How Can Enamel Revolutionize Your Jewelry Designs: Advantages, Techniques & Applications?

The Relationship Between Enamel and Jewellery Design

Pendant "Feuerriff"

Πίνακας περιεχομένων

Section I Advantages and Disadvantages of Enamel Technique

From the definition of enamel craft in previous article, enamel glaze and metal must fuse into one body after firing at high temperature to be called enamel; in other words, enamel depends on metal to exist. This determines the necessity of combining enamel with jewellery. Enamel itself has properties of high-temperature resistance, oxidation resistance, and long-lasting colour, and these characteristics make its combination with jewellery possible. Beyond possibility and necessity, enamel’s varied colours, brilliant lustre, and texture give it a unique position in jewellery.

In any era, enamel on jewellery is always an attractive design element. When a piece of jewellery employs enamel techniques, the viewer’s gaze is invariably drawn to it and lingers. Even those completely unfamiliar with enamel craftsmanship are amazed by its enchanting colours and gem-like shine. The reason enamel is so appealing and embodies a distinct beauty is that the enamel process itself possesses some unique and irreplaceable advantages.

(1) Enamel glaze and metal are fired together at temperatures above 700°C, bonding very firmly and resisting detachment; this is why some enamel pieces can retain the appearance they had when made centuries ago.

(2) Because the basic component of enamel glaze is silicon dioxide, similar to the basic component of glass, the fired enamel becomes glassy, resistant to acids and alkalis, and will not oxidize.

(3) After firing, the enamel surface is hard and has a glass-like lustre.

(4) Enamel glazes come in a wide range of colours—transparent, opaque, pearlescent, etc.—providing broader possibilities for jewellery design.

(5) There are many types of enamel techniques; different techniques produce different visual effects, and several techniques can be combined in a single piece to achieve richer results. Therefore, using enamel technique not only expands design possibilities but can also greatly enhance the craftsmanship value of a piece of jewellery.

The advantages mentioned above are why artists and craftsmen love to use enamel technique in their work. However, for jewellery design and production, enamel technique also has its “weak points”—that is, some drawbacks that increase production difficulty and affect the final result.

(1) Works that require firing must have all welding structures completed before the enamel technique firing. Once the enamel areas have been fired, no part of the piece may be welded with an open flame; otherwise, the fired enamel will crack or discolour. If a problem arises with a welded area after firing, it can only be repaired by laser spot welding, which itself has significant limitations; furthermore, pieces prepared for enamel firing require high-temperature soldering when welding metal structures, and the solder joints must be very secure to withstand the high temperatures during firing.

(2) The solder used in welding has a great impact on the enamel glaze. Residual solder on the metal surface can cause colour changes in the enamel glaze, create bubbles in the glaze, or even cause cracks. Figure 10-1 shows the back of a piece, where the enamel around the solder joints has turned black due to the solder’s influence. Therefore, when welding metal parts, welding techniques must be clean and tidy; no solder residue should remain on the metal surface outside the weld seam. If a small amount of solder residue is observed, it must be cleaned off with a bur before firing the enamel.

(3) The basic composition of enamel glaze is similar to that of glass, so its weight after firing is also similar to that of glass. Since both the front and back of a piece require enamel technique, this further increases the finished weight. Because jewellery is an ornament worn on the body, comfort must be considered, so the weight of enamel is an issue for jewellery. Designers need to take this into account in the design stage by reducing the enamel area or decreasing the number of enamel layers to minimize the piece’s weight.

(4) Although enamel has a relatively high surface hardness, its impact strength is very low; it is a hard and brittle material. Therefore, for jewellery designs that include enamel, the metal parts need to be protected to prevent the risk of chipping.

(5) The enamel technique process is relatively complex; the more complex the process, the longer the production time and the higher the manufacturing cost. In addition, the enamel technique process is not completely controllable, and the failure rate during production is relatively high, which further increases costs. Most importantly, the enamel technique process cannot reproduce the same colour or effect every time, so if a product requires a high degree of standardization, true mass production is difficult to achieve.

Every technique has areas where it is superior to others, as well as its weaknesses. One important purpose of studying a technique is to fully understand its strengths and weaknesses so that, in design and production, you can make full use of the technique’s advantages and avoid or mitigate potential problems. This is a process that requires long-term accumulation and repeated trial and error in practical operation, and it is also a process of accumulating very valuable experience.

Section II Ways of Combining Enamel with Metal Parts

If an artwork requires the use of enamel techniques, many process details must be considered in advance, including structure, weight, and procedures. Any small oversight can lead to a variety of problems during fabrication and production, causing waste of materials and time.

Generally speaking, the bonding of enamel to metal components can be achieved in the following ways.

(1) Firing the enamel directly onto the metal part. If a jewellery piece emphasizes the metal components, with a small enamel area serving only as an accent or decoration within the whole piece, the maker will typically choose to fire the enamel directly onto the already completed metal part, as in the work shown in Figure 10-2.

Suppose a handcrafted blank is to be enamelled later. In that case, it places higher demands on the soldering—requiring that the metal surface be completely free of remaining flux, so as not to affect the colour of the glaze, and that all joints be soldered very solidly to withstand the high temperatures above 700 degrees Celsius required for firing the enamel. If the metal body of the jewellery is produced by casting, the potential problems caused by soldering can be avoided.

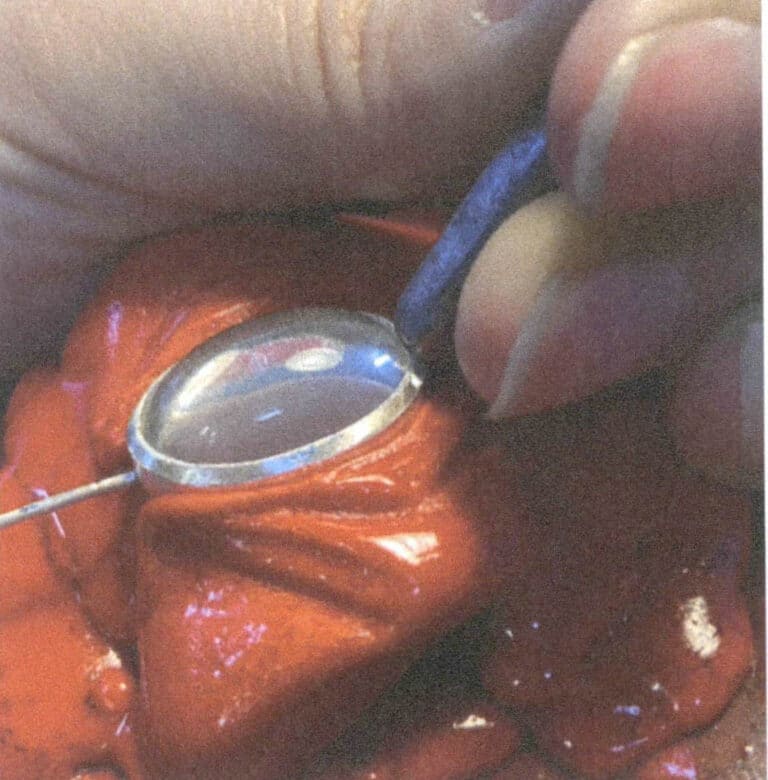

However, because cast pieces are made of alloy, various problems tend to occur during the firing of enamel. For example, metal surface blistering: the metal portion shown in Figure 10-3 developed a rough, blistered surface after a single dry-firing in the kiln. Another common problem on cast pieces is local failure of the metal to bond with the glaze; the work shown in Figure 10-4 has an area where the enamel always flakes off. Sometimes casting defects in the metal base plate cause localized discolouration of the glaze after firing or uneven enamel colour across the piece. These problems are all due to the unavoidable presence of Caused by impurities or uneven distribution of different metals.

Figure 10-3 Metal surface roughening and blistering caused by casting defects

Figure 10-4 Local enamel detachment caused by casting defects

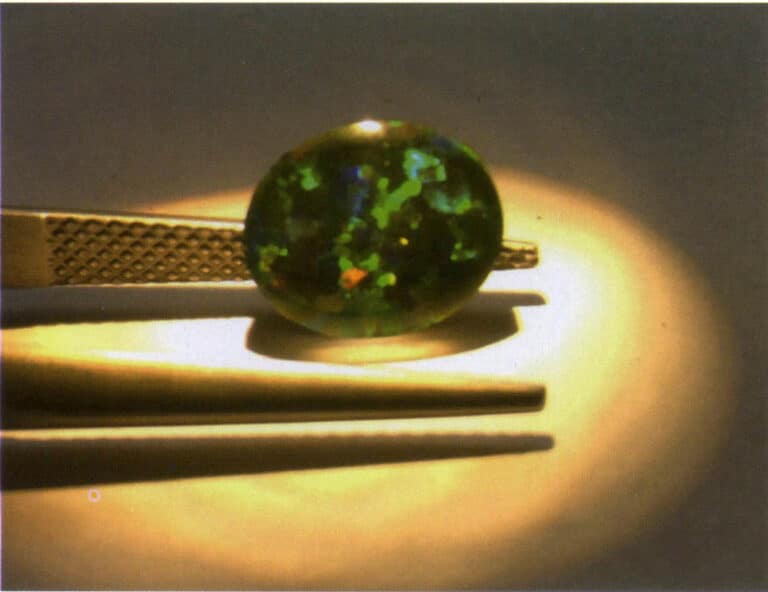

(2) Fixing the enamel parts to the metal structure by setting. Suppose an item of jewellery is primarily composed of enamel parts. In that case, it means that during production, the requirements for enamel technique must be given priority as much as possible to avoid any accidents that could affect the firing of the enamel, such as solder residue or impurities in castings. In such cases, the maker will usually fire the enamel parts separately and then set them into the main structure, effectively treating the fired enamel metal pieces as if they were gemstones. However, compared with gemstones, enamel pieces usually have larger areas and greater weight, so bezel or prong settings are typically used; techniques for setting small stones, such as bright-cut setting or gypsy setting, are not suitable for enamel.

From the above, the main methods for setting enamel are bezel setting, prong setting, and combinations of the two.

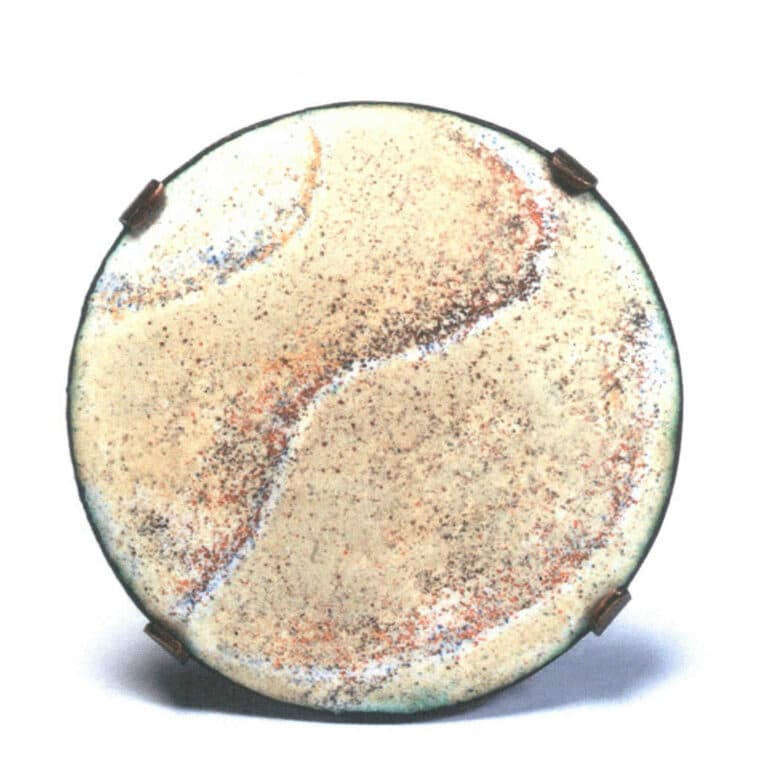

Bezel setting is the most common method for setting enamel works, because the bezel provides good protection for the enamel surface. Figure 10-5 shows a pendant by Latvian artist Sergejs Blinovs, which uses a bezel setting to secure the enamel part.

The advantage of prong settings is that they cover less of the piece, allowing the enamel work to be presented more completely. In addition, prong settings offer greater flexibility and can accommodate works of various shapes. Figure 10-6 shows a pendant by Canadian artist Aurelie Guillaumede, which uses prong settings on both the front and back to secure the enamel sections of the piece.

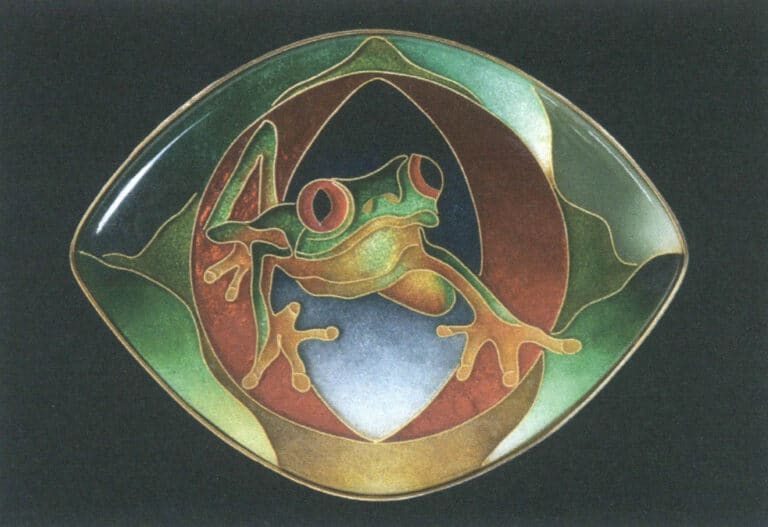

One drawback of prong settings is that they offer relatively poor protection for the enamel, so some makers combine bezel and prong settings. They saw several cuts into the bezel rim and pushed the small metal segments between the cuts inward to act as prongs; this both protects the enamel and maximizes the display of the enamel’s full appearance, making the overall form of the piece more complete. Figure 10-7 shows cloisonné enamel works by American artist Sue Szabo; the setting method used in these pieces is a combination of bezel and prong settings.

In addition to the methods mentioned above, some enamel artists use back-mounted settings to solve setting issues, placing bezels or prongs on the reverse side of the piece to ensure the front remains beautiful and intact.

Figure 10-6 Pendant

Figure 10-7 Cloisonné enamel

(3) Use rivets or screws to attach the enamel parts to the metal parts. Besides the common setting methods, rivets or screws can be used to join and secure the enamel portions to the metal parts of jewellery pieces. Both methods require leaving holes in the metal base for the rivets or screws before firing the enamel. During the firing process, take care not to let the glaze flow into the reserved holes; after firing, be very careful when riveting or screwing to avoid damaging the enamel surface. For example, in the earrings shown in Fig.10-8, the hemispherical cloisonné enamel part is connected to the main body from the back with small screws.

Section III The Application of Enamel Techniques in Jewellery

Jewellery is actually a very broad category. From a professional perspective, jewellery can be subdivided into commercial jewellery, high-end bespoke jewellery, modern art jewellery, and so on.

(1) Commercial jewellery refers specifically to pieces designed and produced with market sales and mass consumers as the target; these include both handcrafted items and factory-produced goods. Materials used are mostly gold and silver, precious or semi-precious stones, and the techniques chosen must take into account cost and profit ratios as well as suitability for mass production.

(2) High-end bespoke jewellery refers to high-end jewellery pieces custom-designed by luxury brands for private clients; the materials chosen are often costly precious metals and top-tier gemstones, and accordingly, high-end bespoke jewellery demands very high standards of craftsmanship.

(3) There is another rather special category of jewellery called “modern art jewellery.” Modern art jewellery differs from traditional notions of jewellery: its design and creation are not aimed at market sales, nor do they necessarily follow traditional aesthetic rules; instead, they emphasize the artist’s or designer’s personal expression. Compared with commercial jewellery and haute couture jewellery, modern art jewellery’s themes and materials are almost unrestricted by any rules, and comfort in wearing is not necessarily a primary consideration (this point remains controversial). Creators of modern art jewellery are often independent artists, freelance designers, or faculty and students from jewellery programs.

Among these jewellery categories, the enamel technique is most frequently used without regard to cost in high-end bespoke jewellery and modern art jewellery; for commercial jewellery, enamel technique is too expensive, yields limited profit, and is unsuitable for mass production.

The following discusses the applications of enamel technique in high-end bespoke jewellery and modern art jewellery, respectively.

1. Enamel Techniques in High-End Bespoke Jewellery

From the moment enamel techniques were born, they have been rare and expensive processes, unsuitable for mass production and jewellery aimed at popular consumption — the technical characteristics of enamel itself determine this.

Chinese cloisonné pieces in our country are an exception: from the founding of the People’s Republic until the 1990s, they briefly achieved mass production and relatively affordable prices. However, that approach also led to designs and manufacturing no longer being fully controlled by skilled artisans, allowing some coarse, inferior products to enter the market and causing our cloisonné industry to fall into a low ebb after the 1990s. With recent national emphasis on preserving intangible cultural heritage, some traditional craftsmen have begun to readjust the market positioning of cloisonné, rediscover and organise traditional techniques, and optimise design and craftsmanship to restore cloisonné’s artisanal status. As a result, some excellent cloisonné brands and high-quality cloisonné products have gradually reemerged in recent years.

Currently, most cloisonné products in our country are large decorative pieces; high-temperature enamel items in the jewellery field are relatively rare. The enamel jewellery that we often see showcasing charming enamel work tends to be museum pieces or limited-edition designs released by top jewellery brands.

Below are some well-known enamel pieces from high-end jewellery brands.

Van Cleef & Arpels’ Lady Arpels Ballerine Enchantée watch (see images on Van Cleef & Arpels China official website enamel page) uses K white gold and guilloche enamel techniques. The background employs guilloche enamel to create textured patterns on a K white gold base, then transparent blue-purple enamel is fired, producing rich, textured, reflective effects. The fairy’s dress uses the champlevé enamel technique.

Tiffany & Co. (Schulmberger) ‘s Croisillon white enamel bangle (see images on Tiffany Co.’s official website, Tiffany & Co. Schulmberger collection) is fired with white enamel on 18K gold. This enamel bangle series was first launched in 1962, designed by Jean Schulmberger, using 18K gold, diamonds, and enamel techniques. Jean Schulmberger favoured lively natural motifs such as marine life, plants, fish, and birds, making enamel—well-suited to depict these themes—a technique he frequently used.

Patek Philippe’s enamel pocket watches often use painted enamel on both the case and the dial—that is, a painted enamel motif on the dial and a different motif on the case. Patek Philippe’s painted enamel decorations on pocket watches are exquisitely rendered, richly detailed, and delicately harmonized in colour. On Patek Philippe’s official website in China, there is a page called “Rare Handcrafts Collection” that includes a dedicated enamel section where you can see pocket watches decorated with painted enamel.

Figure 10-9 shows an enamel ring produced by the Russian jewellery brand Ilgiz F. The brand was founded in 1992 by Russian jeweller Ilgiz Fazulzyanov. Ilgiz Fazulzyanov is personally involved in every stage from design to production; he is skilled in using multiple enamel techniques in his pieces and adept at combining various metalworking methods.

For example, in the enamel ring shown in Figure 10-10, several enamel techniques were used according to the design requirements, including champlevé enamel, plique-à-jour enamel, and painted enamel. These techniques are blended extremely naturally, with no sense of being overdone. Ilgiz F.’s works perfectly combine ultimate formal beauty, intricate structure, and superb craftsmanship, demonstrating the designer’s exceptional control.

Enamel techniques on high-end bespoke jewellery often become the highlight of the entire piece. Enamel, with its irreplaceable colours and textures and its unique artistic quality, is a favoured technique of many designers. With it, designers can more freely express preferred subjects, shape distinctive design styles, and bring a fresh, romantic air to traditional, rule-bound high-end bespoke jewellery.

Figure 10-9 Enamel ring produced by Ilgiz F.

Figure 10-10 Enamel ring produced produced by Ilgiz F

2. Enameling Techniques in Modern Art Jewelry

Modern art jewellery differs from traditional jewellery in that it focuses primarily on the self-expression of the artist or designer. The precious metals and gemstones commonly used in traditional jewellery impose many limitations on design and are insufficient to fully convey designers’ subtle, complex emotions; they are also less suitable for narrative or situational storytelling and often restrict creative freedom. Enamel technique, however, offers great plasticity and creative freedom, and finished pieces have ideal strength and durability, making it well-suited for creating modern art jewellery. Moreover, modern art jewellery is often created as unique pieces rather than mass-produced, which aligns with the fact that enamel technique cannot reproduce the same colour or effect every time. Because modern art jewellery is typically one-of-a-kind, the relatively high cost of enamel technique becomes acceptable. Therefore, enamel technique is a technique often adopted in the field of modern art jewellery.

Artists who work freely with enamel technique can generally be divided into two types: traditional and avant-garde experimental. Traditional artists focus more on using classical enamel techniques, striving to fully showcase the excellence of enamel glazes and the enamel technique craft in their works; their visual style tends toward the aesthetic, and the overall style of their jewellery leans closer to traditional jewellery. Avant-garde experimental artists, by contrast, make works that are more modern in form and structure. They are not satisfied with traditional materials and techniques, nor do they solely prioritize beauty and wearability; instead, they place greater emphasis on conveying concepts. The enamel technique in their works often cleverly exploits the unpredictability, contingency, and experimental nature of the enamel technique process, even using some flaws that occur during traditional firing to achieve very special effects. Thus, the presentation of enamel technique in their pieces differs greatly from that in traditional jewellery: creators no longer concentrate solely on firing the enamel to the most complete, perfect state, but retain many accidental and playful special effects, including unusual colour effects and unique surface textures, thereby expanding the expressive capacity of enamel technique.

The following artists belong to the traditional type. For many years, they have focused on creating cloisonné enamel jewellery. These artists share the common trait of being extremely skilled in craftsmanship, adept at accurately controlling the colours of glazes, and attentive to the perfect presentation of the enamel itself.

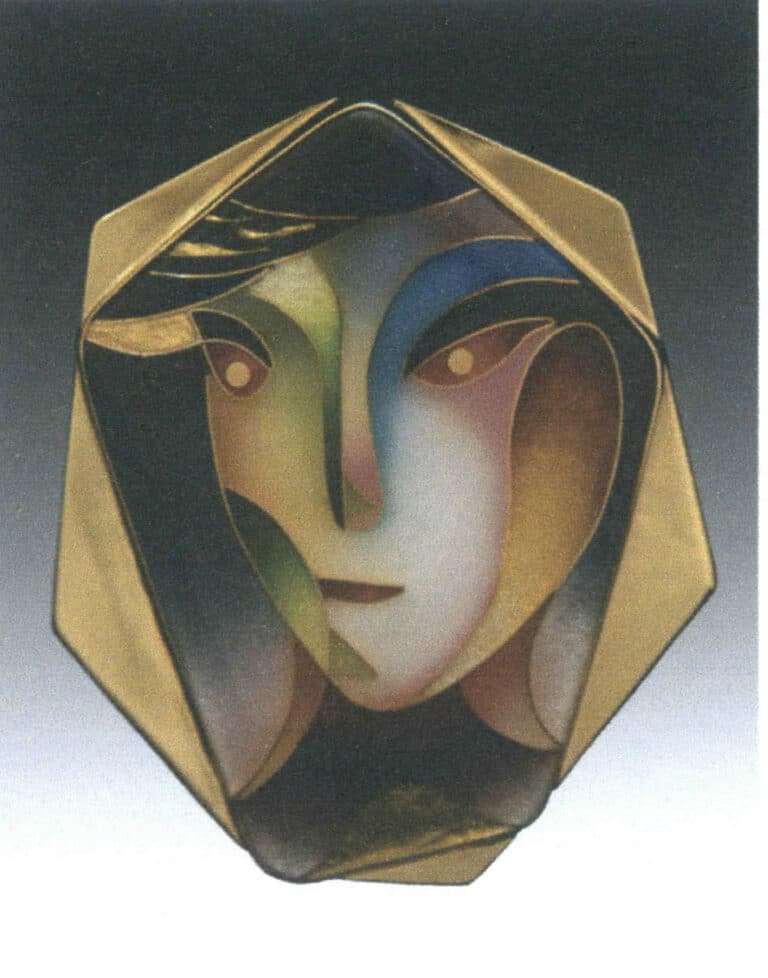

Don Viehman is an American enameler. Since he began experimenting with cloisonné in 1979, he has made it his primary creative direction and invested great passion in it. Don Viehman’s works are generally made by creating designs in 24K gold on a sterling silver base, then filling them with transparent and semi-transparent glazes. By using gradients between different colours and repeatedly layering multiple thin coats of glaze, he creates rich colour relationships and wondrous light-and-shadow effects. Don Viehman is particularly skilled at producing smooth transitions between colours, creating a sense of spatial depth through contrasts of light and dark, and of light and shadow. Figures 10–11 show one of his cloisonné enamel decorative wall hangings; this piece makes that sense of space very apparent. Figure 10–12 shows a cloisonné enamel brooch; from this work, we can see how Don Viehman uses colour gradation to handle the complex structures of a human face.

Figure 10-11 Cloisonné Enamel Decorative Wall Hanging

Figure 10-12 Cloisonné Enamel Brooch

Copywrite @ Sobling.Jewelry - Κατασκευαστής προσαρμοσμένων κοσμημάτων, εργοστάσιο κοσμημάτων OEM και ODM

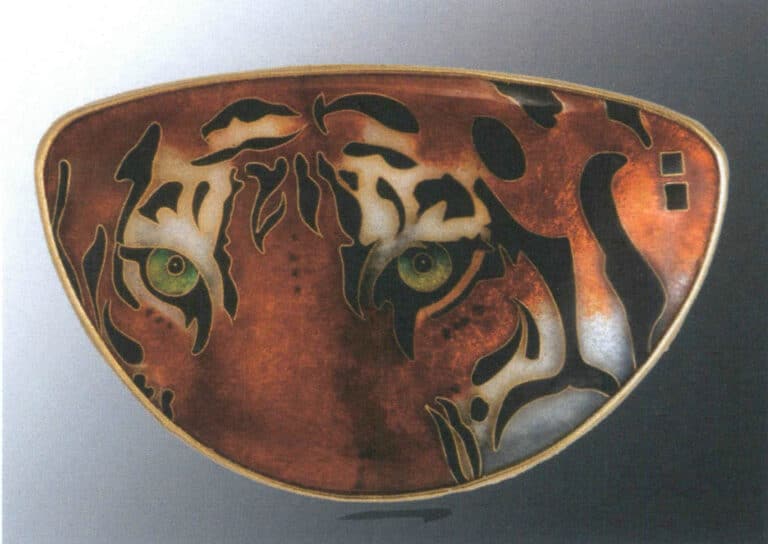

She is also very skilled with reds and blacks. For example, in the brooch shown in Figure 10–14, the image is a close-up of a tiger’s head, with nearly three-quarters of the area filled with rich, saturated red tones, accented by black stripes and white fur, creating contrasts of sparse and dense, simple and complex—realistic yet artistic.

Beyond her confident command of enamel techniques, Merry-Lee Rae pays great attention to the overall aesthetic of a piece. In the pendant titled “New Octopus” shown in Figure 10–15, the central motif is an octopus waving its tentacles, rendered in subtly shifting purples; the metal support beneath the pendant is formed from curved lines, one of which is treated as an octopus tentacle extending outward from the main form; a garnet set below the pendant echoes the colors of the central motif. The whole work feels cohesive, as if breathing gently to a shared rhythm.

Figure 10-14 Brooch

Figure 10-15 Pendant "New Octopus"

Jean Francois Dehays is an enamel artist currently living in Limoges, France, who has worked professionally in enamel technique for many years and once served as president of the Limoges Enamel Handcraft Association. His works display various enamel techniques, such as champlevé, basse-taille, and cloisonné enamel. Figure 10–18 shows a champlevé enamel decorative panel by Jean Francois Dehays, depicting hunters hunting a wild boar in a forest. This decorative panel uses the etching champlevé technique, with bright colours and strong contrasts, and the image exudes an innocent and simple atmosphere.

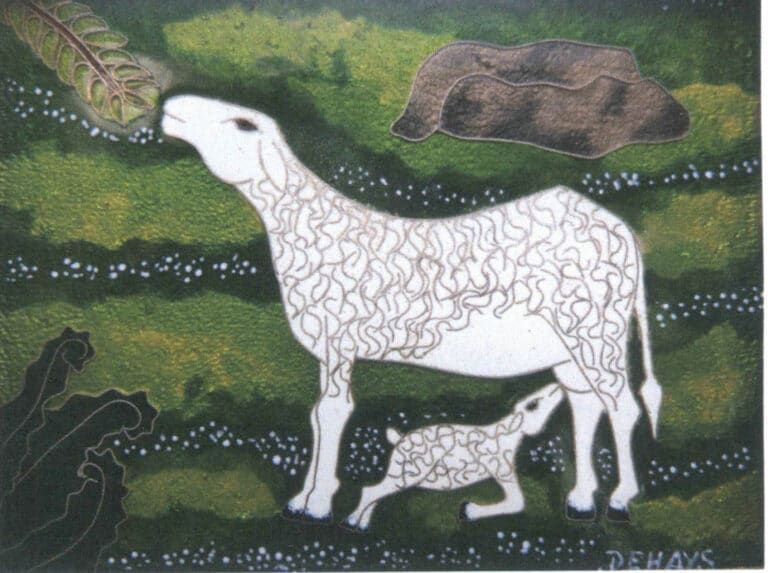

Jean Francois Dehays greatly enjoys creating small enamel panels that reflect everyday life; Figure 10–19 is another cloisonné enamel decorative panel he created, also depicting a scene from rural life. The image shows a common scene in the French countryside—sheep on the grass. In this enamel painting, he uses cloisonné and basse-taille techniques: the grass area is textured in the metal base first and then fired with transparent enamels to create a mottled effect on the turf, and irregularly bent short wires are used to form the sheep’s wool, both realistic and decorative. Compared to the artists introduced earlier, Jean-François Dehays’s creative approach is freer and more robust, which is related to his long-term life in the countryside; his works convey the leisure and joy of rural French life.

Figure 10–18 Champlevé Enamel Decorative Painting

Figure 10–19 Cloisonné Enamel Decorative Painting

British enamel artist Ruth Ball often uses cloisonné and basse-taille enamel techniques in her work. Her pieces include jewellery, tableware, wall hangings, and vases—display-oriented artworks inspired by her observations and feelings about life. Whether in form, colour, or symbolic elements within the works, they can all be traced back to the emotions that the external world evokes within the artist. Without exception, her works adopt extremely simple external outlines, contrasted by richly treated surface textures and the enamel’s understated colours.

Figures 10–21 and 10–22 show works from her “Coastline” series—”Midnight and Mist” and “Long Pebble.” In this series, she hand-carves delicate, dense textures into silver plates to mimic the natural striations on shells, then overlays them with blue-purple glazes that transition uniformly from deep to light. The effect is restrained and thought-provoking, as the artist Ruth Ball herself says: “Small things become precious because of unique memories and emotions, just as superb craftsmanship and clever design give simply shaped works an immeasurable value.”

Figure 10–21 "Coastline" series "Midnight and Mist"

Figure 10–22 "Coastline" series "Long Pebble"

Figure 10–23 City X

Figure 10–24 Winter Pendant

The artists introduced above are all internationally renowned enamellers who have been creating enamel works for a long time. They refer to their pieces as modern art enamel to distinguish them from enamels made entirely following traditional methods, but in fact, their practice still strictly follows traditional enamel techniques, with technical perfection as an important goal.

Among independent enamel artists, there are also those eager to try new directions, whom we can call avant-garde experimentalists. The enamel techniques used in these artists’ works, both in method and presentation, differ greatly from traditional enamel craft. The works take freer forms and present a lighter, more relaxed effect. From the works, it is clear that these artists pursue the variety and serendipity of enamel; the relationship between enamel and metal, and contrasts between enamel and other materials, are elements they like to exploit. In these pieces, the improvisational approach of modern art jewellery, its originality, and the unpredictability of enamel techniques meet, producing interesting and refreshing collisions.

Spanish jewellery artist Montserrat Lacomba studied and worked as an illustrator early in her career, so her work is strongly painterly; her subjects are often impressions of landscapes or inspired by family photographs. Her works emphasize inner expression, frequently using the special effects of enamel techniques to achieve intense colours and unique textures. The brooch shown in Fig. 10-25 is from her “In the Waves” series; this series uses the dry-sieving technique in enamel technique, sprinkling dry enamel powder over a copper base to create an effect like waves washing a beach.

Fig. 10-26 shows another of her series — a brooch from the “12 Moments in Life” series, which reflects memories of the twelve months of a year. The artist drew inspiration from old photographs and used enamel techniques to achieve painterly effects, marking particular feelings and experiences in life. Montserrat hopes to convey her emotions toward nature, landscape, and loved ones through this series. What Montserrat expresses through enamel is not only her observation of things but also her inner emotions and feelings. Thus, enamel is not limited to depicting an image; it can achieve broader, deeper expression.

Figure 10-25 Brooch from the "In the Waves" series

Figure 10-26 Brooch from the "12 Moments in Life" series

Jewellery artist Nicole Beck, now living in Munich, Germany, studied jewellery design in Germany and once apprenticed with Professor Otto Kunzli. Her works are extremely minimal in form and often use enamel techniques, but they rarely display the bright colours typical of traditional enamel technique. She often etches uneven textures or patterns onto the surface of her pieces, fires a thin layer of enamel over them, and then polishes. The enamel on the raised areas is partially abraded away to reveal the metal base, while the enamel in the recessed areas is preserved. In this way, on the surface of the work, the remaining enamel contrasts interestingly with the abraded, exposed metal—contrasts in surface texture as well as in colour and lustre. Most intriguing is that this special surface effect arises randomly during the making process and involves a great deal of chance. Even the artist cannot control their boundaries, size, or shape with absolute certainty. Figure 10–27 shows a brooch titled “One” from her “Dear Stranger” series; after polishing, the remaining enamel in the checkered recesses forms irregular, nearly diamond-shaped patterns, and on close inspection, the abraded enamel layers reveal subtle and varied stratifications and effects.

Figure 10–28 shows a brooch titled “Portrait” from Nicole Beck’s “What Was Preserved” series; the exposed pinholes can be clearly seen on the polished white glaze surface. For traditional enamel technique, such pinholes would unquestionably be considered defects, but in this piece, they become part of the work’s subtle tonality and are indispensable to it. The artist cleverly makes use of the uncertainties inherent in the enamel technique process to give her work a unique surface texture and colouration.

Figure 10-27 “Dear Stranger,” series brooch “One”

Figure 10-28 "What Was Preserved" series brooch "Portrait"

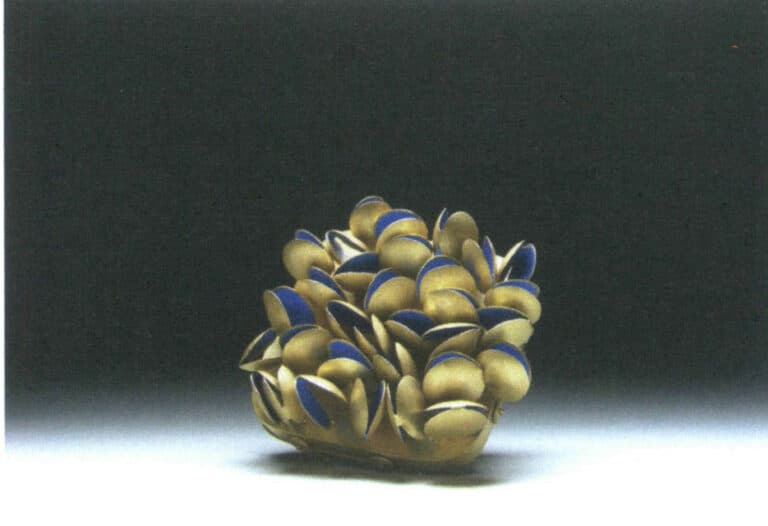

British jewellery designer Jacqueline Ryan’s works most often feature a single element repeated rhythmically throughout the piece, expressing the artist’s perception of nature and an abstracted refinement of that perception. Jacqueline Ryan says she is deeply fascinated by the ancient arts’ reverence for and love of nature, and hopes to achieve a timeless, singular, and original aesthetic through the arrangement of simple elements and flawless craftsmanship. All of her works use gold as the primary material, with simple opaque glazes fired onto the metal—such as white, cobalt blue, and turquoise—revealing both her mastery as a goldsmith and an artistic language that is extremely concise and pure. From these pieces, one can indeed sense the same ancient, mysterious quietude found in ancient Egyptian or Etruscan art. The brooch shown in Figure 10–30 imitates organic forms and structures from nature: several flower-like elements combine to form an irregular circular brooch. Each floral element is constructed from simple linear shapes, abstracted and distilled; the enamel is fired in the centres of the flowers, and it is a blue-green of somewhat low saturation. The work’s creative inspiration indeed comes from nature, but the entire piece is the artist’s refinement and re-presentation of nature, carrying strong subjectivity.

The brooch shown in Figure 10–31 is composed of many small shell-shaped elements with the inner surfaces fired with opaque cobalt-blue glaze. The numerous shell-shaped components face different directions, like marine creatures drifting with the currents, while simultaneously being arranged within a regular square frame. All of Jaqueline Ryan’s works are a direct response to nature combined with her design thinking—that is, a perfect union of feeling and thought. Jacqueline Ryan’s pieces show us another possibility: using the enamel technique need not be limited to vivid colouration or dazzling effects; enamel can also be used for a simple, restrained expression, as in Jaqueline Ryan’s work. Even using only a single colour, once the precise form is found, a work can possess a powerful impact.

Figure 10–30 Brooch

Figure 10–31 Brooch

Nora Kovats is a jewellery artist from South Africa. Perhaps because she is both a jewellery artist and an illustrator, Nora Kovats is very fond of enamel work, known for its colours; almost all of her pieces use enamel. Her jewellery is clearly painterly in its creation: forms are free, colours are rich and abundant. One can clearly feel that the creator treats jewellery as a vehicle for freely expressing the spirit, with enamel acting as the paint when she paints. The plants she loves, ingredients on the kitchen counter, and fleeting beautiful moments in life can all be recreated through the enamel glaze concentrated on the pieces — not reproducing a scene or an image, but a mood or a feeling.

The necklace “Feuerriff” shown in Figure 10–32 uses red and orange enamel glazes fired onto copper pieces shaped like plant forms — like leaves, or flowers, or fruits. Combined with warm-toned gemstones such as agate, chalcedony, and rubies, it brings a sense of warmth.

Figure 10–33 shows another necklace of hers, “Creatures of the Tidal Pool,” which is similar in style to the necklace above but evokes a completely different feeling. This piece has black glaze fired onto a copper base; the glaze surface is uneven, sparsely dotted with tiny fragments of opaque blue glaze, and set with uncut black tourmaline. The silver backing is antiqued to an even black. The dark tones and carefully treated details seem to display a gathering of strength in cold, dim places.

Figure 10-32 Pendant "Feuerriff"

Figure 10-33 Necklace "Creatures of the Tidal Pool"