What Are the Incredible True Stories Behind the World's Most Famous Diamonds?

Famous Diamonds History: Koh-i-Noor, Hope, Sancy, Orloff, Tiffany Diamond Stories

Úvod:

Dive into the captivating histories of legendary diamonds that have shaped empires and ignited passions for centuries. This article uncovers the true stories behind gems like the Koh-i-Noor, the Hope Diamond, and the Sancy. Discover their origins in Indian mines like Golconda, their journeys through royal courts, and the famous rulers who owned them. Learn about their recutting, unique gemological characteristics, and how they were set into iconic crowns and jewelry. For jewelry professionals, designers, and brands, this knowledge offers invaluable inspiration and a deep connection to the most celebrated gemstones in history.

Jewellery featuring the Hope Diamond designed and made by Cartier

Obsah

Section I The Long-Suffering Koh-i-Noor Diamond

(1) Origin of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

The rough Koh-i-Noor, walnut-shaped, was mined in the Kollur mine area of Golconda, India. The diamond deposits from this district occur in alluvial deposits. Many famous diamonds were discovered here, such as the Great Mogul and the French Blue. The Krishna River cuts a large gorge at Kollur; in the 16th–17th centuries, thousands of miners panned the sands here in search of treasure. Diamonds unearthed by the miners belonged to the local rulers and were taken to Golconda for trade.

India is the earliest country known to mine diamonds, and many historically famous stones are known to have come from India. According to documentary records, one of the more reliably documented stones is the Koh-i-Noor, which the rulers of the Mughal dynasty in India once owned. Thereafter, countless bloody massacres and conflicts were provoked over this diamond. Many monarchs who once possessed it ultimately met ill fates.

(2) The Mughal Dynasty and the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

In the 16th century, the Mongol Babar founded the Mughal Dynasty in India, and from then on, the Mughal Dynasty formed an inseparable bond with the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Babar became the first monarch to possess the Koh-i-Noor. It is said that the value of this diamond could provide “one day’s food for all the people in the world” at that time. After Babar’s death, his son Humayun succeeded him. At that time, the Koh-i-Noor naturally passed into Humayun’s hands. King Akbar governed effectively and is considered the true founder of the Mughal Dynasty.

Akbar’s son Jahangir succeeded to the throne and, on an inspired whim, decided to create a treasure he named the Peacock Throne, the most celebrated treasure of the Mughal Dynasty. The throne was set with many fine gems and pearls and symbolized the power of the Mughal rulers. It is said that the Koh-i-Noor was once mounted on the Peacock Throne. The throne took decades to make and was not completed until Shah Jahan, Jahangir’s son, came to the throne.

At the end of Shah Jahan’s reign, the king fell gravely ill, and his heirs were engaged in a brutal struggle for the throne. In that process, Shah Jahan’s third son, Aurangzeb, prevailed, winning the Mughal throne and becoming the sixth Mughal emperor. At that time, his father Shah Jahan was seriously ill, but was imprisoned by him in the fortress on the banks of the Jumna at Agra.

In 1665, under Aurangzeb’s rule, the famous French jeweller and traveller Tavernier was invited to observe, measure, and describe many of the gems in the Mughal treasury. However, Tavernier did not see the Koh-i-Noor in the Mughal treasury, which can be understood to mean that the Koh-i-Noor had not yet been incorporated into the treasures under Aurangzeb’s control. That conclusion is reasonable, because when Tavernier visited, Aurangzeb’s father Shah Jahan was still in captivity and still possessed many gems; perhaps it was only after he died in 1666 that the Koh-i-Noor truly came into Aurangzeb’s hands.

(3) Nadir Shah and the Koh-i-Noor

Nadir Shah was the founder of Persia’s Afsharid dynasty. After ascending the throne in 1736, years of warfare left the treasury empty, and Nadir decided to send his forces to plunder the riches of the Mughal Empire. In 1739, the Persian army led by Nadir occupied India and then quelled various uprisings with bloody massacres, proclaiming “the Sultan of sultans, the King of kings is Nadir.” Countless and priceless treasures were taken from the Mughals. Nadir was especially fond of the Peacock Throne because it symbolized the supreme power of the Mughal kings. Thus, the Mughal Empire’s most precious Peacock Throne was seized by Nadir. Among the spoils was the Koh-i-Noor; when Nadir saw the diamond, he could not help exclaiming “Koh-i-Noor” (meaning Mountain of Light). That name thus became recorded in the annals of diamond history.

After plundering countless treasures from the Mughal dynasty, Nader returned to Persia with the Koh-i-Noor diamond. On the surface, this conquest of India was very successful, and he obtained what he wanted most, but this also planted the seeds for Nader’s downfall. Due to years of continuous warfare, he developed oedema and gradually grew extremely arrogant; in the later years of his rule, he became one of the most notorious tyrants in history. In 1747, Nader was murdered in his tent in Khorasan.

(4) The Struggle for Power Sparked by the Koh-i-Noor

After Nader’s death, the Koh-i-Noor diamond fell into the hands of the founder of the Afghan Durrani dynasty — Ahmed Shah Abdali — who had been Nader’s closest and most loyal officer. He led the retreating Afghan soldiers back to Afghanistan, and Ahmed’s forces were the first to take control and unify Afghanistan.

Because of the immense allure of the Koh-i-Noor, although the diamond had by then come into Ahmed’s possession in Afghanistan, violent attempts to seize it continued relentlessly. Later, as civil war again broke out in Persia, Agha Muhammad Khan came to power. He was a eunuch — castrated at age five by Nader’s successor — and was fanatically obsessed with power and jewels; his greed for them knew no bounds.

Agha Muhammad led forces to seize eight provinces of Persia and declared himself king. His first target was to plunder the treasures once possessed by Rukn. He employed various cruel tortures to force Rukn to reveal the hiding places of his treasures and gradually obtained some. But what he cared about most and most desired was the Koh-i-Noor; he refused to believe that Rukn no longer possessed it. Having failed to get the treasure he wanted, Agha, furious and humiliated, ordered Rukn bound to a chair and placed a “crown” made of thick, wet clay on his head. In a brutally cruel “coronation,” Agha personally poured a pot of molten lead into the “crown,” and Rukn died.

Ahmed Shah also set his sights on the wealth of India, invading India eight times. In 1772, he abdicated in favour of his son Timur, who thus inherited all the treasures of Afghanistan’s treasury, which would have included the Koh-i-Noor.

After Timur’s death, his son Zaman successfully ascended to the throne. Following the example of his predecessors and their established mode of rule, he captured several cities of the time and ruled for seven years.

Upon his return from a military campaign in India, his half-brother Mahmud seized the throne, deposed him, cruelly gouged out his eyes, and imprisoned him within the palace. Perhaps Zaman had a premonition of what was to come; although he had no time to escape, he managed to bury some of the jewels he carried with him in a hole dug with his sword and hid the Koh-i-Noor diamond in a crack in the wall. Due to Zaman’s deliberate arrangements, Mahmud ultimately failed to obtain the Koh-i-Noor. In 1803, Mahmud also lost his throne, deposed by his younger brother, Shuja. Shuja’s fondness for jewels – especially the Koh-i-Noor diamond – far exceeded his passion for power. Shuja also intended to follow court tradition by blinding the deposed King Mahmud. Although many high-ranking nobles at court pleaded for mercy, it seemed futile. Only when the blinded former king Zaman supported their pleas by offering the hiding place of the Koh-i-Noor diamond was the request granted. Thus, Mahmud narrowly escaped blindness, but he remained imprisoned, while Shuja obtained the long-coveted Koh-i-Noor diamond.

While the various Afghan kings were engaged in repeated battles with their enemies, the British were gradually expanding their influence in India through trade with the British East India Company. Through diplomacy and persistent pressure, the British Royal Government gradually legitimized the presence of the British army in India. However, when Shuja returned to Kabul from a military expedition, he found that his brother Mahmud had successfully escaped from the prison where he had been held for six years, gathered forces, and regained power for the second time. Upon seizing power, Mahmud immediately exiled his brother Zaman. While passing through Sikh-controlled territories, Zaman sought refuge with the Sikh leader, Ranjit Singh. This historical shift set the stage for the change in ownership of the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

(5) The Koh-i-Noor Diamond Returned to India Once Again

Ranjit Singh, known as “the Lion of Lahore,” was the son of a Sikh sect leader. He was resourceful, brave in battle, and especially skilled at horseback archery. Although short in stature and blind in one eye, he was resolute and possessed considerable leadership ability. Using the power he held, he gathered the scattered Sikhs together. By the age of 17, he had full control of the Sikh tribes and had effectively become their leader. Employing flexible and varied tactics, he easily conquered vast territories, including the central city of Lahore. At 18, he declared himself the head of Lahore, and in 1801, founded the Sikh Empire, becoming its first ruler. At this point, the greatest threat to the Sikhs was no longer the Mughal dynasty but the British. The British already controlled all of India except Punjab. Ranjit Singh adopted a pragmatic strategy, allying with the British rather than making enemies of them. During this period, he even had the British train his troops, develop his armed forces, and further expand his power.

After Muhammad regained power a second time, he began a campaign against Suga. Although Suga organized several resistance movements, they all failed. In 1812, Suga was captured by another force and detained in Kashmir in northern India. When Zaman heard the news, he sought assistance from his master, Ranjit Singh, to rescue the imprisoned Suga. Ranjit Singh accepted the proposal, but the “payment” for this rescue was the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Ranjit Singh, with a strong sense of self-preservation, dispatched troops to attack Kashmir, freed Suga, and brought him back to Lahore.

When Sujia heard that the “reward” for his rescue was to hand over the Diamond of the Mountain of Light, he was extremely unwilling and repeatedly claimed he no longer possessed the diamond. Secretly, however, he intended to quietly send it back to Kabul to raise funds and secretly organize an army to try to make a comeback. He concocted various lies to evade the issue: first, he said the diamond had already been pawned; second, he said the diamond had been lost along with some other jewels; third, he said some large colourless topazes were being passed off as diamonds, which Ranajit Singh’s court jeweller disproved. At this point, Ranajit was very angry and again threatened to cut off food and drinking water, forcing Sujia to hand over the Koh-i-Noor Diamond as soon as possible. Although Sujia was extremely reluctant, he had no choice.

June 1, 1813, was the final deadline agreed upon by both parties for handing over the Koh-i-Noor Diamond. The two met as arranged, sitting cross-legged facing each other, and Sujia reluctantly handed over a small cloth pouch containing the diamond. Ranajit Singh was very excited and, without hesitation, grabbed the pouch. Thus, after decades, the diamond once again returned to its country of origin—India.

Ranajit Singh set the Koh-i-Noor Diamond into a bracelet or used it as an ornament on a turban. For a time, he even set the diamond on the flank of a horse, giving his mount an extra “eye”; the uses of the diamond were extremely ostentatious and extravagant.

(6) The Recovered and then Lost Koh-i-Noor Diamond

In 1838, a group of British diplomats visited Lahore to meet with Ranjit Singh. William Osborne was one of those visiting diplomats; he was the military secretary to the British Governor-General in India. He described: “The strongman of Lahore sat cross-legged on a golden chair, wearing a thin white garment without ornamentation, but with a row of large pearls tied at his waist, and the Koh-i-Noor diamond, symbol of the mountain of light, worn on his arm.” Later, Osborne was permitted to hold the Koh-i-Noor diamond for inspection, and he further described: “This diamond must be the most beautiful, 3.81 cm long, over 2.54 cm wide, and rising 1.27 cm above the mount; egg-shaped, set in a bracelet, with a diamond on each side about half the size of the Koh-i-Noor. The diamond has no flaws of any kind.”

After Ranjit Singh’s death, Duleep Singh succeeded as ruler of the Sikh state; he was still a child, and his mother was appointed Regentrégent. Between 1848 and 1849, the Second Sikh War broke out between the British and the Sikhs, and the British were victorious. In 1849, Lord Dalhousie, then Governor-General of India, signed documents of submission to British rule with the Regentrégent and Duleep Singh. Dalhousie recorded: “…to deliver the Koh-i-Noor diamond to the Queen of England…” The British guaranteed Duleep Singh’s pension, titles, and status. Thus, the Koh-i-Noor, which had only recently returned to India, was lost again and once more left its producing country, bound for Britain.

(7) The Koh-i-Noor Diamond Is Sent to Britain

The British obtained the Koh-i-Noor diamond, but transporting this diamond back to Britain was fraught with thorns. Given the transportation conditions of the time, from Lahore to Britain, the diamond had to be carried overland to Bombay first, and then shipped from Bombay to Britain by sea.

How to transport the diamond from Lahore overland safely to the western Indian port city of Bombay was the first problem to be solved. On that long overland route, the means of transport relied mainly on horses and four-wheeled carts, and moreover, on that lengthy north-to-south journey, they often had to pass through combat zones, which shows how difficult the transport was. This problem could only be resolved personally by Governor Dalhousie, who would assume the risk of transportation. With the help of his military aide, Captain Ramsay, Dalhousie sewed the Koh-i-Noor diamond into a ribbon that was tied around his waist and also fastened by a chain around his neck, creating a “double safeguard” to prevent loss during transit. Although Dalhousie was full of confidence, he also fully understood the risk and responsibility he bore; he recorded: “In terror I understood my responsibility; when I placed the Koh-i-Noor diamond in Bombay’s treasure house, it was the happiest moment of my life.”

After arriving in Bombay, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was placed in an iron box and locked. That iron box was then placed inside a larger sealed chest and locked again. Different people held the keys, and the sealed chest was loaded onto the Royal Navy steam-sloop Medea. The captain was Naval Lieutenant Colonel Lockyer. On April 6, 1850, the Medea set sail from Bombay bound for Britain.

The voyage was full of hazards. Only a day after leaving Bombay, cholera broke out on board, and two crew members died. Captain Lockyer decided to continue toward his destination, and after crossing the Indian Ocean, he reached the French-controlled island nation in southern Africa—Mauritius. By then, the ship’s provisions were nearly exhausted, and the captain was eager to stop here to rest and to obtain adequate food supplies for the remainder of the voyage. But the signal flags from shore instructed the Medea to undergo quarantine, and two days later, they threatened that unless the ship departed immediately, it would be burned. Reluctantly, Captain Lockyer obeyed and continued toward Britain without receiving any food supplies. Misfortunes continued to follow: before reaching the Cape of Good Hope, the ship encountered a great storm; the gale tore away the Medea’s rigging and most of its fittings, and the mast was nearly snapped. By then, however, the cholera on board had been largely brought under control; upon reaching the Cape, “The Medea” received all necessary supplies such as food and fuel.

After leaving the Cape of Good Hope, the voyage of “Medea” became very smooth. The boilers were full of steam, which increased the speed of the sailing ship. From Spithead it sailed and reached the naval base in the Solent on June 29, 1850, taking only 40 days — setting a record at the time for a single-masted sailing ship on that route.

(8) Queen Victoria and the Koh-i-Noor Diamond

After the Koh-i-Noor arrived in Britain, many articles and commentaries appeared in the newspapers, arousing great public interest. Soon Queen Victoria wore this historic diamond that symbolized honour and status. The Koh-i-Noor attracted considerable attention in Parliament and among the public. People hurried to tell one another, eager for a glimpse of the famous gem. Prince Albert then had an idea: could a grand exhibition be held in Hyde Park to display the diamond to the public? Although there were many difficulties, Prince Albert was persistent, and the plan for the exhibition was finally approved. The venue chosen was a huge new building in Hyde Park — the Crystal Palace.

One of the main exhibits of the exhibition was the Koh-i-Noor diamond. The diamond was displayed in a gilded iron box and, over a period of five and a half months, attracted nearly six million visitors—about one third of the total British population at the time—many of whom came from abroad.

Visitors saw this famous historical diamond with their own eyes. Still, it was not “radiant” as some journalists who had not seen it described, so that the gap between reality and imagination was large, and the diamond’s condition disappointed many visitors. The reason was that the diamond had not been cut to optimal proportions and did not adequately display its clarity and intrinsic properties. Therefore, a bold proposal was made: could the best diamond cutters in Europe be invited to recut the stone so as to maximize the diamond’s inherent beauty? Doing so would reduce the diamond’s size and weight, but its market price would increase greatly, and it might become one of the finest diamonds in Europe or even the world. Although this course of action had its advantages, it also had obvious drawbacks: the historical and cultural value of this famous diamond would be significantly diminished.

(9) Recutting the Koh-i-Noor

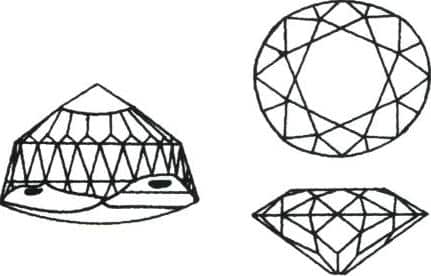

The diamond’s outward appearance also drew the displeasure of Prince Albert, and perhaps Queen Victoria as well. The diamond weighed 186.50 ct; in the circular multifaceted rose-cut portion, there was a triangular facet, beneath it a large cleavage face, with a small cleavage face on the side and several other types of blemishes. Although the diamond was very large, it lacked brilliance and the optical effects people expected; at that time, it was valued at £140,000.

After the exhibition at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, the British royal family decided to recut this historically significant famous diamond. To achieve better optical effects, they made fundamental changes to the shape and weight of what was then the most historically important diamond in existence. The decision may have been made after careful consideration. However, it is certain that the choice was driven solely by the diamond’s direct utility and completely disregarded its historical and cultural value. Although differing opinions were raised about recutting the Koh-i-Noor diamond, they were not accepted by the British royal family.

The recutting of the Koh-i-Noor diamond was commissioned to the then-famous Coster Diamonds of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, but the actual cutting work was carried out in Britain and completed by diamond cutter Voorsanger under the supervision of the Queen’s mineralogist James Tennant. The recutting began on July 16, 1853, took 38 days, cost £8,000, and reduced the weight to 108.90ct. After recutting the girdle diameter of the diamond increased; the original diamond’s facets were used as the new girdle, and the recut diamond was made oval.

The appearance of the Koh-i-Noor diamond was improved to some extent by the recutting, but its historical value was greatly affected. Before the recutting, the standard round brilliant cut had not yet been invented; that standard round brilliant faceting was devised in 1919 by Marcel Tolkowsky, who calculated the optimal angles and proportions for cutting a diamond to produce the best optical performance—results that diamond cutters had sought for a very long time.

The recut Koh-i-Noor diamond (Fig. 6-2) was set in a brooch, a bracelet, or a specially made circular ornament and worn by Queen Victoria; that circular ornament is now exhibited at the London Museum.

Figure 6-2 The Koh-i-Noor diamond after recutting

(Left image shows the shape before recutting; right image shows the shape after recutting)

(10) The Koh-i-Noor Diamond and the British Royal Family

Since Queen Victoria, the Koh-i-Noor diamond has been in the British royal family. After Queen Victoria died in 1901, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was set in the centre of the front cross of the crown of Queen Alexandra, wife of King Edward VII (Fig. 6-3). This crown featured several new elements: platinum replaced gold, and it had four arches (previously there had been only two). This British crown was also the first crown to be set with the Brightness of the Mountain diamond.

Figure 6-4 Queen Mary's crown set with the Koh-i-Noor diamond

The Koh-i-Noor diamond and replicas of the Cullinan III and Cullinan IV diamonds shown in the picture are all crystal-made copies.

In 1937, Queen Mary wore the crown to attend the coronation of her son, George VI.

The crown frame made of platinum by Queen Alexandra is now in the London Museum and is set with a replica of the Koh-i-Noor diamond made of special lead glass. Queen Mary’s crown frame, now displayed in the Jewel House at the Tower of London, is set with a Koh-i-Noor diamond replica made of crystal, as well as replicas of the Cullinan III and Cullinan IV diamonds. The shapes of these Koh-i-Noor replicas are all those of recut stones.

After George V, King George VI ascended the throne. In 1937, George VI’s wife, Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon, received this diamond and set the Koh-i-Noor into her own crown (Fig. 6-5).

The metal frame of this crown is made of platinum and is set with 2,800 diamonds, the cuts being mainly cushion with some rose and brilliant cuts. The Koh-i-Noor is mounted on the central cross at the front of the crown; the cross at its top is set with the Lahore Diamond, which the East India Company presented to Queen Victoria in 1851. Below the Bright Star of the Mountain, on the circlet, is set the Turkish Diamond, which Sultan Abdul Medjid of Turkey presented to Queen Victoria in 1856.

On April 9, 2002, at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother held at Westminster Abbey in London, the diamond was placed on the Queen Mother’s coffin, allowing the world to once again behold the dazzling brilliance of the “Koh-i-Noor” diamond.

The Koh-i-Noor has never been set in the crown of a British male monarch, which may be a coincidence. Legend has it that any man who owns and wears this diamond will encounter grave danger, a belief that has persisted for many years. But it has not held for women: Queen Victoria possessed and wore the diamond and reigned successfully for a long time.

Now the Koh-i-Noor diamond is set in the crown of Queen Elizabeth II. As a piece of British royal jewellery, it is kept in the Tower of London, displaying to the world the wealth and status of the British monarchy, while quietly telling the long history of this diamond invites speculation about its mysterious future.

Section II The Long and Storied Sancy Diamond

The Sancy Diamond was acquired by Nicolas Harley (Nicholas Harley, also known as the Marquis of Sancy) in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey). He was the envoy sent by France’s Henry III to the Ottoman Empire, and it is thought he purchased the diamond around 1570.

In 1604, the Marquis of Sancy sold the diamond to King James I of England through his brother, who was then the French ambassador to England, and agreed to pay the full amount in instalments over three years. Thus, the Sancy Diamond came to England. However, its time as part of the English Crown Jewels was not long. Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria removed many gems from the royal collection, including the Sancy Diamond and the Mirror of Portugal diamond, to sell or use as collateral in an attempt to save their faltering throne.

Unable to raise funds to redeem the jewels used as collateral, the Sancy and the Mirror of Portugal were later sold to the French cardinal Jules Mazarin, who paid a total of 360,000 livres for the two diamonds, making them the finest diamonds in Mazarin’s collection. He left eighteen fine diamonds to the French royal family, including the famous Sancy and the Mirror of Portugal; the diamonds from Mazarin’s collection are collectively known as the “Mazarin” Diamonds.

Before Louis XV became king, the Sancy and the Regent diamonds were already being worn. Marie Leczinska, wife of Louis XV, often used the Sancy as a pendant and the Regent as a hair ornament. When Leczinska’s son, the Dauphin of France, married María Teresa of Spain, the Sancy was mounted on his hat, and Marie Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI, often set the Sancy, the Regent and other Mazarin diamonds into jewellery as drops on feathers and flowers.

During the French Revolution, the Sancy diamond and other treasures were stolen from the French royal treasure house, and the Sancy diamond was not recovered in time. After a period of obscure history, the diamond returned to the French treasury. An adjutant in Napoleon’s army, to raise one million francs for military funds, once pawned many diamonds in Madrid, including the Sancy. In 1828, a French merchant sold it for $100,000 to the Russian Demidoff family.

In 1865, Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy of Bombay, India, purchased the Sancy Diamond, but soon sold it on to a French jeweller. In 1867, the diamond was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where it was offered for one million francs.

After that, the Sancy Diamond disappeared from public view for nearly 30 years. In 1906, William Waldorf Astor purchased the diamond for $500,000. The diamond was displayed at the Louvre’s centennial jewellery exhibition in France in 1962. In 1978, after protracted negotiations with the heirs of the Astor family, several French museums paid $1,000,000 to buy the Sancy Diamond from the fourth Viscount Astor. The diamond is now exhibited in the Apollo Gallery of the Louvre in Paris for public viewing.

Section III The Age-Old Orloff Diamond

The Orloff Diamond was the inspiration for Wilkie Collins’s famous novel The Moonstone. Legend has it that the Orloff Diamond was one of the eyes of a statue of the goddess Vishnu (in Brahminism). In the mid-17th century, a French army occupied the southern Indian city of Trichinopoli. A French soldier stationed there flatteringly ingratiated himself with the temple’s priest and was appointed a temple guard. One day, this scheming French soldier pried out the god’s eye, stole the diamond, and fled to Madras.

There, the diamond was sold for £2,000 to the captain of a British ship anchored in the harbour. After returning to London, the captain sold the diamond to a jeweller for £12,000. The diamond was certainly sold in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, to Count Gregori Gregorievich Orloff; at that point, the diamond was named after its owner as the Orloff Diamond. It is said Orloff paid 400,000 rubles for it, the transaction taking place around 1775.

Before Catherine the Great became Empress of Russia, Orloff had been her lover. Orloff bought the diamond at such an exorbitant price and presented it to Catherine the Great to win her favour and propose marriage to her. Catherine accepted the diamond, giving in return only a marble palace in Saint Petersburg; nothing else was received. In 1783, Orloff died in an asylum, having become mentally unwell.

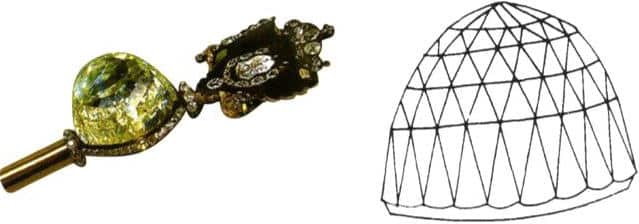

Catherine the Great had the Orloff Diamond mounted on the imperial sceptre designed by C. N. Troitinski; it resembles a brilliant rocket, set with eight rows of round diamonds in three directions, some diamonds weighing up to 30 ct, with the Orloff Diamond mounted at the top of the sceptre. Above it is a double-headed eagle bearing the emblem of Russia on its breast (Fig. 6–8). In 1981, an illustrated volume recorded the Orloff Diamond’s weight as 189.62 ct.

Section IV The Shah Diamond with Carved Inscriptions

On the top of this diamond, there is an exquisitely carved inscription in Persian, the contents of which are as follows:

Burhan Nizam Shah: 1000 (i.e., 1591 CE)

Son of King Jahangir — King Jahangir 1051 (i.e., 1641 CE)

Fath Ali Shah (Fathʿh Ali Shah) (i.e., 1842 CE)

The first line of the inscription names the ruler of Achmednager province in India. The last line bears the name of the Persian king, which makes it certain that this diamond was taken from the treasury of the Mughal dynasty. At the top of the diamond, there is a small circular groove; it is clear that this was made to support a ringed cord so it could be hung on the Peacock Throne.

The Shah diamond has played a significant role in history, successfully preventing a war between Russia and Persia. Under the 1829 Treaty of Turkmenchay, Persia ceded some wealthy northern territories to Russia. Outraged, a group attacked the Russian embassy in Tehran and killed the ambassador, Aleksander Griboyedov. The Russian tsar threatened military retaliation. To appease the situation, the Persian government presented the Shah diamond as a gift to Tsar Nicholas I, who accepted the diamond and added it to the Russian imperial jewels.

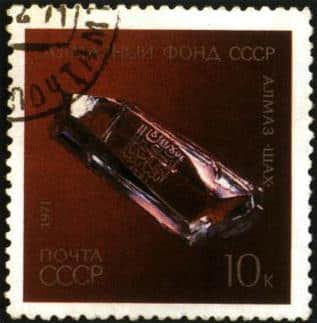

In August 1914, for security reasons, the Shah diamond was moved from St. Petersburg to the Kremlin in Moscow, where it was kept thereafter. In 1971, the Soviet Union issued a commemorative stamp featuring the Shah diamond (Fig. 6–10).

Section V The Extraordinary Hope Diamond

(1) The Past and Present of the Hope Diamond

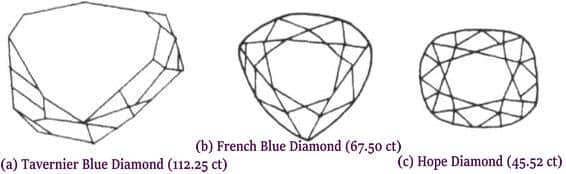

The Hope Diamond originates from the Tavernier Blue Diamond, a rough stone weighing 112.25 ct, mined in the Kollur mine area of Golconda, India, and blue in colour. The diamond was brought from India to France by the famous French jeweller Tavernier.

After completing his sixth trip to India and returning to France, Tavernier was summoned by King Louis XIV, who had a passion for jewels, and was ordered to bring the gems he had acquired in India. The king purchased 54 large diamonds from Tavernier (including the Tavernier Blue) and 1,122 smaller diamonds. Tavernier used the proceeds from selling the diamonds to buy the baronial title of Aubonne in Switzerland.

Louis XIV was very dissatisfied with the original Indian cut of the Tavernier Blue; the faceting of the Indian cut was mainly used to remove flaws from the diamond, usually leaving an irregularly shaped cut with poor optical performance, weak fire, and rough workmanship. In 1673, he ordered the royal jeweller Sieur Pitau to recut the diamond. After recutting the stone took on a triangular, almond-like shape, its weight reduced to 67.50 ct, and it was named the French Blue Diamond or Blue Diamond of the Crown. Louis XIV liked this blue diamond very much and often wore it around his neck.

In 1749, King Louis XV of France ordered that the blue diamond be set into the Order of the Golden Fleece, which represented the power of the French chivalric order. In 1774, the king’s grandson succeeded to the throne as King Louis XVI of France. His misrule increased public resentment, and finally, on July 14, 1789, a popular uprising broke out. The king fled hastily with the Queen and some royal jewels, but was captured at Vincennes, and the seized jewels were returned to the Garde Meuble, the French royal treasury.

The French royal treasury had long been a prime target for thieves; at that time, aside from guards on duty, the treasury had no other security measures. As a result, one of the most sensational jewel thefts in the history of jewellery occurred. Some of France’s most historically significant and legendary gems disappeared, including the French Blue, the Regent Diamond, the Sancy Diamond, and the Mirror of Portugal.

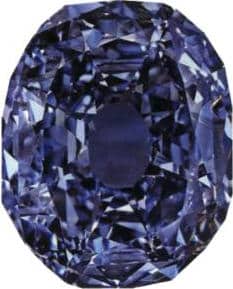

Later, the Regent Diamond and the Sancy Diamond were subsequently recovered. But the Portuguese Diamond of the Mirror disappeared completely after that. The French Blue also went missing for nearly 40 years, until 1830, when banker and gem collector Henry Philip Hope purchased a deep-blue diamond similar to the French Blue on the London market for £18,000; it was very likely part of the French Blue and weighed only 45.52 ct. After Hope acquired this diamond, it was named the Hope Diamond.

After the theft of the French Blue, to cover up the theft, there was an intentional recutting of the French Blue—this possibility exists. Following a period of obscure history, the French Blue was split into three pieces; the largest of these, after cutting, weighed 45.52 ct, and this diamond is the present Hope Diamond. Thus, the mysterious Tavernier Blue Diamond, after being cut twice, saw its weight reduced to 45.52ct. The cut styles of the Hope Diamond in different historical periods are shown in Figures 6–11 and 6–12.

(2) The Henry Philip Hope Family and the Hope Diamond

Henry Philip Hope was Dutch and especially fond of collecting colored diamonds. In 1839 he published an illustrated catalog of his collection, in which the Hope Diamond was described as: this is a unique diamond, with a sapphire-like beautiful color and the dazzling brilliance characteristic of diamonds; because of its special color and relatively large size along with other excellent qualities, it can be called unparalleled in the world — even among royal jewels worldwide there is no such specimen. This diamond was set in an exquisitely crafted round mount with small rose-cut diamond accents; these rose-cut diamonds were uniform in size, shape, cut, and clarity, each weighing about one ct.

Henry Philip Hope was a bachelor; upon his death, his estate passed to his three nephews. The eldest nephew, Henry Thomas Hope, inherited the Hope Diamond. In 1851, he lent the Hope Diamond for exhibition at the Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in London. In 1855, he again lent it for display at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. At other times, the Hope Diamond was kept in a bank vault.

In 1861, Henry Thomas Hope’s only daughter, Henrietta Hope, married Henry Pelham-Clinton. After Henry Thomas Hope died, his diamond and other property passed to his widow, Anne Adele. Before Adele died in 1884, she entrusted all of the Hope estate (including the Hope Diamond) to her grandson Henry Francis, stipulating that he would inherit her estate upon reaching the age of legal majority and changing his surname. In 1887, Francis Hope obtained his grandmother’s inheritance. However, he only acquired equitable title to the estate and, without the court’s permission, could not sell any of the assets he had received.

Afterwards, Francis Hope fell in love with the American singer Mary Augusta Yohe and married her in Hempstead in 1894. The following year, Hope went bankrupt. Although he could obtain necessary living expenses by selling the inherited collection of paintings, his expenditures exceeded the income from those sales, so he petitioned the court to allow the sale of the Hope Diamond. The diamond had been kept at Parr’s Bank; it brought neither joy nor utility, and even his wife Mary had worn it only twice.

Meanwhile, after prolonged legal proceedings, in 1901, the court permitted Francis Hope to sell the Hope Diamond. He sold it to Adolph Weil for £29,000. After that, the Hope Diamond was purchased in London by Simon Frankel and was carried to New York, USA, on the steamship Kronprinz Wilhelm in November 1901. In 1908, Frankel sold the diamond to Turkish diamond collector Selim Habib. In 1909, Habib sold the diamond in Paris to jeweller Simon Roesnan. In 1910, Roesnan sold the diamond to the Cartier firm. Cartier then sold the diamond to Mrs Evalyn McLean.

Kopírování @ Sobling.Jewelry - Výrobce šperků na zakázku, továrna na šperky OEM a ODM

(3) The Origin of the “Cursed Diamond”

Most of the catastrophic legends about the Hope Diamond are connected with American heiress Mrs Evalyn McLean and her family. Because members of her family suffered successive misfortunes after wearing the diamond, the Hope Diamond became known as the “cursed diamond.” This readily leads people to think of the diamond’s past owners and the various misfortunes they once encountered. For example, Tavernier suddenly lost the wealth he had when he was 80. People believed this blue diamond was an incarnation of a deity that had brought disaster upon Tavernier and the subsequent owners of the stone.

Evalyn’s father was a gold mine owner in Colorado, USA, and the mine brought them enormous wealth. Evalyn and her brother lived the extravagant life of wealthy youngsters. At 22, she married Edward McLean, the son of the owner of the Washington Post. Before the wedding, they went together to the Cartier jewellery company to select a wedding present paid for by Evalyn’s father. Cartier offered the big buyers a platinum diamond necklace and three gemstone pendant necklaces, namely a large pearl weighing 32.25 lyi (1 lyi = 64.8 mg), a 34.50 ct emerald and a huge pear-shaped diamond of 94.80 ct called the Star of the East; they purchased this large diamond. Then, in less than four months, they spent a total of $200,000 in Europe on extensive purchases.

In 1910, the McLeans returned to Paris, and Pierre Cartier brought the Hope Diamond to the hotel where they were staying to show them the stone and tell them its history. But Mrs McLean refused to buy the Hope Diamond because she did not like the setting of the diamond. A few months later, Pierre Cartier brought the reset Hope Diamond to New York. This time, Mrs McLean bought the diamond for $180,000 and paid for it in instalments (Fig. 6–13).

The “misfortunes” that the Hope Diamond seemed to bring to the McLean family followed in quick succession: first, her nine-year-old son died in an automobile accident; her daughter died at 25 from an overdose of sleeping pills; her husband’s health deteriorated; and Mrs McLean herself died from sleeping pills. However, none of this was the “fault” of the Hope Diamond, and the “curse” did not afflict everyone who ever touched the stone.

After Evalyn’s death, the famous American jeweller Harry Winston bought the diamond and donated it to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington. On November 10, 1958, Winston mailed the Hope Diamond to Washington in an ordinary registered letter, paying postage of $145.29 and accompanying it with an insurance policy for $1,000,000.

Since then, the historically significant Hope Diamond has been displayed to the public under a thick glass dome and monitored by an extremely sophisticated and complex electronic system for viewers to admire.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Hope Diamond’s entry into the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in 2009, the museum officially announced that the Hope Diamond would be remounted in a brand-new setting for public exhibition. The Hope Diamond was removed from its original jewellery piece and cleaned, and the cleaned, loose Hope Diamond was also put on public display. This method of exhibition was the first of its kind for the Hope Diamond since its arrival at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

On November 18, 2010, the Hope Diamond was officially exhibited to the public in a brand-new setting called the “Embrace the Hope Diamond” (Fig. 6–15); Harry Winston, Inc. created the new design. This mounting was chosen from three alternative proposals. On January 13, 2012, the diamond was restored to its original, historically significant setting.

(4) Gemological Characteristics of the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond not only has a long history but also possesses very distinctive scientific properties. Natural diamonds can be divided into two main types, called Type I and Type II diamonds. Type I diamonds are 1,000 times more common than Type II diamonds and range in colour from white to pale yellow. Each type can be further subdivided into two subtypes, labelled a and b; among these, Type IIa diamonds are about 1,000 times more common than Type IIb diamonds. In other words, Type IIb diamonds are extremely rare.

All Type IIb diamonds appear blue or grey-blue in colour, most of which come from the Premier diamond mine in South Africa. The properties of Type IIb diamonds are very unusual—not because they are blue, but because they are electrical semiconductors. Moreover, they have very special scientific applications.

Since the 1950s, people have mastered methods of using electron radiation to optimize and alter the colour of diamonds. In other words, Type I diamonds can be changed into blue diamonds. However, diamonds artificially turned blue still belong to Type I diamonds and are good electrical insulators, whereas natural Type IIb blue diamonds can conduct electricity.

The famous British gemologist Robert Webster experimentally confirmed this scientific fact. He placed two blue diamonds on an insulated metal plate, then used an insulated probe connected to a power source to test them separately. One diamond showed no reaction, indicating it was an electrical insulator and therefore confirmed to be an artificially colour-treated blue diamond. The other diamond, after a few seconds of electrification, began to glow and heat up—this was a natural blue diamond; if electrified for too long, the diamond would transform into diamond’s allotrope—graphite—and ignite.

Since the Hope Diamond entered the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, it has left only four times. In 1962, it was exhibited at the French Jewellery Centenary Exhibition held at the Louvre in Paris; in 1965, it was displayed at the Rand Easter Show in South Africa; and in 1984 and 1996, it was briefly returned to the company exhibition established by the donor Harry Winston in New York.

In 1988, experts from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) conducted a comprehensive scientific examination of the Hope Diamond; its dimensions are 25.60mm×21.78mm×12.00mm, and its weight is 45.52 ct. In 1996, GIA experts graded the Hope Diamond’s colour as Fancy Deep Greyish Blue. After exposure to ultraviolet Light (wavelengths under 350 nm) and then turning off the UV lamp, on a dark background, the Hope Diamond exhibits phosphorescence, and the phosphorescent colour is deep red (Fig. 6-16), a phenomenon that greatly surprised researchers and is difficult to explain.

Section VI The Timeless Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond

(1) The Legendary History of the Wittelsbach Diamond

The Wittelsbach Diamond is a single diamond with a legendary history. In 1667, the diamond appeared in Spain as part of the dowry when Margaret Theresa, daughter of King Philip IV of Spain, married Leopold I of Austria.

In 1722, the diamond passed to Leopold I’s granddaughter, Maria Amalia, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I, as her dowry when she married Charles Albert of Bavaria (later Charles VII), Elector of the Wittelsbach family. The diamond thus moved from Spain’s Habsburgs into the hands of the Wittelsbachs in Munich.

In 1745, the Wittelsbach Diamond was set for the first time into the Bavarian Elector’s Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1761, when the Wittelsbach Diamond was transferred from the Elector’s private treasury to the state treasury, it was described as: “of excellent clarity, beautiful color, incomparable by any other diamond, valued at 300,000 florins, weighing 36ct.”

In 1806, when Maximilian IV became King of Bavaria, the Wittelsbach Diamond was the principal ornament on his crown (Fig. 6–18). The diamond was set on the the Bavarian crown for more than 100 years. In 1918, after World War I, all the Bavarian royal property was converted into a special fund. In 1921, the diamond made its last public “appearance,” at the funeral of Ludwig III of Bavaria. This blue diamond belonged to the Bavarian Wittelsbach family continuously from 1722 until 1951.

(2) The Sale and Auction History of the Wittelsbach Diamond

During the Great Depression in 1931, the Wittelsbach family attempted to sell the diamond, but under the economic conditions at the time, they could not find a buyer. The diamond was not sold until 1951. In 1958, the Wittelsbach Diamond was exhibited at the World’s Fair in Brussels, Belgium.

In 1961, the Wittelsbach Diamond appeared in Antwerp, where a diamond dealer consulted diamond expert Joseph Conkmer about an old mine-cut diamond. The dealer planned to recut the stone; when Conkmer saw it, he was very surprised. Based on his knowledge and experience, he judged it to be a historically significant blue diamond. He held the diamond up for careful inspection and then muttered to himself that recutting it would be a “crime” that would destroy its historical value. Conkmer refused the request to recut the diamond and contacted some jewellers to jointly purchase the historically significant stone.

In 1964, the Wittelsbach Diamond became part of a private collection. Later, Germany’s famous department store magnate Helmut Horten bought the diamond and presented it to his wife Heidi at their wedding in 1966.

It was reported that on December 11, 2008, at Christie’s in London, the Wittelsbach Diamond sold for $24.3 million. Even against the backdrop of a global economic downturn, the diamond fetched such a high “astronomical” price—the pre-sale estimate was £9 million—yet the hammer price set a new auction record. The head of international jewellery at Christie’s in London for that sale said, “It is my greatest honour and lifelong dream to encounter a museum-quality diamond like the Wittelsbach.” The buyer was the renowned British diamond dealer Laurence Graff.

Shortly after acquiring the diamond, Graff announced his plan to recut the Wittelsbach to remove flaws at the girdle, enhance its colour, and improve its clarity. On January 7, 2010, reports stated that the recutting had been completed. The diamond’s colour and clarity were improved to a certain extent; in the recutting process, a total weight was lost. The recut stone was named the Wittelsbach-Graff Diamond (Fig. 6-19).

Section VII The Resplendent Tiffany Diamond

Figure 6-21 Tiffany Diamond ribbon necklace

Figure 6-22 Hollywood actress Audrey Hepburn wearing a Tiffany diamond ribbon necklace

Figure 6-23 "Bird on a Rock" brooch

Figure 6-24 Tiffany diamond necklace

Section VIII The Aesthetically Brilliant Oppenheimer Diamond

Section IX The Magnificent Williamson Diamond

The Williamson Diamond is a famous pink diamond. Dr John Thoburn Williamson discovered it at the Mwadui mine in Tanzania, which is currently the largest kimberlite-hosted diamond mine in the world by area. This diamond-bearing kimberlite pipe was discovered in March 1940 by a research team led by the renowned Canadian geologist Dr John Williamson, after five years of arduous effort and hard work.

The rough diamond was weighed 54.5ct and named after Dr John Williamson. In November 1947, when Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom married Prince Philip, Williamson presented the rough diamond to Princess Elizabeth, who is now the Queen Elizabeth II. The diamond was cut in London by diamond cutters Briefel and Lemer, and the polished diamond weighed 23.60 ct. Because of its unique colour and excellent quality, it was once considered one of the finest diamonds in the world. In 1952, Cartier was commissioned to set the diamond at the centre of a floral brooch, and the petal diamonds were also cut from stones from the Mwadui diamond mine (Fig. 6–26). This diamond now belongs to the British Crown Jewels.

Section X The Unique Dresden Green Diamond

(1) The History of the Dresden Green Diamond

During the reign of the Elector of Saxony in Dresden, Germany — the Strong King Frederic Augustus I — the city was one of Europe’s cultural and artistic centres and constructed many baroque-style buildings and a large collection of sculptures, paintings, and other works of art. In addition, King Augustus had eight galleries built on either side of Dresden Castle specifically for jewels and other high-value artworks; the interiors were decorated in the French style and called the Green Vault, with the eighth gallery used exclusively to display the royal jewels.

The succeeding Elector — the son of Frederic Augustus I, Frederic Augustus II — bought a fine green diamond in Leipzig in 1742. It was pear-shaped, with 58 facets, and weighed 40.70 ct. Augustus II kept this diamond in the Green Vault, and except for the occasional wearing, the stone quietly remained on display there for more than two centuries.

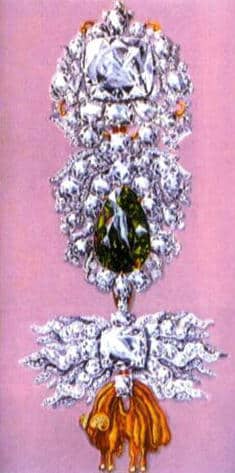

Initially, by Augustus II’s directive, the Dresden Green Diamond was mounted on a Golden Fleece medal. In 1746, the king ordered the medal to be remade, combining the Dresden Green Diamond with the Dresden White Diamond (Fig. 6–28).

Among them, the Dresden White Diamond is a white, square-cut diamond weighing 49.71 ct, purchased by the robust King Augustus; the Dresden Green Diamond had once been set in a hat, while the Dresden White Diamond, removed from the Order of the Golden Fleece, was set in an epaulette. In addition, there is a Dresden Yellow Diamond, a round-cut stone weighing 38 ct.

Regarding the origin of the Dresden Green Diamond, people generally believe it came from India, but this belief lacks definite evidence. Therefore, the Dresden Green Diamond may have come from Brazil; after the 1820s, Brazil gradually replaced India as the world’s main diamond-producing country. Augustus II bought this diamond from a Dutch merchant. Amsterdam was the world’s diamond-cutting centre in the 17th century, and the discovery of Brazilian diamonds sparked a revival of Amsterdam’s diamond-cutting industry, with rough stones from Brazil continuously sent to Amsterdam. This inference might serve as a basis for judging the origin of the Dresden Green Diamond. However, one thing is certain: because of its distinctive colour and size, anyone who has seen the Dresden Green Diamond would be deeply impressed; it is estimated that the rough stone weighed about 100 ct.

During World War II, the jewels stored in the Dresden Green Vault were moved to Königstein, the Saxon fortress by the Elbe River. Thus, these treasures escaped the Allied heavy bombing of Dresden, in which most of Dresden’s buildings were destroyed.

After the war, these treasures were taken to Moscow, including the three Dresden diamonds (the Dresden Green, the Dresden White, and the Dresden Yellow). In 1958, these treasures were returned to their original owners, and now these three diamonds are again displayed in the Green Vault for visitors.

(2) Gemological Characteristics of the Dresden Green Diamond

So what are the gemological characteristics of the Dresden Green Diamond? In 1988, two senior gemologists from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) conducted the first detailed gemological examination of this gem in Dresden. The results showed that the Dresden Green Diamond not only possesses exceptional quality but is also a rare Type IIa diamond, containing no nitrogen or other impurities. Its clarity grade is VS1, meaning this green diamond has relatively high clarity. The size of this diamond is 29.75mm×19.88mm×10.29mm. Even more surprisingly, its symmetry was graded “Good” and its polish was graded “Very Good.” For a diamond cut in 1741, such cutting standards are quite astonishing and indirectly attest to the cutting craftsmanship of the period. Additionally, the Dresden Green Diamond has a natural green body colour, ranging between the vivid green of an emerald and the grey-green of chrysoprase, and its colour is beautiful from every viewing angle.

At the time, accurately determining the weight of this diamond was quite troublesome because the diamond was extremely precious and difficult to remove from its metal mounting; forcibly removing it could have damaged the metal setting. In the end, the gemologists racked their brains and finally obtained the weight data: 40.70 ct.