear | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 4 | Cullinan IV | 63.70 | Cushion | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 5 | Cullinan V | 18.85 | Srdce | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 6 | Cullinan VI | 11.55 | Marquise | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 7 | Cullinan VII | 8.77 | Marquise | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 8 | Cullinan VIII | 6.80 | Cushion | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

| 9 | Cullinan IX | 4.39 | Pear | Part of the British Crown Jewels |

The characteristics of each finished diamond are as follows.

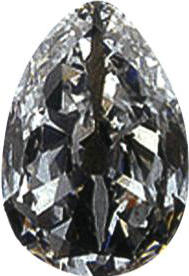

① Cullinan I (also called the Star of Africa). The diamond is cut with 76 facets in a pear-shaped cut, measuring 58.9mm×45.4mm×27.7mm, weighing 530.20 ct. The cut Cullinan I is set in the Sovereign’s Sceptre (Figure 5-4). The diamond is D colour, has a feather and an extra facet in the pavilion, and a clarity grade of Internally Flawless. It shows no fluorescence under long-wave ultraviolet light, but a faint greenish-white fluorescence under short-wave ultraviolet light, and exhibits a faint green phosphorescence.

② Cullinan II. The diamond is cut with 68 facets in an elongated modified brilliant-cut (step-cut) shape, measuring 45.4mm×40.8mm×24.2mm, weighing 317.40 ct. The cut Cullinan II diamond is set in the front of the British monarch’s crown (Fig. 5-5). The diamond is in colour, has a small nick on the girdle, a hairline feather on the table and star facets, two nearly parallel fissures on the star facets and pavilion facets near the girdle, and an extra facet; there are some scratches on the table. The clarity grade of the diamond is nearly flawless. Its fluorescence characteristics are the same as those of the Cullinan I diamond.

③ Cullinan III. The diamond is pear-shaped, weighing 94.40 ct (Fig. 5-6).

④ Cullinan IV. The diamond is cut in an elongated modified brilliant-cut (step-cut) shape, weighing 63.70 ct (Fig. 5-6).

⑤ Cullinan V. The diamond is heart-shaped, weighing 18.85 ct (Fig. 5-7).

⑥ Cullinan VI. The diamond is cut in an oval shape, weighing 11.55 ct (Fig. 5-8).

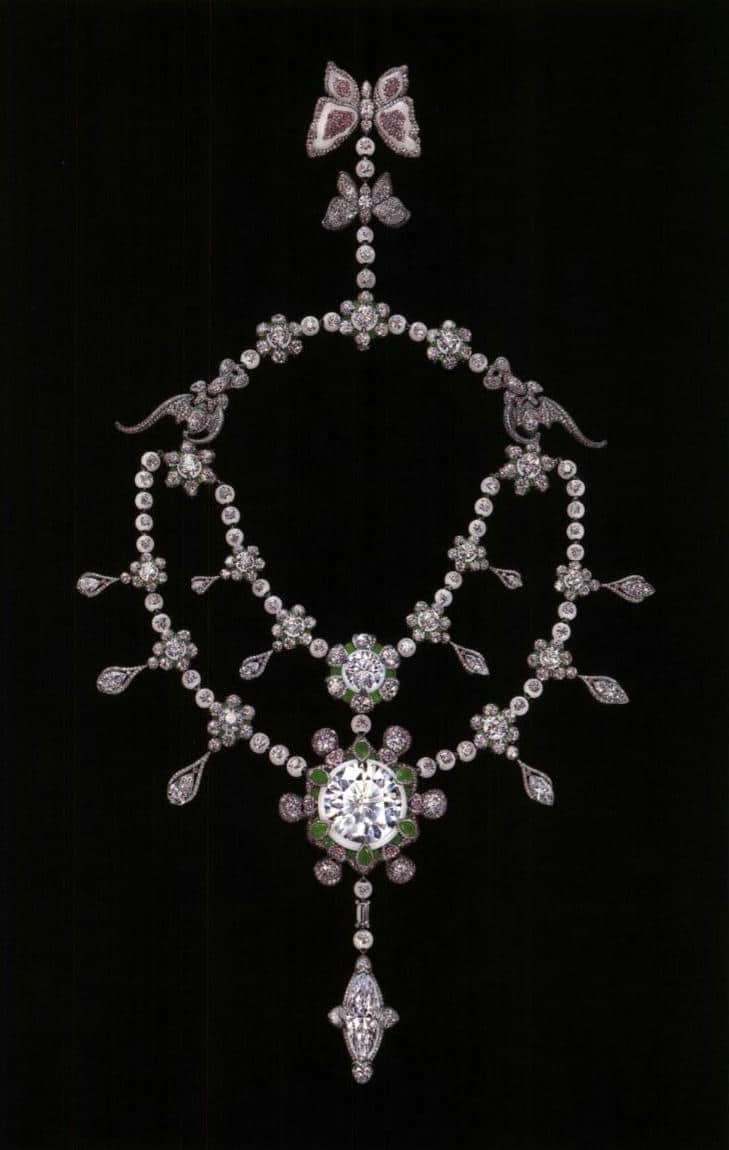

⑦ Cullinan VII. The diamond is cut in an oval shape, weighing 8.77 ct. It was used as the pendant on the Delhi Durbar Necklace, which is set with emeralds and diamonds (Fig. 5-9).

⑧ Cullinan VIII. The diamond is an elongated octagonal step cut, weighing 6.80 ct (Fig.5–8).

⑨ Cullinan IX. The diamond is pear-shaped, weighing 4.39 ct, and is set in a platinum ring (Fig.5–10).

Figure 5-5 The Cullinan II diamond is mounted on the front of the British Imperial State Crown (centered below)

Figure 5-6 The Cullinan III diamond (below) and the Cullinan IV diamond (above)

Figure 5-7 A brooch made with the Cullinan V diamond

Figure 5-8 Brooches made with the Cullinan VI diamond (below) and the Cullinan VIII diamond (above).

Figure 5-9 The Delhi Durbar Necklace (the pendant diamond is Cullinan VII)

Figure 5-10 The platinum ring set with the Cullinan IX diamond

2. The Excelsior Diamond

(1) The Discovery of the Jagersfontein Diamond Mine

The discovery of the Jagersfontein mine is closely linked to a man named De Klerk. At the time, he was the head of plantation operations on the Jagersfontein estate and happened to hear, from gold panners who had worked along the Vaal and Orange rivers, news of diamond finds. This report sparked great interest among many prospectors; word spread rapidly, and countless hopefuls, dreaming of striking it rich, joined the search for diamonds. But very few were actually lucky enough to find any. Amid this rush, De Klerk decided to try his luck on the estate. He dug down a few meters and soon reached a layer of ancient riverbed gravel. He washed the gravel and sand from that layer in a sluice and found garnets—minerals commonly associated with diamonds. Knowing that garnets are related to diamond formation, he persisted, and before long, fortune smiled on him: he discovered a diamond weighing 50 ct.

Once De Klerk’s discovery became known, it sparked a rush of more prospectors to the area. They pooled resources in mutual aid groups and jointly purchased land on the estate, believing it to be a mine with significant resource potential, and together formed a mining company. They also signed related agreements with Werner and Beit, partners of Cecil Rhodes, the founder of De Beers. The agreement stipulated the sale of all diamonds recovered from the Jagersfontein diamond mine between July 1892 and June 30, 1893, and it specifically set the average price per carat.

(2) The Discovery of the Excelsior Diamond

The discovery of the Excelsior diamond was rather dramatic. On June 30, 1893, just as the agreement above was about to expire, the miners were still working in groups as before, labouring incessantly, while the overseers wandered about, each attending to his duties. It was at that moment that one overseer happened to notice something unusual: a miner had quietly slipped away from the group, periodically stopping his work and looking around, observing the terrain around the mining area. At that moment, the foreman immediately became more vigilant; to more clearly monitor the miner’s strange behaviour, the foreman kept changing his vantage point. However, when the foreman’s attention wavered even slightly, the suspicious miner suddenly vanished from his sight, and it was not yet quitting time. The foreman hurried to ask the other miners; no one knew the missing miner’s whereabouts, and they were all very afraid. The miners well knew that the punishment for stealing diamonds was extremely severe, and none of them wanted to be implicated. They searched the entire mining area, but still could not find the missing miner.

As time passed, just half an hour before midnight — the very moment the agreement above was about to expire — the mysteriously missing miner suddenly appeared before the mine owner. He handed the large diamond he had found to the mine owner with his own hands, explained the reason for his brief absence, and asked the owner to reward him.

Thus, the largest diamond in the world at that time was dramatically handed to the mine owner. The owner was very pleased, rewarded him with £500, a horse and some tools, and sent a guard to escort the miner home.

(3) The Sale of the Excelsior Diamond

According to the terms of the agreement, the mine owner handed the diamond to Wena and Bate; the diamond was worth £50,000. This diamond was not only the largest discovered in the world at that time but also a high-quality stone. Its shape was flat on one end and bulging on the other, resembling a rough, small loaf. The colour of the diamond was white, but under sunlight or lights containing ultraviolet, it often exhibited a blue fluorescence, making its surface appear “blue-white.” This is a typical characteristic of diamonds from the Jagersfontein mine, and in the diamond trade, it is often called a “Jager.” In the British diamond colour grading system, a “Jagers” refers to diamonds of the highest colour grade.

Weina and Bette were fortunate to obtain the largest and finest diamond in the world at the time, but they also faced a new problem: no one in the world could afford to buy the stone. Although the Shah of Persia and various Indian princes showed great interest in purchasing it, no sale was ever completed. The diamond could only lie in a safe while awaiting a buyer. In 1903, the owner of the diamond concluded that the rough stone would be hard to sell as it was. Therefore, he decided to have it cut and then seek a buyer. At that time, Amsterdam in the Netherlands was the world centre for diamond cutting, and the Asscher brothers’ company had a long-standing reputation in the trade. Hence, the owner selected that firm to perform the cutting.

(4) Cutting of the Excelsior Diamond

The actual cutting work was carried out by Abraham Asscher (1880–1950) and Henry Koe. The two had clear divisions of labour, with Asscher responsible for cleaving and Henry Koe is responsible for grinding and polishing. After many careful studies, the plan was to split the diamond into 10 rough stones. Based on the research, Asscher marked the diamond with traditional ink and performed the cleaving; the three largest roughs weighed 158 ct, 147 ct, and 130 ct, respectively. Henry Koe handled the subsequent polishing; the diamond was ultimately cut into 21 finished stones, the largest 11 of which were named Excelsior I and Excelsior XI (see Table 5-4). The total weight of the finished stones was 373.75 ct, with a yield of approximately 37.56%.

Table 5-4 Overview of 11 Large Finished Diamonds Cut from the Excelsior Diamond

| Název | Weight (ct) | Střih | Název | Weight (ct) | Střih |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excelsior I | 69.68 | Pear | Excelsior VII | 26.30 | Marquise |

| Excelsior II | 47.03 | Pear | Excelsior VIII | 24.31 | Pear |

| Excelsior III | 46.90 | Pear | Excelsior IX | 16.78 | Pear |

| Excelsior IV | 40.23 | Marquise | Excelsior X | 13.86 | Pear |

| Excelsior V | 34.91 | Pear | Excelsior XI | 9.82 | Pear |

| Excelsior VI | 28.61 | Marquise |

Kopírování @ Sobling.Jewelry - Výrobce šperků na zakázku, továrna na šperky OEM a ODM

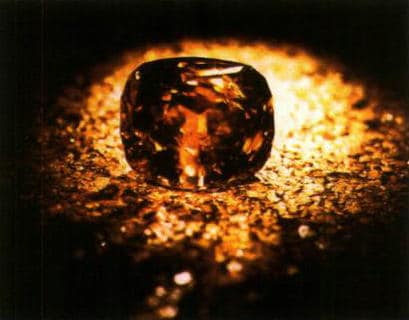

3. The Unique Golden Jubilee Diamond

The Golden Jubilee diamond was discovered in 1985 at South Africa’s famous Premier mine; the rough stone weighed 755 ct.

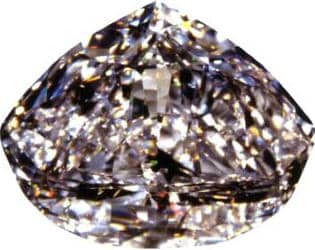

De Beers invited the world-renowned diamond cutter Gabriel Tolkowsky to oversee the cutting. After repeated study, Tolkowsky designed the diamond as a fire rose cushion cut and began cutting on May 24, 1988; the entire cutting process took two years. The finished diamond weighed 545.67 ct, making it currently the largest cut diamond in the world (Fig. 5– 12).

4. The Peerless Jonker Diamond

(1) The Discovery and Trade of the Jonker Diamond

The Jonker diamond was discovered in 1934 on the estate of Jacobus Jonker, about 5 km from the Premier diamond mine. For many years, the estate owner Jonker used his land as a base for searching for diamonds, spending much time on it and enjoying the pursuit. Day after day, he searched his estate for diamonds, but found little. Fortune turned in January 1934, when Jonker finally discovered a very large diamond on his estate, weighing 726.00 ct, and named it after himself (Figs. 5-13, 5-14). The diamond was about the size of an ordinary egg, pure white and flawless — a high-quality stone.

Figure 5-13 The Jonker diamond

Figure 5-14 Famous American movie star Hedy Lamarr holding the Jonker diamond

(2) Cutting and Polishing of the Jonker Diamond

In 1936, Winston handed the diamond to Lazare Kaplan, the inventor of the standard round brilliant cut—Marcel Tolkowsky’s cousin. In 1903, he founded Lazare Kaplan Diamond Company in Antwerp, Belgium, specializing in diamond cutting; as the business grew, he later opened a diamond cutting company in New York, USA. This was the largest diamond Kaplan had encountered in his career; cutting such a huge stone was also a severe challenge for him. To that end, he spent several months carefully observing and examining the diamond’s internal and external features and made several similar diamond models for simulation experiments. After thorough preparation, cutting began on April 27, 1936. First, a piece of rough stone weighing 35.82ct was cut from the crystal and fashioned into a finished diamond weighing 15.77 ct with an olive cut. Thereafter, twelve more pieces of rough were taken from the crystal and cut into finished stones. The Jonker diamond was cut into 13 flawless diamonds: 11 emerald cuts, one olive cut, and one cushion cut, with a total finished weight of 376.08 ct and a yield as high as 51.80%, see Table 5–5.

Table 5-5 Overview of Finished Diamonds Cut and Polished by Jonker

| Ne | Rough Weight (ct) | Estimated Cut Weight | Actual Weight After Cutting | Cut Style | Weight Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35.82 | 17 | 15.77 | Marquise | VIII |

| 2 | 79.65 | 42 | 41.29 | Emerald | II |

| 3 | 43.30 | 20 | 19.76 | Emerald | VII |

| 4 | 54.19 | 30 | 25.78 | Emerald | V |

| 5 | 52.77 | 35 | 30.71 | Emerald | IV |

| 6 | 65.28 | 35 | 35.45 | Emerald | III |

| 7 | 13.57 | 6 | 5.70 | Emerald | XI |

| 8 | 53.95 | 25 | 24.91 | Emerald | VI |

| 9 | 10.98 | 5 | 5.30 | Emerald | XII |

| 10 | 220.00 | 150 | 142.90 | Emerald | I |

| 11 | 29.46 | 14 | 11.43 | Emerald | X |

| 12 | 27.85 | 14 | 13.55 | Emerald | IX |

| 13 | 8.28 | 4 | 3.53 | Cushion | XIII |

(3) Trading of Finished Diamonds from the Jonker Diamond

After cutting, the Jonker diamonds yielded 13 finished stones. They were named in order according to their weights as “Jonker I” through “Jonker XIII.” The largest, “Jonker I,” was an emerald-cut diamond weighing 66 facets. Later, this diamond was recut by Winston into a single emerald-cut stone with 58 facets, weighing 125.35ct. In 1949, then King Farouk of Egypt purchased the diamond on credit for $1,000,000. After Farouk was overthrown in 1952, the Jonker diamond’s whereabouts were briefly unknown. It was later confirmed that the diamond was sold for $100,000 to Queen Ratna of Nepal. In 1977, Jonker I was sold in Hong Kong for $2,259,400 to an unnamed businessman.

It was reported that Indian princely rulers bought Jonker V, Jonker VII, and Jonker XI. Rumour has it that John D. Rockefeller purchased Jonker X. On October 16, 1975, a platinum ring set with Jonker IV appeared at Sotheby’s in New York and was purchased by a South American collector for about £276,600. It was auctioned again in New York in December 1987, selling for $1,705,000. Jonker II was sold at Sotheby’s in Geneva in May 1994 for $1,974,830.

5. The Unique Jubilee — Reitz Diamond

Jubilee–Reitz is an irregular octahedral diamond with a rough weight of 650.80 ct. It was discovered in 1895 at the Jagersfontein diamond mine in the Kimberley region of South Africa, the same source as the incomparable diamonds. After a London diamond syndicate acquired the diamond, they named it the “Reitz Diamond” in honour of Francis William Reitz, then President of the Orange Free State.

In 1896, the syndicate sent the stone to Amsterdam in the Netherlands, where a then-famous diamond cutter worked on it. The cutting method was unusual: first, a roughly 40 ct parcel of the rough was cut out and then polished into a finished 13.34 ct diamond, named the Bea Jayep (Bea Jejep) diamond; this stone became famous for a time and was owned by King Dom Carlos I of Portugal, who gave it to his wife. Unfortunately, the whereabouts of that diamond are unknown today. The remaining rough was cut and polished into a long, pointed step-cut diamond weighing 245.35 ct (Fig. 5-15). The diamond was named Jubilee to commemorate Queen Victoria’s 60th anniversary on the throne in 1897; the diamond has 88 facets.

In 1900, the London diamond syndicate exhibited the stone at the Paris Exposition, where it was then valued at 7 million francs. Shortly thereafter, it was purchased by Indian magnate Dorabji Tata. In 1937, the diamond came into the possession of the Frenchman Paul-Louis Weiller, who frequently lent the Jubilee for exhibitions; for example, in 1960, Weiller lent the diamond to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. In 1966, it was loaned for display at the De Beers Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Robert Mouwan is the current owner of the Jubilee–Reitz diamond; it is presently the largest among his extensive collection. He graded the diamond’s colour as near the highest colour grade for colourless diamonds, with a clarity of VVS2. He has said: “When it comes to human efforts made for diamonds, my favourite is the Jubilee–Reitz diamond, because its cutting is exceptionally fine.”

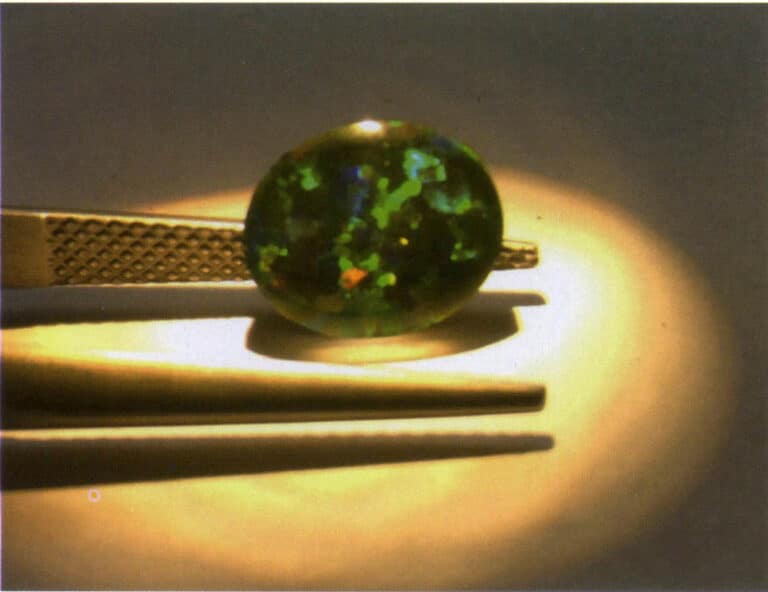

6. The Rare Kimberley Octahedral Diamond

The Kimberley Octahedral diamond (also called the Kimberley 616 diamond, Fig. 5–16) was discovered in 1974 at the Dutoitspan diamond mine in the Kimberley region of South Africa; it is a single canary yellow colored diamond. The discoverer was Abel Maretela. The rough diamond weighed 616 ct. This diamond is also the largest diamond particle produced in South Africa’s Kimberley region, its crystal form being a complete octahedron, hence the name Kimberley Octahedral diamond; because of its weight, it is also called the Kimberley 616 diamond.

This diamond is now displayed at the open-pit mine museum in Kimberley, South Africa. Because the diamond retains a complete octahedral form, its owner decided to preserve it in its original shape for public viewing in the museum.

7. The Centenary Diamond, as Rare as Morning Stars

(1) Discovery of the Centenary Diamond

The Centennial (also called Centenary) diamond was discovered on July 17, 1986, by an X-ray sorting machine on the processing line of the Premier diamond mine in South Africa, weighing 599 ct. At the time, only a few people knew of this important find; the company suppressed the news and required those informed to maintain strict confidentiality. It was not until May 11, 1988, at De Beers’ centenary celebration, that the discovery was formally announced. The diamond is of exceptional quality—white and flawless with a slight pale rose tint—extraordinarily beautiful and a rare treasure, and was named the “Centenary” diamond.

(2) Cutting of the Centenary Diamond

The rough stone resembled an irregular, angular matchbox. De Beers invited the world’s most famous diamond cutter, Gabi Tolkowsky, to evaluate and cut it. He was the inventor of the modern standard round brilliant cut and the nephew of Munsel Tolkowsky.

When he first saw the diamond, he was astonished by its clarity, considering it the cleanest diamond he had ever seen. To cut this diamond, De Beers assembled a team of veteran diamond cutters. They built a special “workshop” in the basement of the De Beers Diamond Laboratory in Johannesburg, South Africa. The first step in cutting the diamond was to remove some large fractures that connected the surface to the interior. For this, he chose the traditional hand-sawing method to avoid the heat and vibration produced by laser cutting. This work took a total of 154 days and removed about 50 ct from the rough. From the remaining rough, he designed 13 different cutting proposals and submitted them to De Beers’ board for discussion; the modified heart-shaped cut was ultimately selected. After the plan was chosen, the actual cutting of the Centennial Diamond began in March 1990 and was completed in January 1991, taking about 10 months in total.

After cutting, the diamond weighed 273.85 ct, measured 39.90mm×50.50mm×24.55mm, and had 247 facets: 75 on the crown, 89 on the pavilion, and 83 on the girdle (Fig. 5–17). Cutting so many facets on a single diamond was a first in the history of diamond cutting. In addition, two pear-shaped flawless diamonds were cut from the rough, weighing 1.47 ct and 1.14 ct respectively. The famous diamond is currently in De Beers’ collection and is estimated to be worth $100 million.

8. The Extraordinary Cullinan Heritage Diamond

Figure 5–19 The 24 finished diamonds cut and polished from the Cullinan Heritage diamond

Figure 5–20 The 104 ct round brilliant diamond

9. The Extremely Rare Baumgold II diamond

10. The Enigmatic Jacob–Victoria Diamond

(1) Discovery of the Jacob–Victoria Diamond

The Jacob–Victoria diamond, also known as the Victoria 1884 diamond, was discovered in South Africa in 1884. There are two differing views about the mine where it was found. One holds that the diamond was discovered at the De Beers mine in Kimberley, South Africa; the other believes it was found at the Jagersfontein mine in Kimberley. The rough diamond weighed 457.50 ct, its crystal was intact and octahedral in shape, its colour was bluish-white, it was pure and flawless, transparent as water, and of excellent quality. The diamond was named “Victoria 1884.”

(2) Cutting and Polishing of the Jacob–Victoria Diamond

The owner decided to send the diamond to the renowned Jacques Metz company in Amsterdam, Netherlands, for cutting and polishing, with the skilled cutter M. B. Barends specifically responsible. For this purpose, he even set up a dedicated “workshop.” First, he cut a flawed piece from the rough and polished it into one brilliant-cut finished diamond, weighting 19ct. The owner sold this diamond to the King of Portugal.

On April 9, 1887, before Queen Emma of King William III of the Netherlands, the remaining flawed piece was begun to be cut and polished, a process that took about one year in total. Ultimately, the rough was cut into an oval brilliant cut with 58 facets, weighing 184.50 ct; the diamond measured 39.50 mm long, 29.25 mm wide, and 22.50 mm thick. Its colour and clarity were excellent, and the diamond could exhibit a bluish fluorescence (Fig. 5–23).

(3) The Jacob–Victoria Diamond Transaction

After the cutting was completed, the diamond’s owner began looking for a buyer, quoting £300,000. Soon, a message arrived from Alexander Malcolm Jacob, a jeweller and antiques dealer in Simla, India, that Mahbub Ali Khan, the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, was interested in purchasing the diamond at that price. After multiple rounds of bargaining, Jacob received £150,000 from the Nizam as a down payment for the purchase. Jacob personally delivered the diamond to the ruler, who promised to pay the remainder as soon as possible. Meanwhile, British residents living in Hyderabad learned of the transaction and quickly moved to stop it to prevent the Hyderabad government from going bankrupt. With no alternative, Jacob resorted to legal action to recover the balance. Ultimately, the parties reached an out-of-court settlement: the Nizam of Hyderabad and the merchant Jacob each obtained ownership of half the diamond. Thus, the diamond became known as the Jacob–Victoria diamond.

Until 1970, descendants of the Nizam of Hyderabad planned to sell the jewellery collection, including the Jacob–Victoria diamond, at auction, but were stopped by the High Court of India. After a series of negotiations and lawsuits, in 1993, the Indian government decided to purchase all 173 pieces of the Nizam’s remaining jewellery collection as national treasures. After bargaining, the government paid approximately $70 million for the collection, of which the Jacob–Victoria diamond accounted for about $13 million.

Currently, the Jacob-Victoria diamond is valued at approximately $70 million.

11. The Dazzling De Beers Diamonds

Figure 5-25 Replica of the Patiala Necklace

(The yellow diamond at the lower part is a replica of the De Beers diamond)

After the ruling prince died, the Patiala necklace passed through many hands. In 1947, it seemed to vanish from the earth without a trace and was never seen again. Half a century later, in 1998, it reappeared in a secondhand jewellery shop in London. To everyone’s regret, the Patiala necklace had been completely altered by then. The necklace itself was partially damaged, the De Beers diamonds set in it had “disappeared,” and the seven large diamonds set in the centre were gone, leaving only five diamond-set platinum strands. Cartier’s master craftsmen were each heartbroken when they saw it.

Because the lost diamonds and gemstones were impossible to recover, Cartier’s jewellery craftsmen could only use cubic zirconia and synthetic rubies to replace the seven large diamonds and rubies that had been lost from the Patiala necklace, and the De Beers diamond that had served as the necklace’s pendant could only be replaced with cubic zirconia. Then, using its superb craftsmanship, Cartier spent four years successfully emulating the exquisite workmanship and style of craftsmen from the late 1920s, once again presenting the breathtaking “work of art” to the public. However, the restored Patiala necklace could not compare to the brilliance of the original necklace set with top-quality diamonds; people could only patiently wait for those lost treasures to “return to their rightful owner.” The Patiala may shine again.

On May 6, 1982, the De Beers diamond appeared at Sotheby’s auction house in Geneva, Switzerland, and sold for $3.16 million.

12. The Incomparable Niarchos Diamond of the Present Age

(1) The Discovery and Trade of the Niarchos Diamond

The Niarchos diamond, discovered on May 22, 1954, at the Premier diamond mine in Transvaal, South Africa, weighed 426.50 ct as a rough stone, was internally flawless, and the size of the rough was 51mm×25mm×19mm. Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, then chairman of the De Beers board, after closely examining the diamond, considered it to be the best-colored diamond he had ever seen. The diamond was named after Greek shipping magnate Niarchos Stavros Spyros, who was an art collector and investor.

The diamond was sent to London and, in January 1956, was sold by the Diamond Trading Company (DTC), a De Beers subsidiary, to the renowned American jeweller Harry Winston. The selling price was £3,000,000, which was the largest diamond DTC had negotiated in a private deal. Harry Winston sent the diamond from London to New York by ordinary registered mail, costing £1.75.

(2) Cutting of the Niarchos Diamond

The next issue to consider was how to cut this large diamond. Harry Winston and his diamond-cutting team, after several weeks of research and discussion, decided to cut the rough stone into one diamond as large as possible, believing that the historical value of a large diamond was incomparable and more meaningful than cutting it into several smaller, easily sellable stones.

Harry Winston entrusted his chief diamond cutter, Bernard de Haan, with full responsibility for cutting this diamond. De Haan came from a family of diamond cutters in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was highly skilled. He spent a long time studying devotedly, devising various cutting plans, and making several lead models of the rough stone and the envisioned finished stones before beginning the formal cutting work. First, he spent five weeks cleaving off a 70 ct rough from the original stone along its cleavage and cut it into a perfect finished olive-shaped brilliant weighing 27.62 ct. Next, he spent about five weeks removing another 70 ct rough from the original stone and cut it into an emerald-cut finished diamond weighing 39.99ct. At this point, the remaining rough weighed about 270ct, and de Haan began carefully fashioning this relatively large rough. After 58 consecutive days of arduous work, a brilliant pear-shaped diamond appeared, weighing 128.25 ct, with a total of 144 facets, 86 of which are on the girdle (Fig. 5–26). On February 27, 1957, this beautifully finished diamond appeared before the public for the first time. Cutter de Haan nicknamed it the “Ice Queen,” believing that if the diamond were placed in a bucket of ice, it would be difficult to find, which fully testified to the stone’s high colour grade and clarity. The April 1958 issue of National Geographic published an article introducing the Niarchos diamond and the entire cutting process.

Greek shipping magnate Nicholas (Neilkoss) Stathopoulos Spyros purchased the diamond from Harry Winston in 1958 for $2 million as a gift for his wife Charlotte Ford. At the same time, he also bought the finished diamonds weighing 27.62 ct and 39.99 ct that had been cut from the Neel Kous rough. Neel Kous was very generous and often lent the large diamond for exhibitions. In 1966, the Neel Kous diamond returned to its place of origin—South Africa—to participate in a grand centennial jewellery exhibition held there.

Currently, there are no public reports on the whereabouts of the Neel Kous diamond. The 39.99 ct emerald-cut diamond originating from the Neel Kous rough appeared at Sotheby’s in New York in 1991 and was purchased by Sheikh Ahmed Hassan Fitaihi of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for $1.87 million. The GIA graded the colour of this diamond as D and the clarity as VVS1. Today, this diamond is known as the “Ice Queen.”