Enfes Takı Yapımı için Emaye ve Düz Tabakalı Emayede Ustalaşabilir misiniz?

Cloisonné & Flat Enamel Jewelry Making Guide: Techniques, Firing, Polishing

Giriş:

This comprehensive guide delves deep into the intricate art of enamel jewelry creation, focusing on two foundational techniques: Flat-Laid Enamel and Cloisonné. The first part, dedicated to Flat-Laid Enamel, explores metal substrate preparation, including doming and cleaning, followed by the detailed processes of applying back glaze, base glaze, and crafting the final surface pattern.

The subsequent section shifts focus to the more complex Cloisonné technique. It covers the meticulous preparation of metal materials—cleaning, doming, and crafting the essential metal wires—before guiding you through the core steps: wire-twisting, filling with enamel, firing, and achieving stunning gradient effects with transparent glazes. The content culminates with the crucial polishing process to achieve a flawless, glass-like finish.

Structured as a practical, step-by-step manual, this resource is an invaluable guide for jewelry designers, studios, and brands. It empowers creators to master the skills needed to produce vibrant, durable, and professionally finished enamel pieces, from elegant brooches to custom pendants.

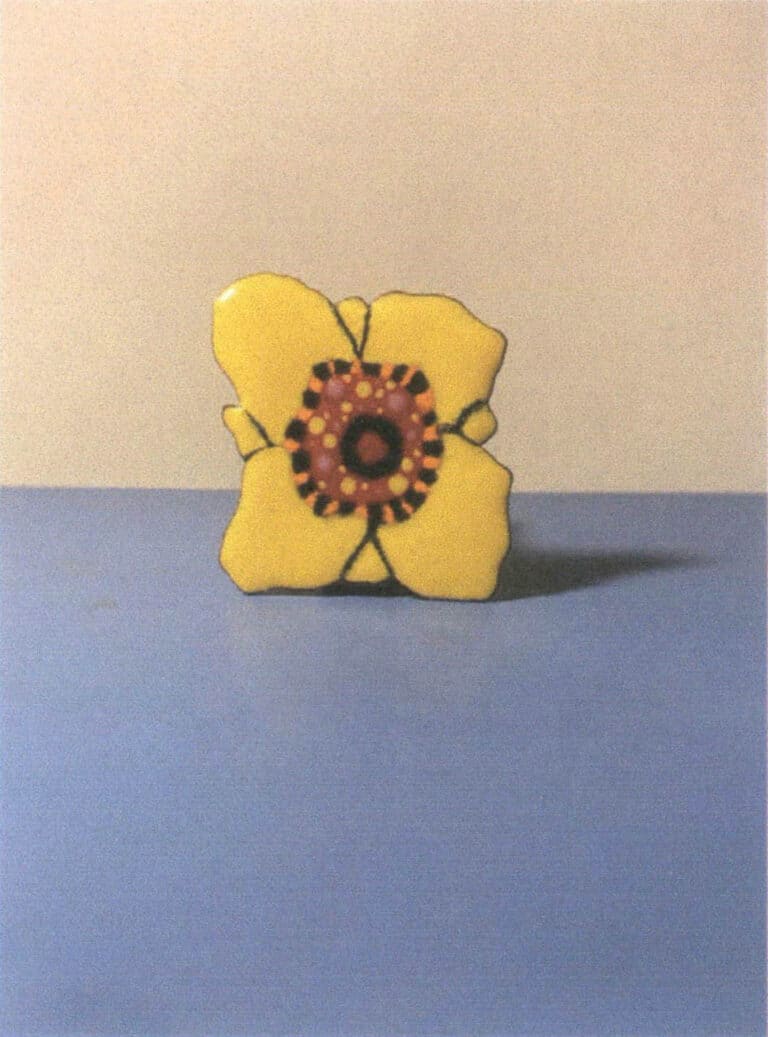

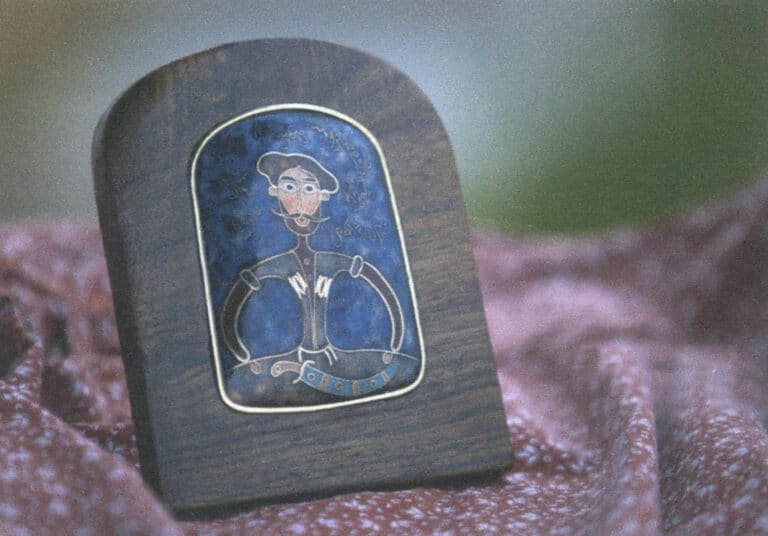

Work produced using the flat-laid enamel technique

İçindekiler

Section I Production of Flat-Laid Enamel

1. Pretreatment of Metal Bases

1.1 Planishing Treatment of Metal Bases

There are several methods to address the problem of metal plate deformation.

(1) Increase the thickness of the metal base plate. For example, a piece with an area of about 16 square centimeters (a square of 4 cm × 4 cm or a circle with a diameter of 4.5 cm) made of red copper, pure gold, or pure silver needs to be at least 1.5 millimeters thick to have any chance of not deforming after firing.

(2) Reduce the thickness of the enamel layer. For example, on a metal base plate 1 millimeter thick and with an area under 16 square centimeters, fire only a single layer of enamel glaze.

(3) Perform the metal base plate into a slightly convex shape, which can greatly reduce the risk of deformation.

Of these three methods, methods (1) and (2) each have their own problems.

The problem with Method (1) is that it often requires significantly increasing the thickness of the metal base to eliminate deformation. In jewelry design and production, whether to save costs or to consider wearing comfort, it is usually necessary to keep the weight of a piece as light as possible. If method (1) is used to prevent deformation, the increase in substrate thickness not only raises material costs but also increases the weight of the metal base; combined with the weight of the enamel glaze, the overall weight of the piece can more than double, which not only increases material costs but also greatly affects comfort when worn.

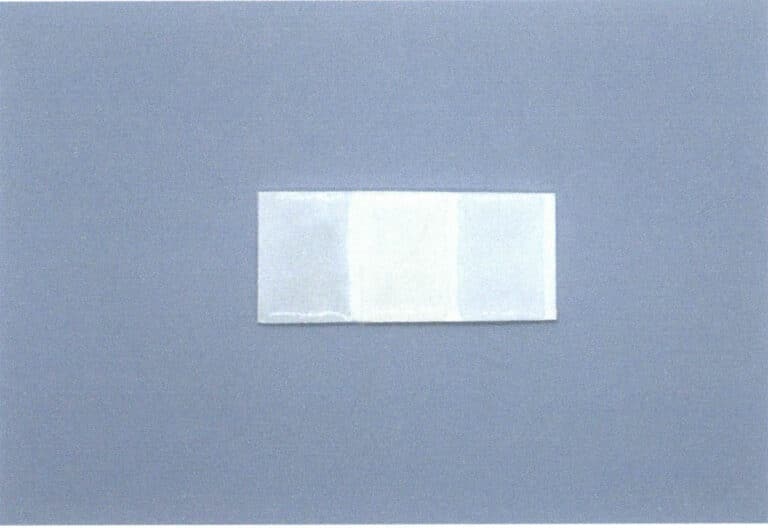

The problem with method (2) is that most types of enameling cannot achieve the best results if only a single layer of glaze is fired during the process. If an opaque glaze is used, a single layer often provides poor coverage, inadequate color saturation, and may even reveal the base; if a transparent glaze is used, a single layer typically yields colors that are too pale and cannot achieve rich and delicate color effects. Effects such as shading and gradients generally require three or more layers of glaze. Figure 4-3 shows the effect of firing only one layer of enamel on a metal base: on the left is French F300 opaque pink glaze fired on a copper backing, and on the right is French No. 616 transparent purple glaze fired on a silver backing. As can be seen, with only one layer of glaze, the opaque glaze cannot uniformly cover the color of the copper backing, and the transparent glaze, being very light in color, also cannot uniformly cover the silver backing.

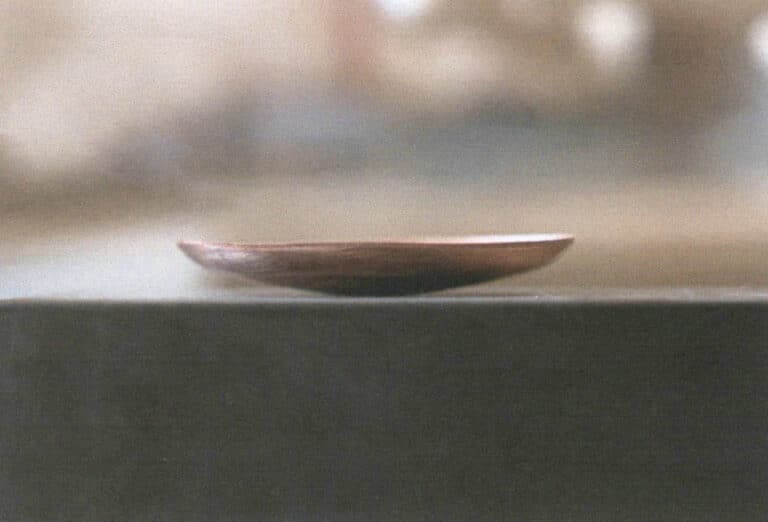

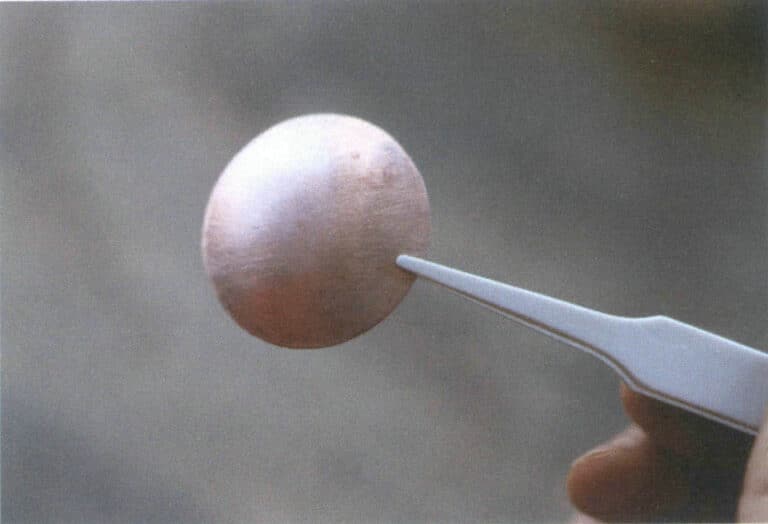

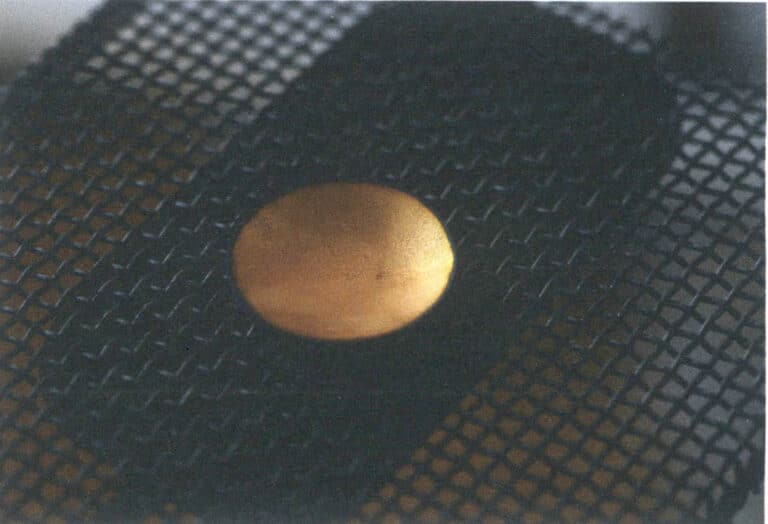

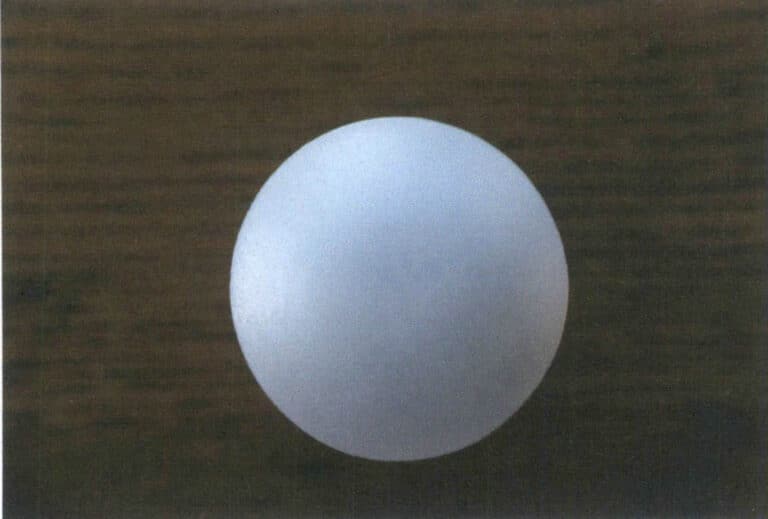

Therefore, a better solution to prevent deformation is method (3), which is to perform the metal base into a slightly convex shape. With this treatment, the strength of the metal base is increased without increasing its thickness, thereby reducing the occurrence of deformation. Figure 4-4 shows a 1 mm thick, slightly domed red copper plate; when the metal base is raised to this extent, it can basically prevent deformation. Metal bases treated in this way have greatly increased strength. For a pure copper or pure silver plate of about 16 square centimeters in area, for example, if subjected to convex preforming, the thickness of the metal base can be reduced to 0.8 mm.

Figure 4-3 Effect when only one layer of glaze is fired

Figure 4-4 Red copper plate formed into a slight dome

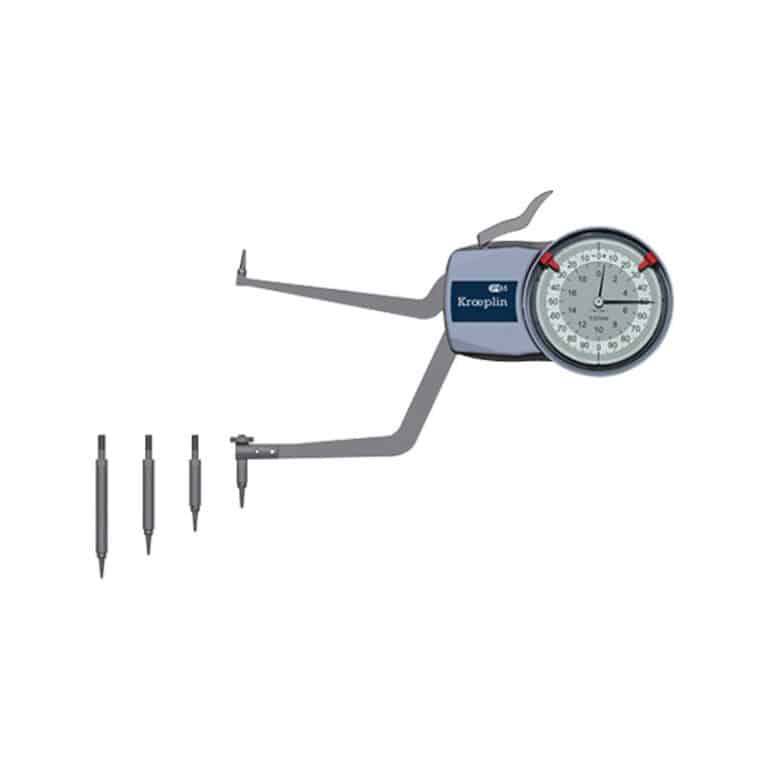

Figure 4-5 Steel dapping blocks

Figure 4-6 Ordinary soup spoon

The specific steps for doming the metal base plate are as follows (taking a circular pure copper plate with a thickness of 1 mm and a diameter of 4 cm as an example).

ADIM 01

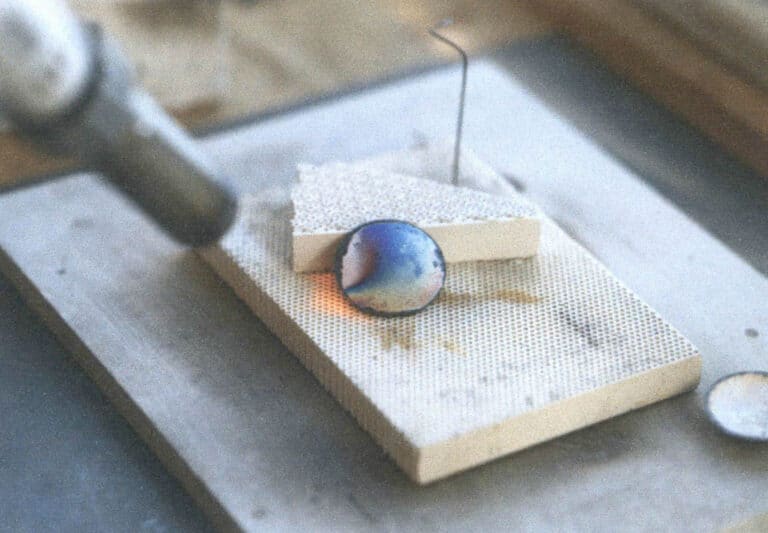

Anneal the metal base plate that has already been sawn and had its edges filed smooth; you can use either a torch or an enamel kiln. An enamel kiln is suitable for annealing multiple metal pieces at once; a torch does not require preheating like a kiln and is relatively more convenient, suitable for single items or small works. It is important that the annealing be thorough, meaning the entire metal base plate should become fully red after sufficient heating. If the annealing is insufficient, the metal base plate will not be soft enough, making it difficult to dome in the next step or causing visible tooling marks after doming. When using an enamel kiln to anneal the metal base plate, the temperature can be set to 850 °C, and the plate left in the furnace until it is uniformly red, then removed. If using a torch to anneal the copper plate, first use the outer flame to circle the edge of the copper plate and slowly rotate, gradually reducing the circle radius, and finally concentrate the flame on the central part of the plate until the entire plate becomes red. Figure 4–7 shows the situation of annealing the metal base plate with an enamel kiln, and Figure 4–8 shows the situation of annealing the metal base plate with a torch.

Figure 4–7 Annealing the metal base plate with an enamel kiln

Figure 4–8 Annealing the metal base plate with a welding torch

ADIM 02

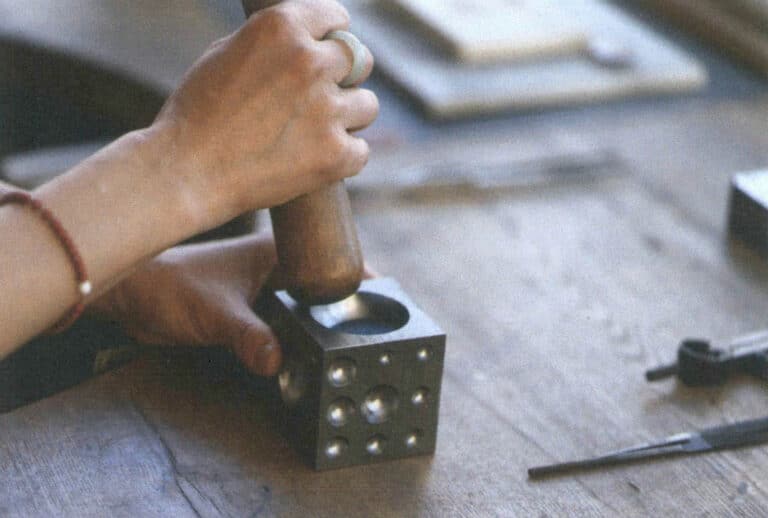

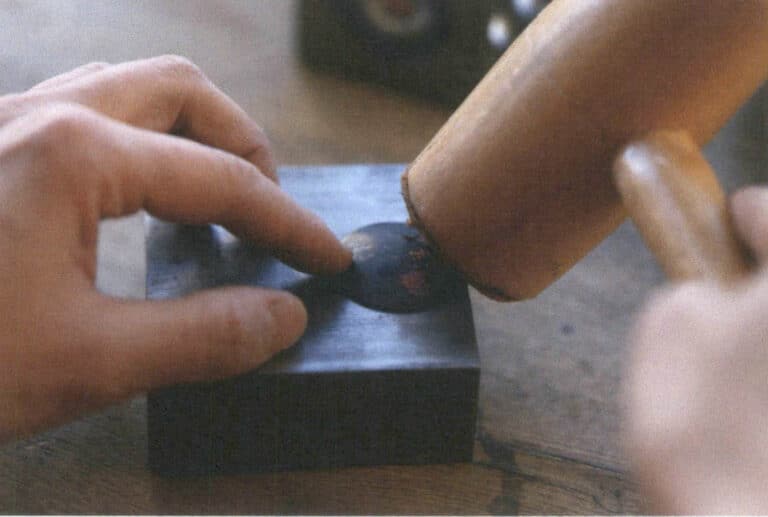

After the red-hot metal base plate has cooled, place it into a mold and use a wooden, rounded pestle-like tool to firmly roll downward. Note: roll, do not strike — that is how the metal base plate is formed into an even recessed shape and retains a smooth curve. The pestle-like tool can be wood or rubber; its end should be rounded, sufficiently hard but not abrasive to the metal surface. A wooden mortar pestle or tea-pounding stick can be used as a substitute. The most important point is that the tip must be polished into a smooth hemispherical shape so the metal base plate can be worked into a smoothly curved convex surface. Figure 4–9 shows a wooden pestle tool for forming a convex shape in the metal base plate, and Figure 4–10 shows the process of forming the convex shape. Once the metal base plate has become arched, flip it over and place it on a steel platform, then gently hammer the surrounding edges flat with a wooden or rubber mallet, as shown in Figure 4–11 — this yields a metal base plate that is slightly raised in the center, as shown in Figure 4–12. Note that the metals used for enameling, such as pure gold, pure silver, and pure copper, are not very hard, and even small amounts of pressure can deform them, so when rolling downward with the wooden pestle, apply the force evenly; this ensures the convexed metal base plate presents a smooth plane. If the force is uneven, discontinuous bumps easily form on the metal surface. Even slight unevenness in the metal base plate can greatly affect subsequent enameling firing steps and the final appearance of the piece.

Figure 4-9 Wooden tool for forming a convex shape in the metal base plate

Figure 4-10 Convex treatment of the metal base plate

Figure 4-11 Flattening the edge

Figure 4-12 Convex treatment completed

1.2 Cleaning of Metal Bases

In the enameling process, the metal base requires that it be quite clean. If the metal base used is not sufficiently clean, oils, dust, or other impurities adhered to it will affect the bonding between the enamel glaze and the metal, causing bubbles, cracks, black spots, or affecting the color appearance of the glaze; they may also affect the strength and durability of the glaze’s adhesion to the metal.

Therefore, before firing the enamel, the metal base must be thoroughly cleaned.

Pickling is generally used to clean the metal base, which means immersing the unfired metal base in an acid solution for a period of time and using the corrosive action of the acid to remove surface oils or oxides. The type of acid solution used for pickling should be chosen according to the metal in use; for example, in this case, the copper or silver items used in the example can be pickled with a dilute sulfuric acid solution or a dilute nitric acid solution; in all operational examples in this book, a dilute sulfuric acid solution is used. Figure 4-13 shows the acid box used for soaking copper and the acid box used for soaking silver. The acid in the box that soaked the copper turns blue because sulfuric acid reacts with copper to form copper sulfate. Acid pickling of different metals must be carried out in separate containers; otherwise, the purity of the metals will be affected.

To clean the metal used for firing enamel, prepare a dilute sulfuric acid solution with a concentration of at least 30%, immerse the metal base plate with the formed raised shape in the acid for 15~20 minutes, and observe until there are no traces of black oxides on the metal surface and the base plate appears smooth and shiny. The lower the acid concentration, the longer the soaking time. The reaction can be accelerated by warming the acid, but heating sulfuric acid generates toxic gases that are extremely harmful to humans; therefore, it is strictly forbidden to perform this operation in a nonprofessional studio without a good ventilation system.

If there are contaminants or stains on the metal base plate that are difficult to remove by pickling, you can first sand them with sandpaper and then perform pickling.

The specific pickling steps are as follows.

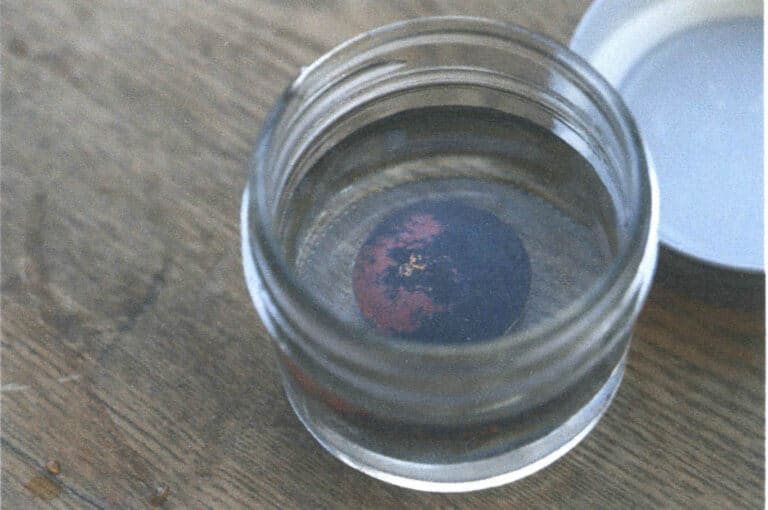

ADIM 01

Completely immerse the metal base, which has been processed into a slightly convex shape, in a dilute sulfuric acid solution with a concentration of about 30% for 15~20 minute; the exact time depends on the concentration of the prepared acid solution. In this step, you can observe fine bubbles forming on the metal base while it is soaked in the acid. These bubbles are gases produced by the reaction, indicating that the dilute sulfuric acid is cleaning the metal surface. More and denser bubbles indicate a more vigorous reaction; this can be used to judge whether the prepared acid concentration is appropriate. Figure 4–14 shows the situation of a copper substrate being soaked in the acid. Note that the container should be covered during the pickling process: although sulfuric acid is not volatile, the reaction with the metal produces irritating sulfur dioxide gas, which should be avoided as much as possible.

ADIM 02

After soaking for a sufficient time, remove the metal base plate and inspect it. If there are still dark red or black oxides that haven’t been removed, gently scrub them off with a copper brush or a relatively stiff scouring pad until the surface is completely clean and bright. Figure 4–15 shows the process of removing residual oxides with a scouring pad.

Figure 4-14 Acid pickling of the copper base plate

Figure 4-15 Removing residual oxides with a scouring pad

ADIM 03

Place the metal base plate into the acid solution for about 5 minutes to remove residues left by the scouring pad or fingers. Because this step only removes some loosely adhered residues from the surface, it does not require a long soak.

STEP 04

Take the metal base plate out of the acid solution and rinse it thoroughly with running water for later use. Be sure to use plenty of running water for a full rinse; otherwise, residual dilute sulfuric acid on the surface can adversely affect subsequent enamel firing. Figure 4–16 shows the cleaned metal base plate.

2. Production of Flat-Laid Enamel

2.1 Firing the Back and Base Glaze

During the creation of an enamel piece, the work must undergo repeated high-temperature firings of around 800 degrees Celsius. During high-temperature firing, the enamel glaze melts into a liquid and, due to surface tension, tends to contract. When the contracting forces exceed the adhesion between the enamel glaze and the metal base plate, cracking or even detachment of the enamel layer can occur. To prevent this, we apply enamel glaze to both the front and back surfaces of the metal base plate. With enamel glaze on both sides, the tensile forces produced by shrinkage on each side cancel each other out, greatly enhancing the bond strength between the enamel and the metal base plate.

The glaze on the back of a metal base is called the back glaze. Generally speaking, the thickness of the back glaze needs to be close to that of the front glaze; it may be slightly thinner than the front glaze, but the difference should not be too large. If an enamel piece is not fired with a back glaze, even if the single-sided glaze does not crack or flake off immediately, problems will inevitably appear after some time; even if a back glaze is applied, if it is not thick enough, it still easily cracks. Figure 4–17 shows a copper test plate with glaze fired only on one side; we can observe cracking of the glaze.

Any color of enamel can be chosen for the back glaze. It is best to select glazes with a high melting temperature and that are more durable in firing. For example, do not choose heat-sensitive transparent yellow or transparent red for the back glaze; also, avoid opaque glazes, because opaque glazes generally have lower melting temperatures. After multiple repeated firings, heat-sensitive back glazes can shrink or be lost, and the loss of back glaze directly causes cracking of the front glaze. Some artists like to use the sedimented waste from cleaning glazes as back glaze, but the waste contains various colors of glazes in uncontrolled proportions, and opaque color glazes likely dominate at times. That may not be a big problem for processes that do not require many firings, but for works that require multiple firings, the heat-sensitive colors in the back glaze may shrink or be lost after repeated firings, thereby affecting the front glaze. The small bird brooch shown in Figure 4–18 encountered a similar situation during firing. The back glaze of the bird brooch used waste sediment from cleaning domestically produced cloisonné glazes, which contained a high proportion of opaque glazes. After four firings, cracks began to appear at the tip of the front tail feathers. Examination showed that it was the repeated firing and subsequent shrinkage of the back glaze that caused loss at the edges, which in turn led to cracking of the front glaze. After the back glaze was restored and refired, the cracks on the front healed accordingly. Therefore, when applying back glaze, one should use colorless transparent glaze, that is, the base background color, which has the highest melting temperature among all glazes and is the most durable in firing.

Figure 4–17 Cracking that occurred when there was no back glaze

Figure 4-18 Shrinkage and loss of the back glaze after multiple firings

The specific steps for firing a back glaze are as follows.

ADIM 01

Pat the cleaned metal base dry with paper, with the back facing up, as shown in Figure 4-19.

ADIM 02

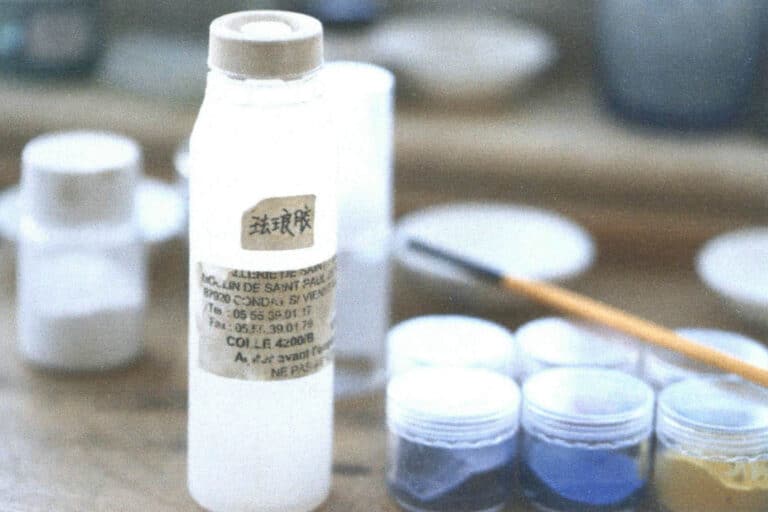

Brush on a very thin layer of enamel glue, as shown in Figure 4-20. Enamel glue is a special adhesive used in the enameling process; it is thin in consistency and cannot be used to bond parts together—its only function is to make the enamel coating adhere more closely to the base. In some enameling techniques, enamel glue is mixed into the glaze. Figure 4-21 shows an enamel glue made in France, appearing as a colorless transparent liquid. There is also a cellulose gum used as a food additive called CMC (Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose), which is a white powder and can also be used as enamel glue when dissolved in distilled water. The purpose of brushing on the glue is to prevent the glaze from peeling and cracking, but it is important to note that only an extremely thin, very small amount should be applied—do not coat repeatedly. Excessive glue can produce bubbles during firing and sometimes affect the glaze’s color, making it yellowish or darker.

Figure 4-20 Brushing enamel glue onto the surface of the metal base

Figure 4-21 Enamel glue

ADIM 03

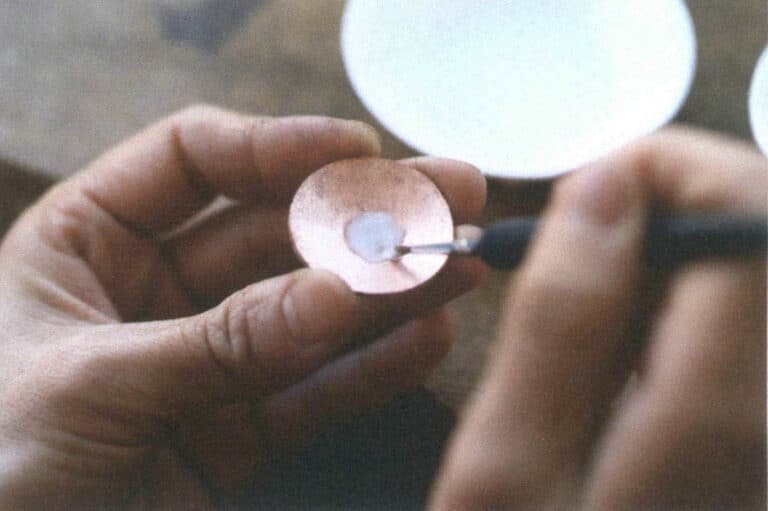

After brushing on a thin layer of enamel glue, you must immediately begin applying the cleaned, colorless transparent base glaze; there is no need to wait for the enamel glue to dry. The glaze used below is the domestically produced cloisonné glaze called “Bright White,” a transparent base glaze specially for copper substrates. The glaze is applied by starting at the center and moving in clockwise circles; Figure 4–22 shows the direction for applying the glaze. This layer of glaze must be both thin and even. Because it is the bottommost base glaze, being too thick will affect the placement of subsequent glazes, so as a rule, it should be applied as thinly as possible. When the glaze is applied very thinly, its thickness must be extremely uniform; otherwise, due to the surface tension of the liquid, the glaze will flow toward the thicker areas when it melts at high temperature. The glaze in the thin areas will be drawn toward the thick areas, making bare spots likely. Figure 4–23 shows the approximate thickness required for this layer of glaze.

When applying the glaze, controlling the moisture content of the glaze is very important. If the glaze is too dry, it is difficult to achieve a smooth, even surface; with an appropriate amount of moisture, the surface tension of the water will naturally form a uniform plane; if the glaze contains too much water, its spread and direction become hard to control, and areas with too little glaze may occur. Figure 4–24 shows the back of a metal test piece fully covered with transparent base glaze.

Figure 4–22 Direction for applying the glaze

Figure 4-23 Applying a thin layer of transparent base glaze

STEP 04

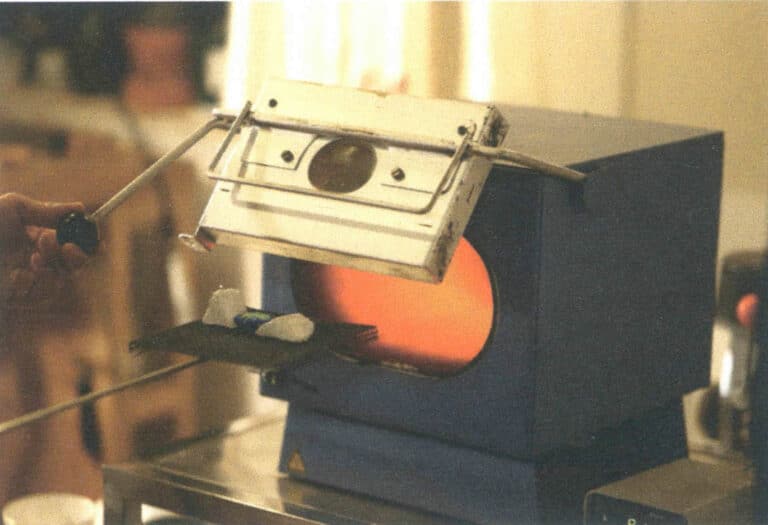

After the moisture in the enamel glaze has completely evaporated, place it into the enamel furnace and set the furnace temperature to 850 °C for firing, as shown in Figure 4-25. Note that after applying the enamel glaze, you must wait until the moisture in the enamel glaze has completely evaporated before putting it into the preheated enamel furnace. Sometimes the surface of the enamel glaze may look dry while there is still residual moisture inside. If the enamel glaze still contains moisture when placed in the furnace, the high temperature will cause the moisture to boil and vaporize instantly, causing the originally smooth enamel glaze surface to burst. Occasionally, on fired pieces, you may see splattered areas where adjacent colors have mixed; this occurs when residual moisture inside incompletely dried enamel glaze boils instantly in the furnace and splashes the surface enamel glaze.

STEP 05

Figure 4-26 shows the copper plate after the back glaze firing is completed. When the cloisonné “bright white” enamel has fully melted, the surface of the copper should be smooth and even, and display a shiny golden color — that is, the unoxidized color of copper. If the copper surface is smooth and even, but the color is not uniformly golden and instead shows localized dark red or brown patches, this indicates the firing was not sufficient; the enamel glaze has melted but has not reached its most fully molten state.

Figure 4-25 Firing the back glaze at 850 °C

Figure 4-26 Back glaze firing completed

After the back glaze firing is completed, a layer of base glaze still needs to be fired before firing the front pattern.

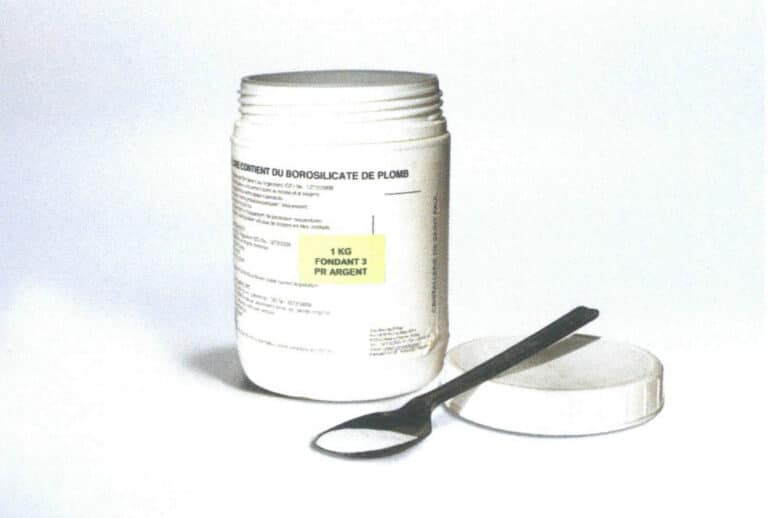

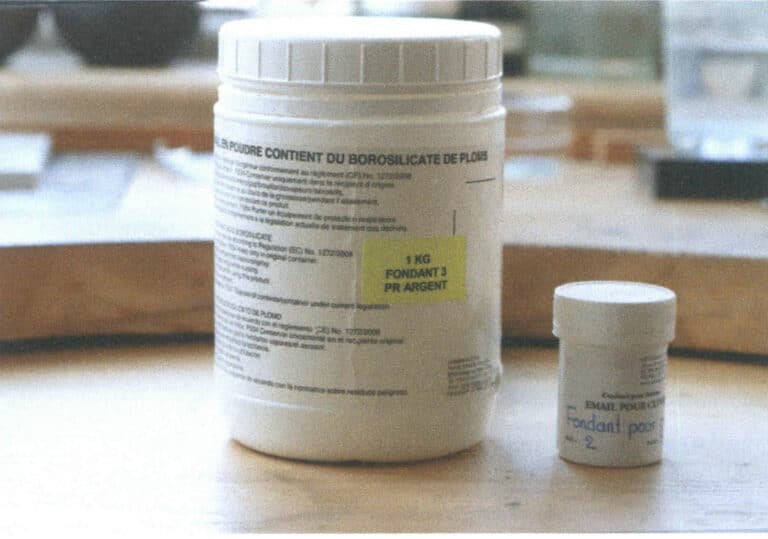

The lowest layer of glaze that is in direct contact with the metal is called the foundational base glaze. The foundational base glaze is a colorless transparent glaze, and different metals require different foundational base glazes. For example, with French glazes, the glaze used as the foundational base glaze is called “Fondant.” Foundational base glaze No. 1 (FONDANT 1) is used on gold substrates, foundational base glaze No. 2 (FONDANT 2) is used on copper substrates, and foundational base glaze No. 3 (FONDANT 3) is used on silver substrates. Figure 4-27 shows the French-made No. 3 silver base glaze; we can see that the No. 3 base glaze is a white powder that becomes colorless and transparent after firing.

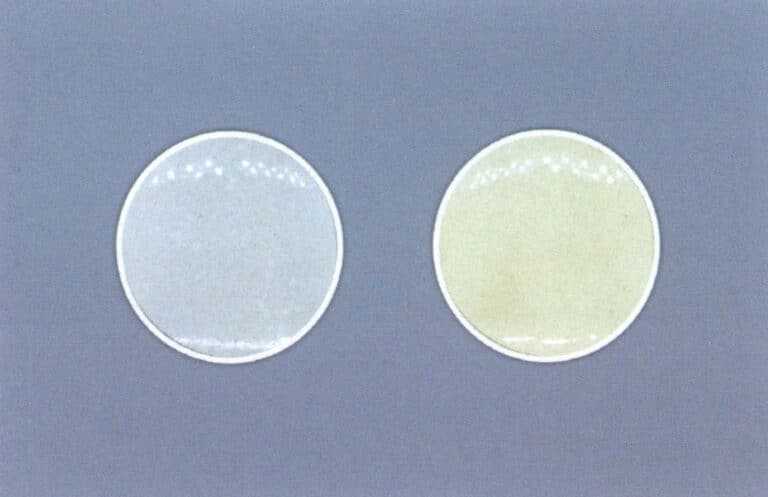

Although called a colorless transparent glaze, it actually has some color tendency and is not completely colorless like water or air. Different brands of foundational base glazes have slightly different color tendencies. Judging from the fired color of silver base glazes, the French foundational base glaze No. 3 is relatively transparent but slightly gray-blue in tone; the domestically produced cloisonné silver base glaze “silver-white transparent” is slightly yellowish; the Japanese cloisonné glaze “silver-white transparent” is closest to colorless transparency. Figure 4-28 shows three pure silver plates fired with transparent base glazes: from left to right, they are French foundational base glaze No. 3, the domestic cloisonné glaze “silver-white transparent”, and the Japanese cloisonné glaze “silver-white transparent”; it can be seen that the Japanese “silver-white transparent” is the most transparent.

Figure 4-27 French FONDANT No.3 base glaze

Figure 4-28 Comparison of silver base glaze effects from different brands

The melting and firing temperatures of transparent basic base glazes are the highest among all glazes, and they are the most firing-resistant. They are generally fired at a kiln temperature of 850 °C. When the firing temperature is insufficient, the color results will be affected. For example, the French basic base glaze No.3 often turns yellowish if fired below 840 °C. Figure 4-29 shows a comparison of French basic base glaze No.3 fired at 850 °C and at 830 °C; as can be seen, the right-hand test piece was fired at an insufficient temperature and therefore appears yellowish.

The main composition of the basic base glaze is very similar to borax, so it has the effect of preventing metal oxidation. After firing a layer of base glaze, the colors applied above that glaze become more vivid. Especially when enameling on a copper substrate, it is essential to first fire a layer of transparent base glaze; otherwise, all colors will look blackened and dull. In the test pieces shown in Figure 4-30, one can see the difference between firing a transparent base glaze and not firing it. The same three colors of glaze (from top to bottom are Cloisonné glaze pink, French opaque yellow No. 76, French transparent blue-green No. 46), with the left half of each test piece having a transparent base glaze fired beneath, and the right half having no transparent base glaze fired beneath. It is clearly visible that the right side’s color is darker; this final color difference is precisely caused by the copper substrate on the right becoming oxidized and blackened because no base glaze was fired on it.

Figure 4-29 Comparison of effects of French basic base glaze No. 3 fired at different temperatures

Figure 4-30 Comparison of color effects with and without base glaze

2.2 Making the Front Pattern

After firing the back glaze and the base glaze, you can begin making the front pattern.

As the name implies, the flat-laid enameling process requires laying the enamel very evenly, because there is no polishing step afterward; whether the enamel glaze is laid flat directly determines the final appearance of the piece. In the production of flat-laid enamel works, the most important step is firing the front pattern.

First, you need to choose a design suitable for this technique. As mentioned earlier, the flat-laid enameling process is suitable for firing large areas of color blocks or relatively simple patterns; it is not well suited to producing intricate, dense designs or motifs—such as fine, clear curves or straight lines, or curled and interlaced patterns. However, if the maker has a precise technique and enough patience, quite detailed images can still be achieved; Figures 4-31 and 4-32 are two good examples. The piece shown in Figure 4-31 uses the flat-laid enameling process to achieve clearly defined, densely distributed small color blocks; the piece in Figure 4-32 uses the flat-laid process to produce straight, clear lines and a well-executed color gradient. When creating works with the flat-laid enameling process, achieving densely arranged small color blocks, linear patterns, and color gradients is somewhat difficult—the main challenges lie in the application of the enamel glaze: how to make two adjacent colors join tightly and evenly, and how to create a clear, neat boundary between neighboring colors. These requirements place high demands on the operator’s technique and familiarity with the properties of the enamel glaze.

Figure 4-31 Flat-laid enamel piece "Flower of Dreams"

Figure 4-32 Flat-laid enamel piece "Wofeng Wuwangcao"

Once the design has been finalized, production can begin. The specific steps for firing the front-side design are as follows.

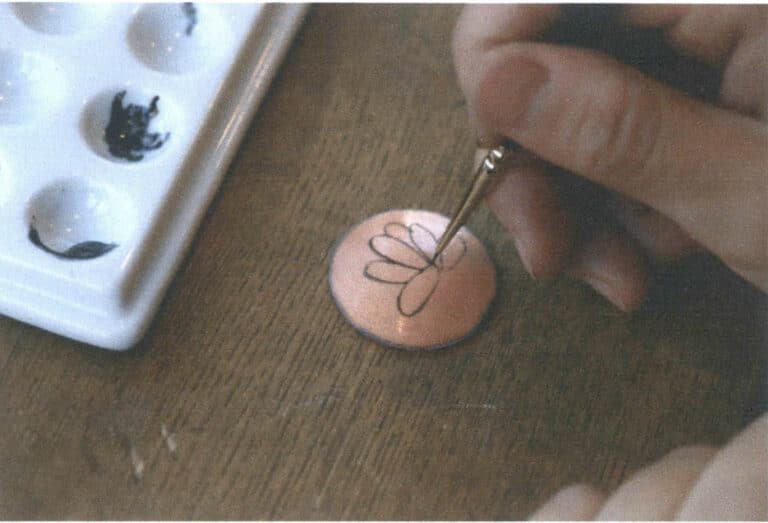

ADIM 01

After firing the back glaze and base glaze, use painting enamel (paint enamel) to draw lines on the fired base glaze on the front of the piece, as shown in Fig. 4-33. The purpose of this step is to paint the design onto the transparent base glaze; in the next step, these painted lines will serve as reference guides for filling in glazes of different colors. The upper layers of glaze will ultimately completely cover these lines, so the lines painted in this step will not be visible on the finished surface. When painting, keep the lines as thin and fine as possible to avoid creating unevenness in the overlying glazes. After the lines are painted, set the kiln temperature to 770°C and fire; after firing, the design lines will be fixed to the base glaze. Inspect after firing: the lines should appear integrated with the glaze, as shown in Fig. 4-34. If the lines look as if they are floating on the glaze surface, that means the painting enamel has not fully melted and needs to be fired again.

Figure 4-33 Drawing lines

Figure 4-34 Firing and fusing

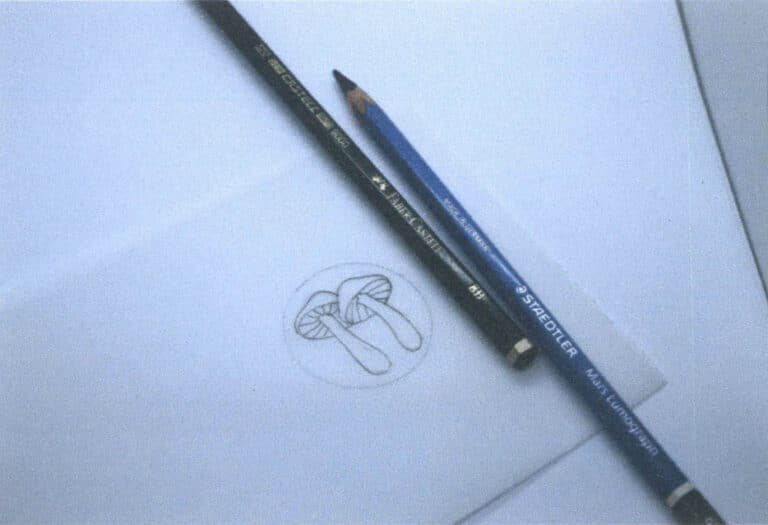

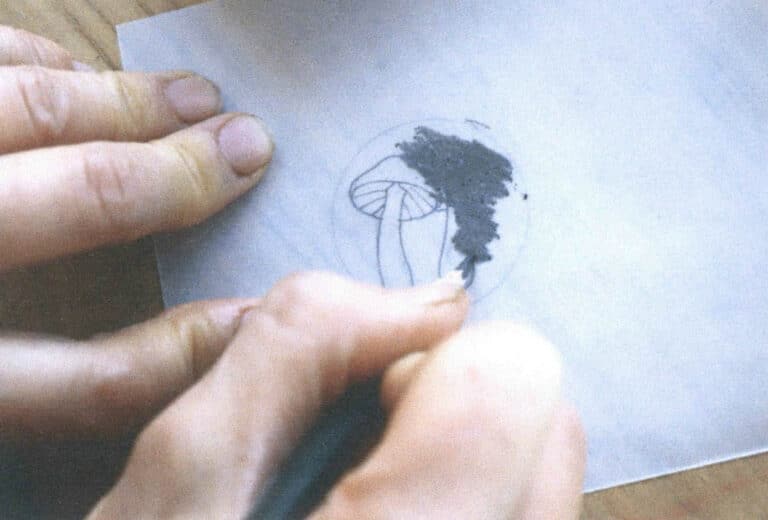

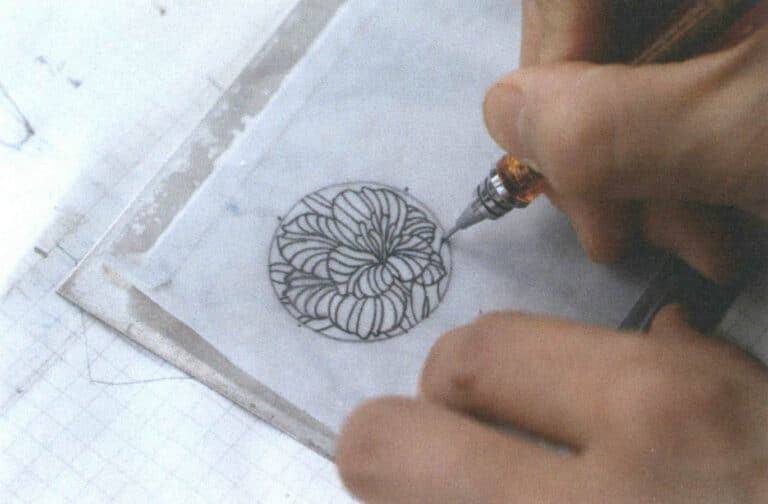

There is an easier way to trace pattern outlines: use a regular drawing pencil to transfer the design. Choose a high-quality drawing pencil, such as Staedtler or Faber-Castell, and use translucent tracing paper, as shown in Figure 4–35. Note that charcoal pencils should not be used for tracing on enamel pieces.

First, transfer the design onto the tracing paper; on the back of the pattern, thoroughly shade all areas that have lines on the front with an 8B pencil, as shown in Figure 4-36.

Figure 4–35 8B pencil and tracing paper

Figure 4–36 Shading the back of the tracing paper with an 8B pencil over the areas that have lines on the front

Then place the tracing paper over the piece whose back and base glazes have been fired, making sure to align the design on the tracing paper with the position of the piece below, as shown in Figure 4-37.

Use a pen with a relatively hard tip to retrace all the lines along the contours on the front of the tracing paper, as shown in Figure 4-38; at this point, the pencil dust on the back of the paper will be transferred onto the piece. The pen used for tracing can be a metal scribing pen from metalworking tools, a technical pen, or a fine ballpoint — in short, it should be hard and pointed to produce precise lines. Here, a metal scribing pen is used.

Figure 4-37 Aligning the tracing paper with the piece beneath

Figure 4-38 Transferring the design

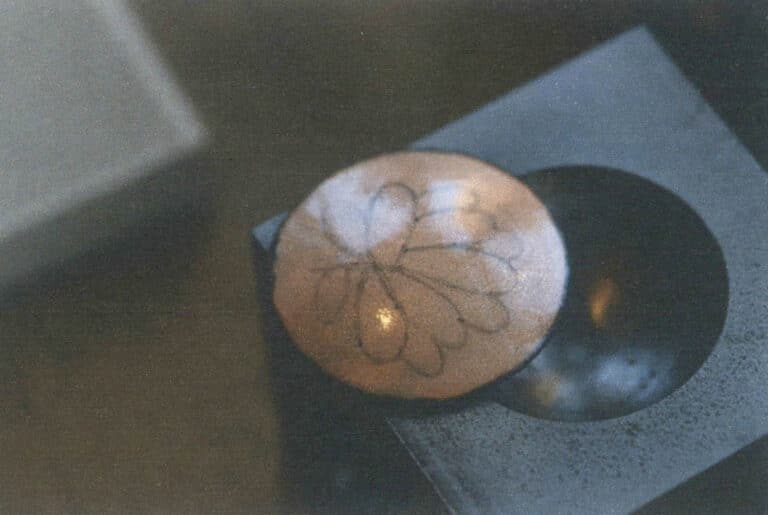

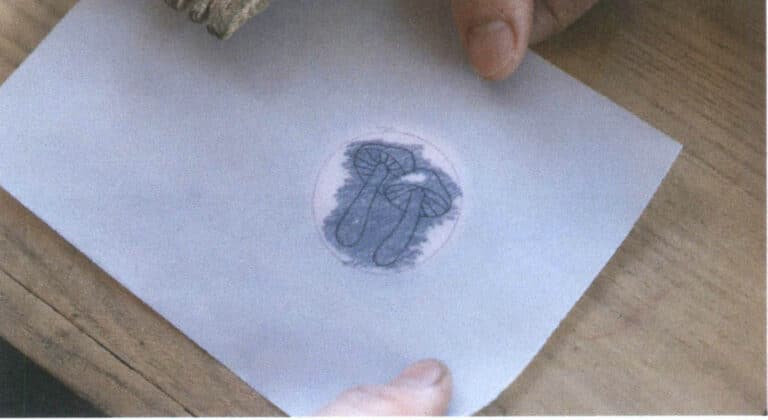

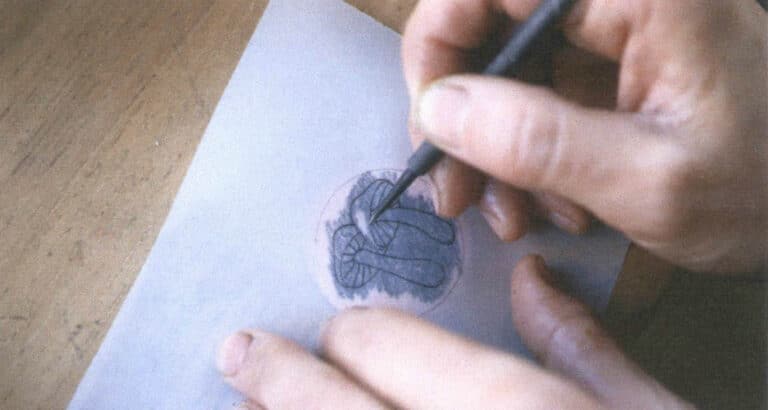

Figure 4-39 shows the design pattern successfully transferred onto the surface of the piece. The kiln temperature was set to 760°C for firing. The operating method is the same as when using painted enamel glazes, so it will not be repeated here.

The pencil powder can fuse with the glaze during firing, becoming a reference boundary for the next glazing step and not adversely affecting the glaze. The traced pencil lines become lighter after firing, so when tracing, you need to press relatively deeply to ensure clear contour lines remain after firing. Figure 4-40 shows the surface of the piece after firing, where you can see that the pencil lines are much lighter than before firing.

Figure 4-39 The traced pattern contours on the piece

Figure 4-40 The pencil lines are lighter after firing

ADIM 02

Select glazes according to the design pattern, grind and wash all chosen glazes, and put the washed glazes into small-capacity containers for later use, as shown in Figure 4-41. Each container should be clearly labeled with the glaze color number or name—this is a very important detail. We use multiple glazes at the same time during each session; without labeling the color number or name on the containers, glazes with similar colors can easily be confused. Once confused, the maker cannot control the glaze colors and cannot ensure the piece will fire to the intended colors. In addition, all leftover enamel glazes can be stored and reused; if the color number or name is not labeled, it will be difficult to tell which glaze is in each container when reused.

ADIM 03

According to the pattern lines fired in STEP 01, fill different colored glazes as required by the design. Place all the colors in sequence at one time, ensuring they are even and level; especially at the boundary between two adjacent colors, no depressions should form. The overall thickness of this layer of glaze should be much greater than that of the back glaze and base glaze, as shown in Fig. 4-42. Controlling the moisture when applying the glaze is crucial: if there is too little moisture, it is difficult to spread the glaze smoothly, while too much moisture makes it hard to control the glaze boundaries. The right balance can only be accurately mastered through continuous practice and training.

STEP 04

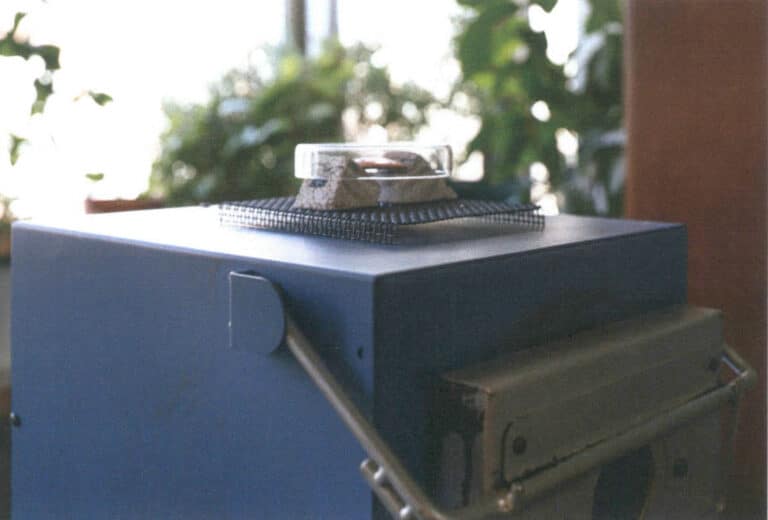

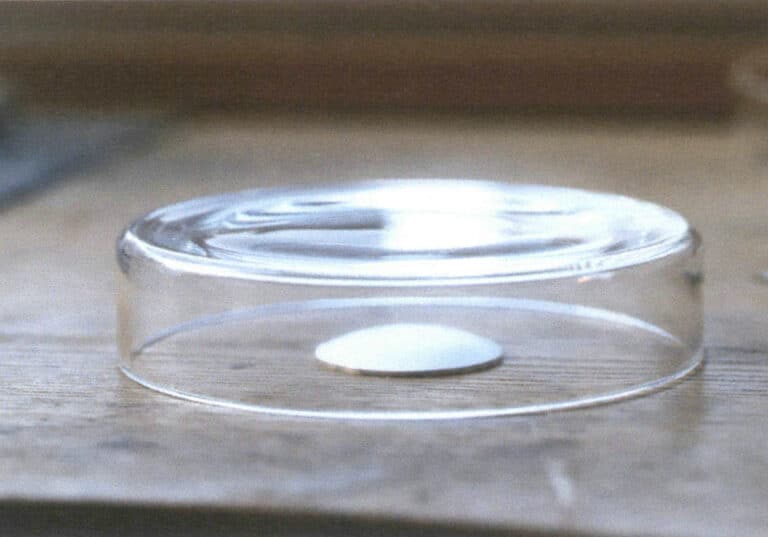

Place the glazed piece in a clean environment to air-dry the moisture from the glaze, as shown in Fig. 4-43. Thoroughly drying the moisture from the glaze is to avoid wet glaze bursting in the kiln. During the drying process, take care to prevent dust or debris from falling on the surface of the piece; you can cover the piece with a glass dome.

STEP 05

Fire at a set temperature of 810°C, as shown in Figure 4-44. When firing in the kiln, pay attention to removing the piece promptly once the temperature reaches 810°C, because most of the enamel glaze used in the flat-laid enamel technique are opaque; opaque enamel glaze have lower melting and firing temperatures and are not durable under high heat. If the kiln temperature is too high, the transparent base glaze underneath can flow up to the surface, especially when the upper glaze layer is thin, so be sure to take the piece out of the kiln in time.

STEP 06

Figure 4-45 shows the completed fired piece.

Precautions

(1) Glazed pieces must be allowed to dry completely until all moisture in the glaze has evaporated before being placed in the kiln for firing. Otherwise, residual moisture in the glaze will reach the boiling point the moment it enters the kiln, causing the glaze powder to spatter. Adjacent glazes often mix during firing when their moisture has not fully dried. This splattering-type mixing between neighboring glazes is especially common when producing flat-laid enamel pieces laid out flat, because most glazes used in this process are opaque, so even a small amount of color contamination is very noticeable. The test piece shown in Figure 4-46 was put into the kiln without drying after glazing, and severe glaze bursting can be seen. The test piece shown in Figure 4-47 was fired before the glaze had completely dried, and splattering between the black and white glazes can be observed.

Figure 4–46 Glaze exploded in the kiln because it had not dried

Figure 4–47 Glaze splattering caused by not being completely dry

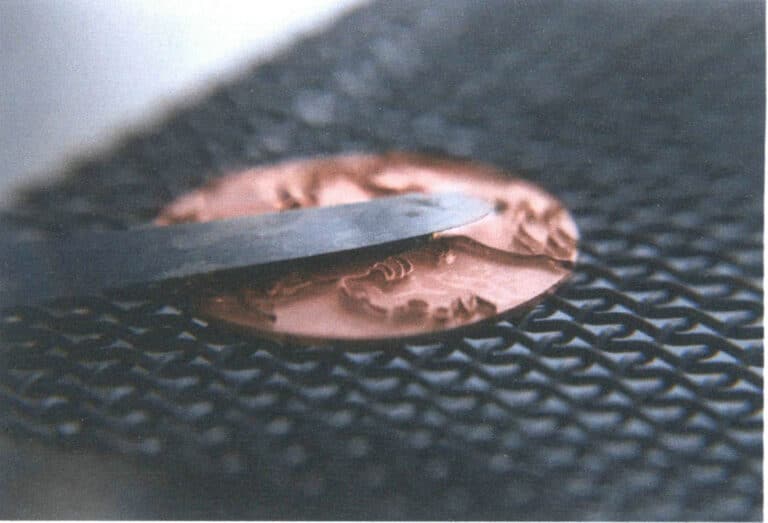

(2) Because flat-laid enamel pieces are not polished after firing, the glaze must be applied very evenly so that the result after firing is good. The maker can, with skilled technique, smooth the glaze during the application stage, or after laying down the glaze fully, use a tool to level it. Figure 4-49 shows the process of leveling the glaze surface with a flat wax-carving knife. Before leveling, absorb the moisture from the glaze with a paper towel, then use the flat side of the carving knife to push the glaze from thick areas toward thin areas with force until the glaze thickness across the entire piece is completely uniform.

(3) At the junctions between different colored glazes, the thickness must be consistent and the transition smooth. Pay particular attention to ensure the border between adjacent colors does not sink; otherwise, during high-temperature firing, the glaze will be drawn from the thin areas toward the thick areas, making the thin areas even thinner and sometimes exposing the color of the base glaze. In addition, the colored layer of glaze needs to be much thicker than the base glaze; otherwise, exposure of the base layer is also likely.

Figure 4-50 shows the normal condition of glaze at a junction, where the thickness of the colored glaze layer and the condition at the boundary between the two colors can be observed. The thickness at the intersection of two adjacent colors must be the same to ensure a flat surface after firing. Figure 4-51 shows a condition where the glaze at the color junction is too thin, and the base is exposed; Figure 4-52 shows the colored glaze layer is too thin, resulting in the base glaze being exposed after firing.

Figure 4-50 Normal condition of glaze at the junction

Figure 4-51 Glaze at the junction is too thin, causing exposure of the body

Figure 4-52 Color layer glaze too thin, causing exposure of the body

Copywrite @ Sobling.Jewelry - Özel takı üreticisi, OEM ve ODM takı fabrikası

Section II Production Of Cloisonné Enamel

From the perspective of craft operations, cloisonné enamel is one of the more complex enamel techniques presented in this book. Unlike the flat-laid enamel introduced in the previous chapter, most cloisonné works cannot achieve the desired effect with a single filling and firing; they require multiple applications of enamel and repeated firings, as well as polishing and refiring steps. Because of the technique’s characteristic— the combination of filling material and wires greatly enhances the adhesion of the enamel to the metal—this method allows for the firing of relatively thick enamel layers on metal. To achieve better color results and reduce bubbles within the enamel layers, makers often choose to apply enamel and fire repeatedly. Compared with other enamel techniques, cloisonné is more material- and time-consuming. Still, when the operator is skilled, this technique is highly controllable and well-suited to producing complex, rich effects. Finished cloisonné works are delicate, splendid, and highly decorative; enamel artists have long favored them and are among the most common enamel objects.

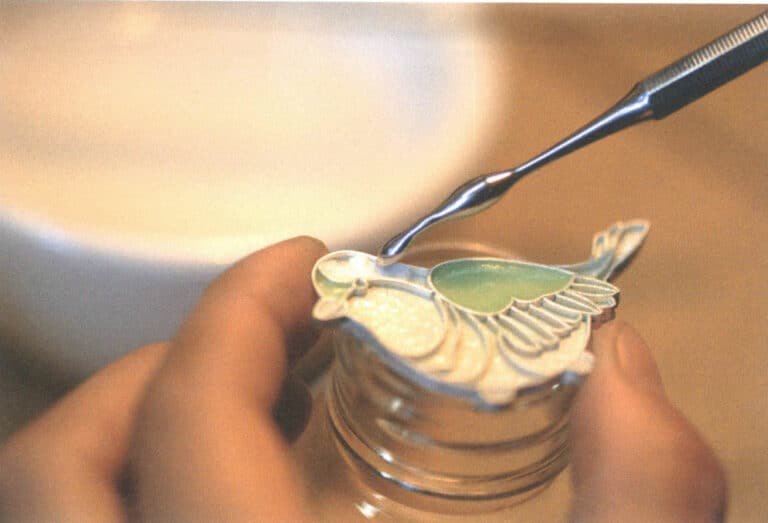

Figure 5-1 shows the situation of applying the second layer of enamel glaze during the production of a filigree enamel piece. The production process of cloisonné enamel includes preparing the metal materials, making the wires, abrasives, fillers, firing, and polishing; this chapter will introduce the specific operating methods of each procedure in sequence.

1. Preparation of Metal Materials

1.1 Cleaning and Doming Treatment of the Metal Base Plate

Section I explained that to prevent metal deformation and to ensure a firmer bond between the metal and the enamel glaze, the metal base must be cleaned and domed before firing. The same pre-treatment of cleaning and doming the metal base is also required in the production process of cloisonné enamel.

The specific procedure is the same as previously described: find a suitably sized concave mold and press the metal base into it to form a uniformly slight convex shape, increasing the strength of the metal base and reducing deformation during firing. In the example in this chapter, a sterling silver base is used.

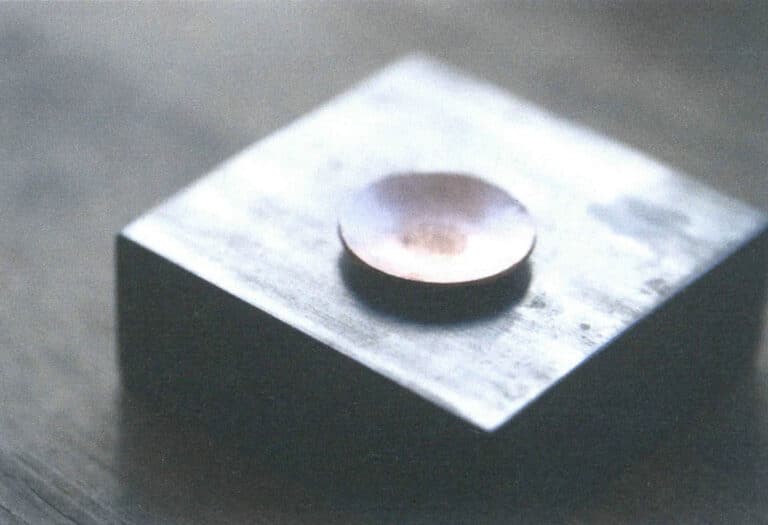

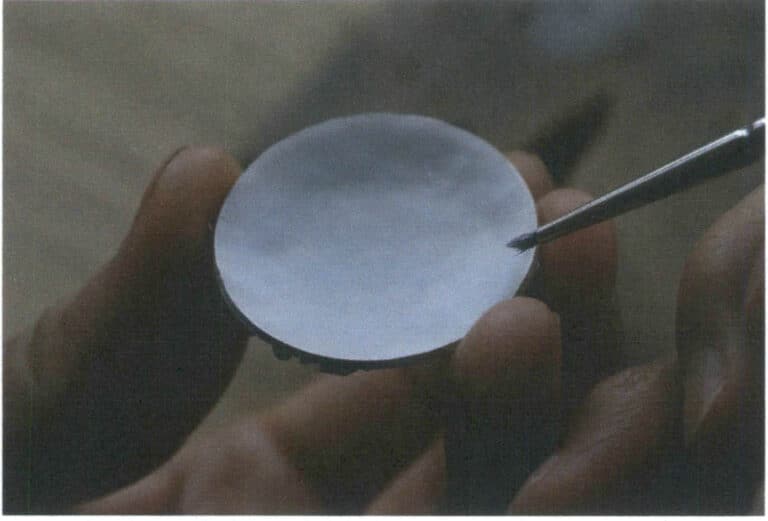

Immerse the prepared slightly domed sterling silver base in a dilute sulfuric acid (or dilute nitric acid) solution with a concentration of 30%~50% for 10~15 minutes, until the metal surface is completely clean. The silver base shown in Figure 5-2 has a snow-white matte appearance, which is a sign that the silver surface is very clean.

Remove the silver plate from the acid, rinse repeatedly with running water, and let the cleaned metal base air-dry or dry it with paper towels for later use. Figure 5-3 shows the cleaned silver base ready for use, the silver wire for the cloisonné, and the transparent ground enamel after grinding and cleaning.

Figure 5-2 The silver base appears matte after pickling

Figure 5-3 The cleaned silver base, silver wires, and transparent base glaze

Notes

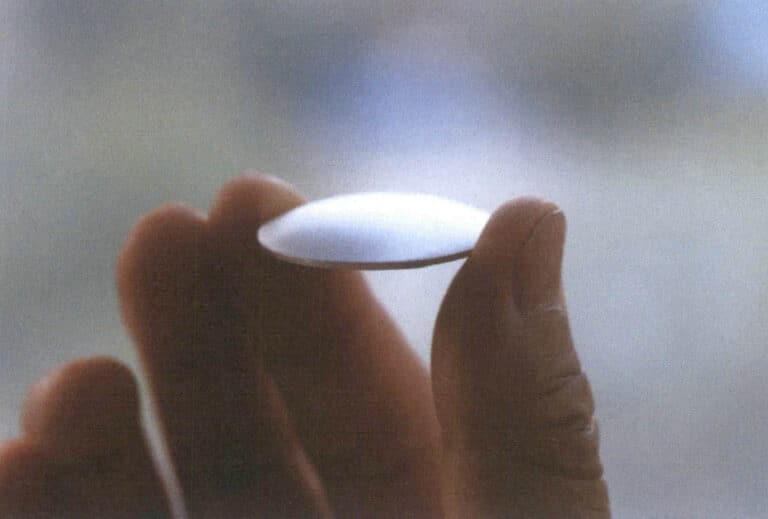

(1) To avoid oils and sweat from fingers remaining on the metal surface and affecting the bond between the glaze and the metal, metal substrates treated with acid must not be touched on their surface by hand. When handling, support the edge of the metal substrate with your fingers, as shown in Figure 5-4. This posture should be used when picking up the piece until the final firing is completed; during production, avoid direct contact between fingers and the surface of the work. Enameling requires a very high level of cleanliness throughout the operation—materials, tools, and even the surrounding environment must be very clean. Any bit of oil or dust at any stage can produce visibly noticeable effects on the final appearance of the piece.

(2) If the metal base plate washed with clean water is dried by airing, it can be covered with a glass hood as shown in Figure 5-5 to prevent dust in the air from falling onto the metal surface.

Figure 5-4 Method of handling the cleaned metal base plate

Figure 5-5 Dustproof glass hood

1.2 Preparation of Metal Wires in the Cloisonné Enameling Process

In cloisonné works, metal wires function similarly to lines in painting. Thin metal wires accurately and distinctly divide different areas between the enamels, and can convey soft, strong, quiet, or lively lines according to the artist’s intent, producing a highly decorative effect. It is precisely the presence of the “wire” that clearly distinguishes the cloisonné technique from other enameling techniques. One could say that the “wire” is the most important characteristic of cloisonné.

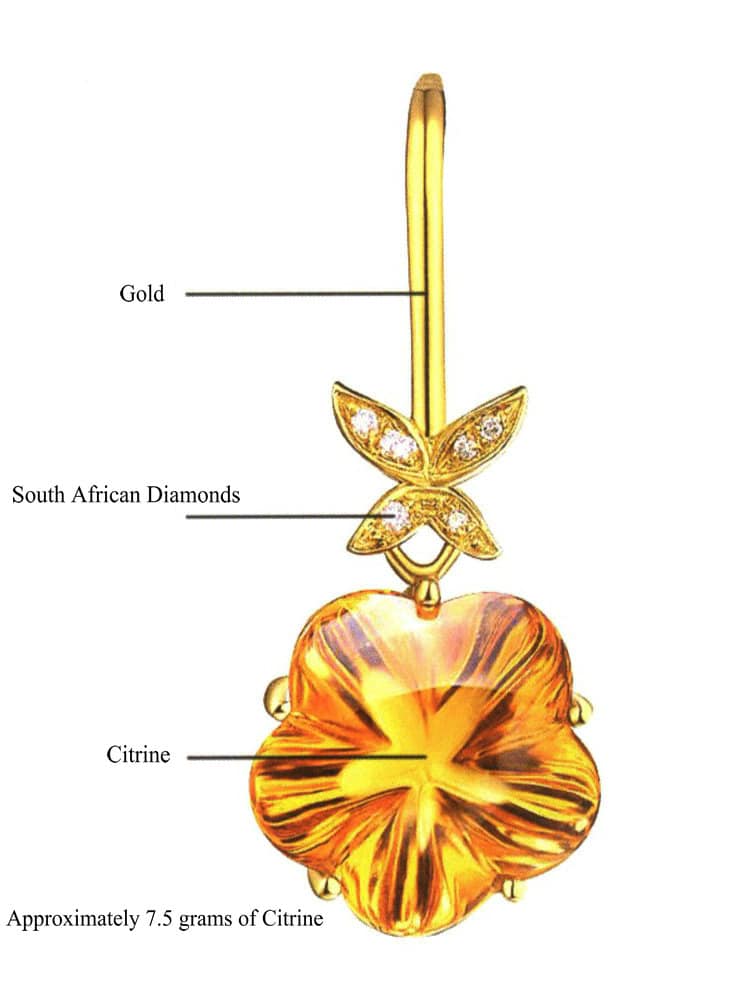

First, when creating a cloisonné piece, one must decide what material to use for the metal base plate and what material to use for the metal wires. On copper, silver, or gold bases, copper, silver, or gold wires can be used; in theory, they can be mixed freely. For example, firing gold or silver wires on a copper base is common, and in fact, firing copper wire on a gold base is also possible, though almost no one does that. Because once the work is finished, only the enamel and the wires are visible on the surface—the metal base plate does not show—many enamel artists choose to lay silver or gold wires on a copper base or gold wires on a silver base to achieve optimal appearance while saving costs. Additionally, if silver or gold wires are used, no black oxide layer forms during firing, so the pickling process after each firing can be omitted, shortening production time and reducing labor costs. Figure 5–6 shows an enameled cloisonné pendant by American enameler Don Viehman; this piece was made by laying gold wire on a silver base and firing it. The specific choice of base and wire materials entirely depends on the maker’s design intent; different materials can be selected to meet different needs.

Secondly, it should be noted that in the making of cloisonné enamel, it is best to use metal wires of high purity, for example, pure gold, pure silver, or pure copper wires. High-purity metal wires possess the flexibility required by the cloisonné technique; they can be bent and adjusted repeatedly without breaking.

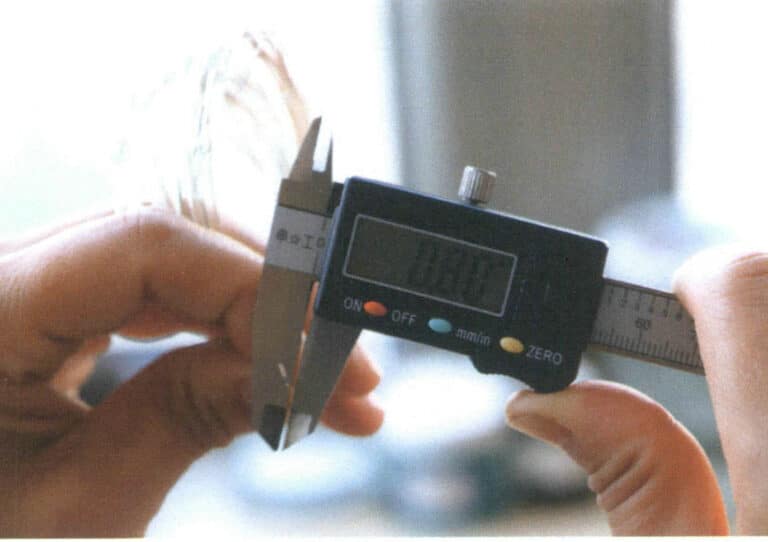

As for the size of the metal wires used in cloisonné enamel, there is no fixed rule; it entirely depends on the needs of the work and the maker’s preference. Most cloisonné enamel works are made using flat wire. The wire’s dimensions include thickness and width, where thickness refers to the side measurement of the wire — that is, the part that is ultimately visible on the surface. In the production of cloisonné enamel watch dials, because the dial itself is very small, the wire thickness used is only 0.04 millimeters. For artistic enamels, there is comparatively more freedom: the artist can decide the thickness of the metal wire according to the work’s size and personal style. For works of the same size, if a strong, powerful style is desired, thicker wire may be chosen; if the pattern is intricate and delicate, thinner wire may be chosen. Figures 5–7 show a cloisonné enamel decorative painting by Georgian enamel artist Dato Jamrishvili; in the image, you can see that the artist used silver wires of different thicknesses, with thicker wire for outer contours and thinner wire for facial and detail areas. The width of the metal wire refers to the front dimension of the flat wire, and this dimension determines the thickness of the enamel glaze that can be placed. Wire width depends on the artist’s color requirements: if a high color saturation is required, meaning multiple firings and layers, a wider wire will be needed, which increases the distance from the base plate to the top of the wire and therefore provides more space to hold enamel; conversely, a narrower wire can be chosen. Figure 5–8 shows the thickness and width of silver wire: the wire’s thickness determines the final line thickness visible on the surface, while the wire’s width determines the distance from the metal base to the enamel glaze surface, i.e., how thick a layer of enamel glaze it can accommodate.

Figure 5–7 Cloisonné enamel decorative painting

Figure 5–8 Thickness and width of silver wire

The metal wire used for the cloisonné examples in this book is flattened pure silver wire with a thickness of 0.1 mm and a width of 0.8 mm, as shown in Figure 5-9.

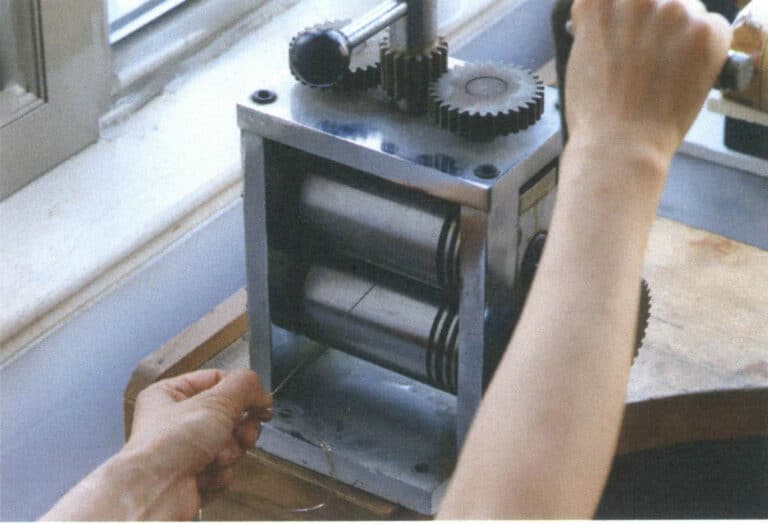

The metal wire used for cloisonné generally needs to be prepared by oneself; you can make a batch to keep in reserve. First, use a wire-drawing plate to obtain round wire of the appropriate diameter, then press the round wire into flattened wire of the suitable thickness in a rolling mill.

When flattening the round metal wire in the rolling mill, first adjust the gap between the two rollers to a size that clamps the wire. Turn the handle with one hand while using the other hand to pull the remaining round wire straight with force. Be sure to turn the handle slowly and evenly; otherwise, the wire may bend or deform during flattening. Figure 5-10 shows the situation when flattening round wire with the rolling mill; note that the left hand must pull the silver wire straight with force.

Figure 5-9 The silver wire used in this book has a thickness of 0.1 mm and a width of 0.8 mm

Figure 5-10 Preparing silver wire with rolling mill

Notes

(1) The diameter of the round wire before flattening should be slightly smaller than the required width of the flat wire, because pure silver wire is very soft and will elongate during flattening; however, it should not be much smaller than the required width. During pressing in the rolling mill, the metal wire mainly elongates longitudinally and expands less laterally. Generally speaking, if a flat wire 0.8 mm wide is needed, a round wire with a diameter of 0.7 mm can be flattened. Figure 5–11 shows a comparison between the round wire and the flattened flat wire; it can be seen that the width of the flattened wire is only slightly larger than the diameter of the round wire.

(2) Due to the excessively high speed of electric rolling mills, using a manual rolling mill allows for better control, thus avoiding deformation of the silver wire during the flattening process. As shown in Figure 5-12, the wire in the image became deformed because the speed was not properly controlled and the wire was not kept taut during flattening; this section of wire can only be discarded.

Figure 5–11 Comparison of round wire in millimeters and flattened ribbon wire

Figure 5–12 Wire deformed during pressing

2. Production Of Cloisonné Enamel

2.1 Wire Twisting

Tools used for wire shaping can be tweezers, round-nose pliers, or any tool capable of bending metal wire; in addition, a pair of scissors or cutting pliers capable of cutting the metal wire is required.

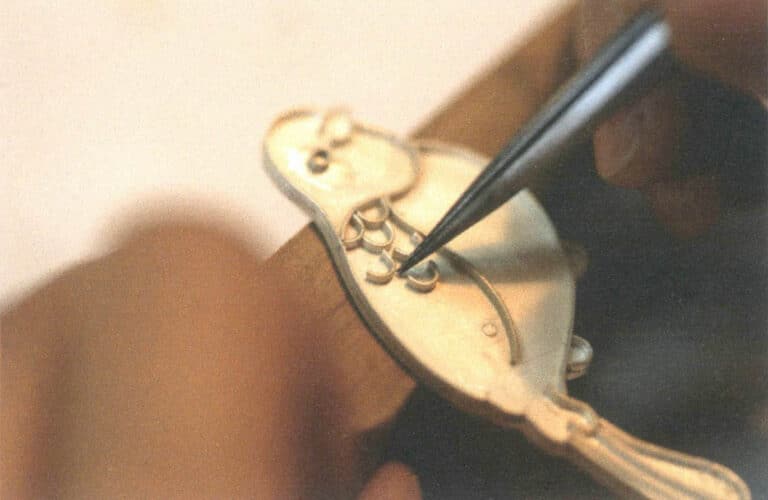

In China, the wire-twisting step in filigree and cloisonné industries uses specially made wire-shaping tweezers. These tweezers have thick arms and sharp tips, which can both easily bend and deform metal wire as required and perform very precise, detailed operations. The black tool on the left in Figure 5-14 is a traditional wire-twisting tweezer used in filigree craft; it is made of steel and coated with a layer of black protective paint. Tweezers purchased from tool shops need the tips filed finer with a rasp until they meet the user’s requirements; note that the sides of the tips should be filed smooth and rounded so that smooth lines can be produced during wire twisting without damaging the soft wire. After filing, finish by sanding with 280-grit sandpaper.

In the making of traditional Chinese filigree work, the scissors used to cut metal wire are also specially made filigree scissors. Their characteristic is that the handle part of the scissors is very wide for a firm grip, while the cutting blade portion is very short to facilitate fine operations. Figure 5-15 shows two filigree scissors.

Figure 5-14 Wire-twisting tweezers (left)

Figure 5-15 Filament scissors

The specific steps for wire twisting are as follows (using pure silver wire as an example).

ADIM 01

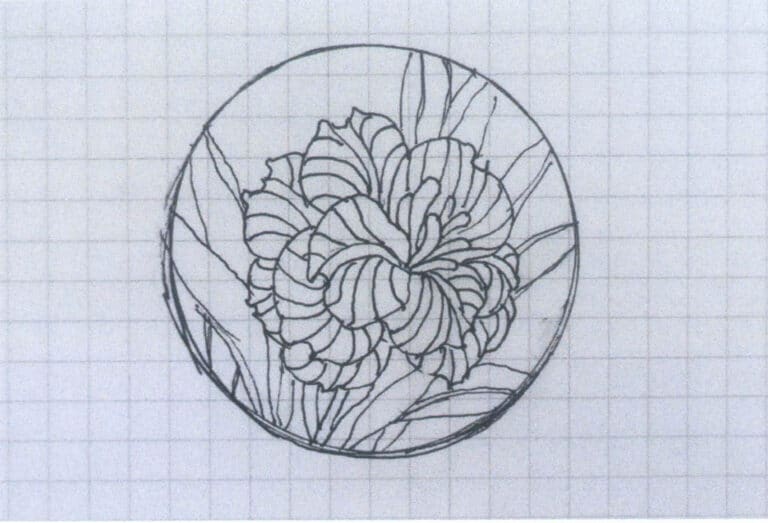

Prepare a 1:1 line drawing of the design on a sheet of white paper. The line drawing mentioned here differs from the design drawing, because the subsequent cloisonné work will be carried out entirely based on the lines in this line drawing. Therefore, if you want to realize the design as perfectly as possible, this line drawing must be one hundred percent accurate, and all lines in it must be precise single lines without any uncertainty or ambiguity. Figure 5–16 shows the design drawing, and Figure 5–17 shows the formal 1:1 line drawing being traced; comparing the two reveals the difference between the design and the formal line drawing.

Figure 5–16 Design drawing

Figure 5–17 1:1 line drawing

ADIM 02

Cut off a piece of the prepared silver wire about 15 cm long to make it easier to handle, as shown in Figure 5-18. Since wire twisting is a precise operation that requires the maker’s full concentration, holding the entire spool of silver wire in your hand not only interferes with fine hand movements but may also inadvertently damage the remaining wire during the process, for example, by creasing, twisting, or knotting it. To be able to shape smooth curves, the spare wire should be kept as straight and neat as possible, so cutting only what you need is a better approach.

ADIM 03

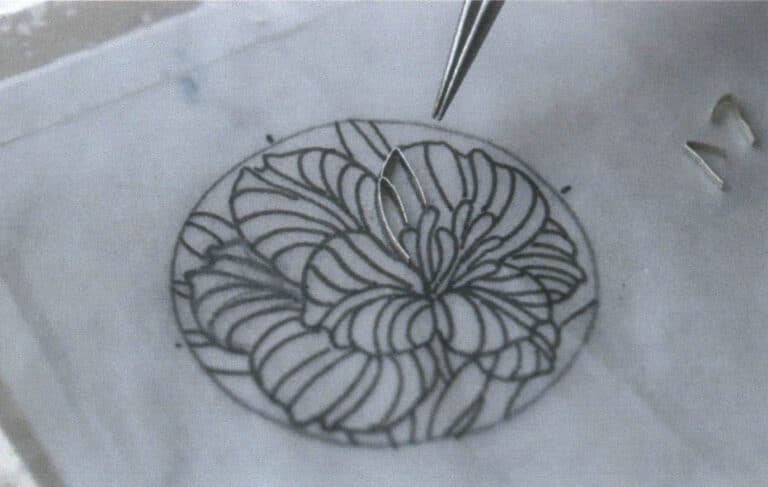

Divide the design on the paper into sections, and bend the silver wire to the required shape according to one section of the design. Estimate how long the wire needs to be for this portion of the curve, cut it off, and use shaping tweezers to refine the wire until it fully matches the design, as shown in Figure 5-19. Note that each segment should not be too long, because excessive length can cause the wire to deform or not lie flat. In addition, when placing the wire, the lines must form completely closed areas between them to prevent the enamel glaze from leaking during enameling, as shown in Figure 5-20.

Figure 5-19 Twisting the wire

Figure 5-20 Placing Wire

Notes

(1) Unless there are special requirements, metal wires do not need to be annealed in advance. Annealed metal wire becomes too soft, and the lines pinched out appear weak and ineffectual.

(2) When cutting metal wire, try to ensure the cut is perpendicular to the wire; only then will the joint be tight when the segmented wires are fitted together, achieving the goal of separating different enamel glaze areas. If the wire joints are not tight, the enamel glaze will flow into other areas when melted, causing color mingling. As can be seen in Fig. 5-21, if silver wire is not cut perpendicularly, although the two wire ends may look fine from the front when fitted together, however, a gap left at the bottom. Once the glaze melts, it will certainly seep out from beneath the silver wire, causing color mixing between adjacent areas.

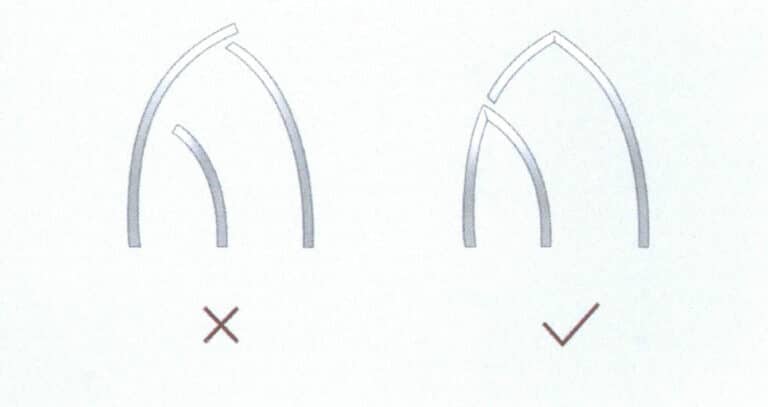

(3) When the design contains straight lines or short arcs with small curvature, try to connect them with adjacent lines or increase their curvature. Figure 5-22 shows a schematic: short wires placed alone risk collapsing, and can each be combined with neighboring wires to form an angled wire. Because straight lines or short arcs cannot stand upright on the surface by themselves, even if they are forced to stand in the wet glaze, they will collapse during firing. Figure 5-23 shows silver wires that have collapsed into the glaze during firing.

Figure 5-22 Reasonable combinations between each wire segment

Figure 5-23 Silver wires bent over in the glaze during firing

(4) Cut metal wires should be arranged on a sheet of paper beside you in the order of the pattern, as shown in Figure 5-24. Especially for more complex designs, sometimes double-sided tape is applied to the paper, and the cut wires are gently placed on the tape in sequence; this prevents all the wires from becoming mixed together and indistinguishable.

2.2 Filling Material and Firing

Once all the lines in the pattern have been “twisted” into place, you can prepare the filling material and proceed to firing.

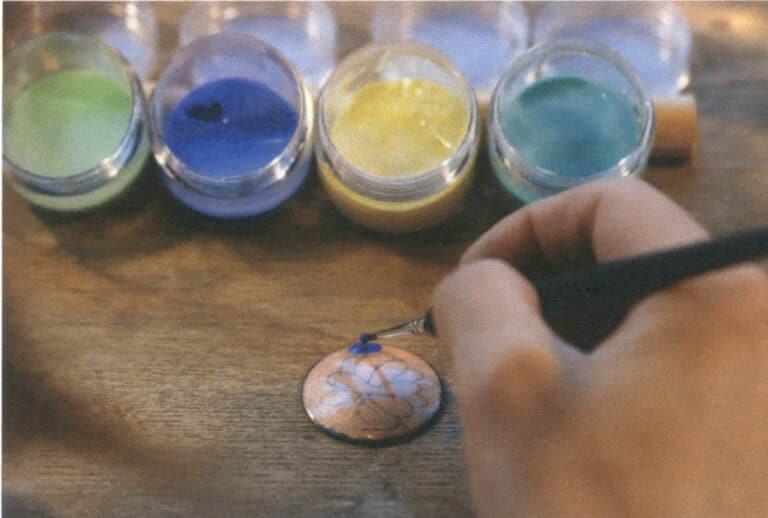

Select the glazes in the required colors, and clean and grind all the glazes following the methods described above. Place the cleaned and ground glazes in small porcelain dishes or small-capacity containers for later use, and be sure to label the different glaze color codes on the containers, as shown in Figure 5–25.

In the previous chapter’s flat-laid enameling technique, the first firing was for the back glaze. When firing cloisonné, you can choose to fire the front first—that is, the side with the cloisonné pattern. Because the metal wires that form the pattern help the glaze bond more firmly to the metal base, similar to the role of rebar in construction, this can prevent cracking or peeling when firing glaze on only one side. This is especially true when enameling on a silver base, because silver is relatively soft, glaze fired on a single side is particularly prone to cracking or even falling off, whereas the metal wires embedded in the glaze can reinforce the structure and greatly increase the strength of the bond between the glaze and the metal base.

There are two methods for fixing the formed wires onto the metal surface. In China, the more common approach is the traditional method used in Jingtailan (Chinese’s Cloisonné) craftsmanship: following the pattern design, use Bletilla adhesive to stick the metal wires to the metal surface, sprinkle powdered flux for soldering, perform the soldering, then pickling, and finally fill and fire. Figure 5–26 shows the situation of soldering the wires onto the body during the Jingtailan production process.

In the cloisonné enamel example in this article, neither soldering nor glue is used to secure the metal wires; instead, the metal wires are placed directly into the wet glaze, meaning the filling and the wire placement are done simultaneously.

The specific steps for filling and firing cloisonné enamel are as follows.

ADIM 01

According to the design drawing, place the wires on one side of the front of the metal base plate and fill the enamel glaze on the other side. For the first layer of glaze on the front, you can either fill different colors of enamel glaze directly according to the design, or choose to fill with transparent enamel glaze, i.e., the fundamental base glaze. Different fundamental base glaze should be used for different metal bases—for example, use a transparent base glaze for copper on copper, a transparent base glaze for gold on gold, and so on. Various brands of glaze have three types of basic transparent base glaze suitable for gold, silver, and copper. Figure 5–28 shows French-produced No. 1 and No. 3 fundamental base glaze, suitable for gold and silver, respectively. To leave enough room for the subsequent layers of enamel glaze, this layer should not be applied too thickly; it only needs to cover the base so that the metal wires are fixed. But it should also not be too thin—if the base glaze is applied too thinly, the unfixed silver wires may fall off when the piece is turned over to fire the back glaze. Figure 5–29 shows the situation when filling the first layer of enamel glaze. In this example, the first layer did not use a transparent base glaze but filled the various colors required by the design directly, which yields clearer color effects. However, note that when firing on a silver base plate, if the design will use warm-colored glaze such as red, yellow, or magenta, the areas where the first layer directly contacts the metal must be fired with transparent base glaze, because warm-colored glaze can react with the silver base during high-temperature firing and cause serious color changes. In such cases, the transparent base glaze serves not only to fix the silver wires but also as a barrier layer.

Figure 5–28 Transparent fundamental base glaze for gold and silver

Figure 5–29 Applying the first layer of glaze

ADIM 02

After drying the moisture, please place it in the kiln and fire at 850°C until the glaze is completely melted. When firing the first layer of glaze, if you find some silver wires and the silver base plate is not fully adhered, you can gently press the unadhered silver wires downward with a palette knife when the piece comes out of the kiln, so they fully adhere to the base plate. Figure 5–30 shows the silver wires fully and securely fixed to the silver base plate after firing.

ADIM 03

Apply the first layer of back glaze to the back of the piece. This layer can also be a transparent base glaze. The glaze thickness should be similar to the first layer on the front, or slightly thicker, as shown in Figure 5–31. After drying the moisture, fire in the kiln at 850°C.

STEP 04

Apply the second layer of glaze to the front. From this pass onward, different colors of glaze are applied to areas of the front according to the design; the glaze thickness is the same as in the first pass, as shown in Fig. 5-32.

Repeat the firing process accordingly, alternating one pass on the front and one on the back, until the glaze on the front, when fired, slightly exceeds the height of the silver wires, as shown in Fig. 5-33. Because cloisonné enamel works rely on a polishing process to achieve a smooth surface, the glaze on the front needs to be fired slightly above the upper edge of the silver wires so that, after polishing, a flat surface can be formed.

To achieve rich color effects, the front side of a cloisonné enamel piece often needs to be fired 4 to 5 times or even more. Unlike the front, the back glaze needs at most three layers of firing to counteract tensile stress and reduce deformation; it does not need to match the number of layers on the front exactly. The overall thickness of the back glaze can also be slightly thinner than the front, but the difference should not be too great.

Notes

(1) Because the metal base plate is formed into a convex, domed shape and the metal wires are fashioned into a pattern on a flat plane during the cloisonné process, when placing the prepared metal wires onto the domed metal base plate, you may encounter situations where the wires do not conform to the base. This must be resolved promptly; otherwise, it will cause color bleeding between different enamel glaze colors. Figure 5-34 shows a case of color leakage caused by the wire bottoms not fitting closely enough.

When the wire does not fit closely, you can, after the first layer of base glaze has been fired and taken out of the kiln, gently press the non-adhering metal wire downward from directly above the piece with a palette knife. At this time, the glaze on the surface has not yet solidified; by applying a little downward force, the originally non-adhering metal wire will be fully pressed onto the base plate. Figure 5-35 shows the situation of using a palette knife to press the wire down until it fits the base plate. Be careful not to press too hard, because the glaze is still not solidified and is in a semi-molten state; excessive force can easily cause the metal wire to tilt, shift, or even collapse.

Figure 5-34 Color leakage caused by the wire's bottom not fitting closely

Figure 5-35 Pressing the wire to fit with a palette knife

(2) The first layer of enamel glaze on the front can be filled to about half the height of the metal wires; after firing, the enamel glaze will sink somewhat, then the next layer of enamel glaze is filled to half of the remaining metal wire height… Repeat this operation until the fired enamel glaze is slightly higher than the metal wires. Typical cloisonné works are fired more than three times on the front, and the back also needs to be fired at least twice. If you increase the thickness of the enamel glaze applied each time to reduce the number of firings, although the production time is shortened, the fired color will appear dull, not sufficiently translucent, and bubbles are more likely to form. The test piece shown in Fig. 5-36 attempted to use two layers of enamel glaze for firing, and it can be observed that the color rendering of the enamel glaze is poor.

Figure 5-36 Test piece with enamel glaze filled by firing only twice

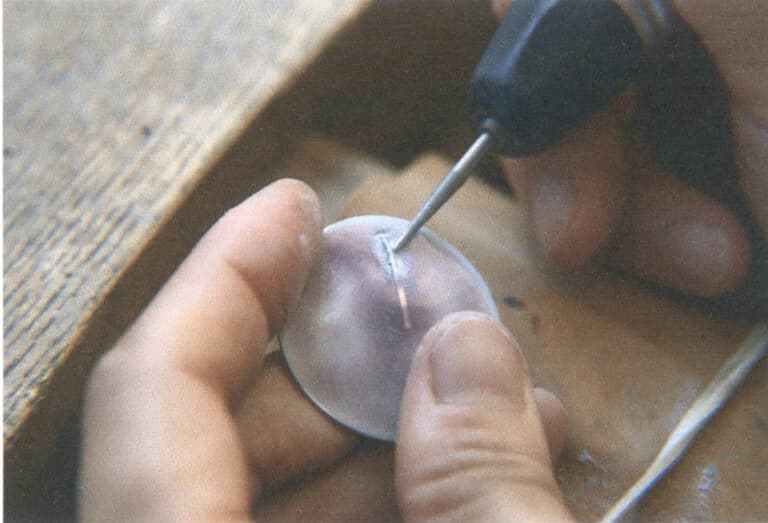

(3) If metal wires collapse during the firing process, use a hanging flex shaft grinder and a diamond grinding bur to remove the enamel glaze around the collapsed wires, take out the collapsed wires, as shown in Fig. 5-37, and then recloison and refill the enamel glaze.

Figure 5-36 Test piece with enamel glaze filled by firing only twice

Figure 5-37 Removing metal wires embedded in the glaze with a hanging flex shaft grinder and a diamond grinding bur

(4) The firing temperature for each layer of enamel glaze depends on the type of enamel and needs to be adjusted at any time. As mentioned earlier, each enamel glaze has a different melting temperature, especially the melting and firing temperatures of transparent and opaque glaze differ greatly. Hence, the temperature of the enamel kiln needs to be determined for each firing based on the enamel glaze being used.

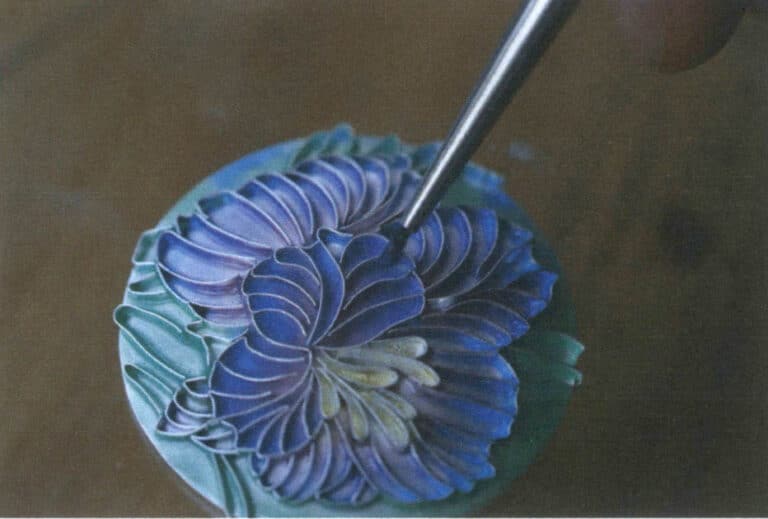

2.3 Gradient Effects of Transparent Glazes

Since cloisonné enamel is fired multiple times layer by layer, if transparent glazes are used, the transparency of the glaze and the layered firing process can be used to create color gradient effects.

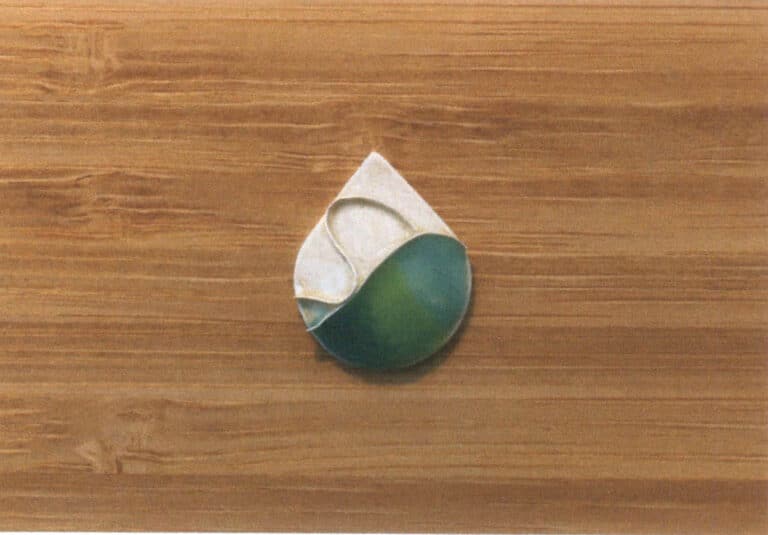

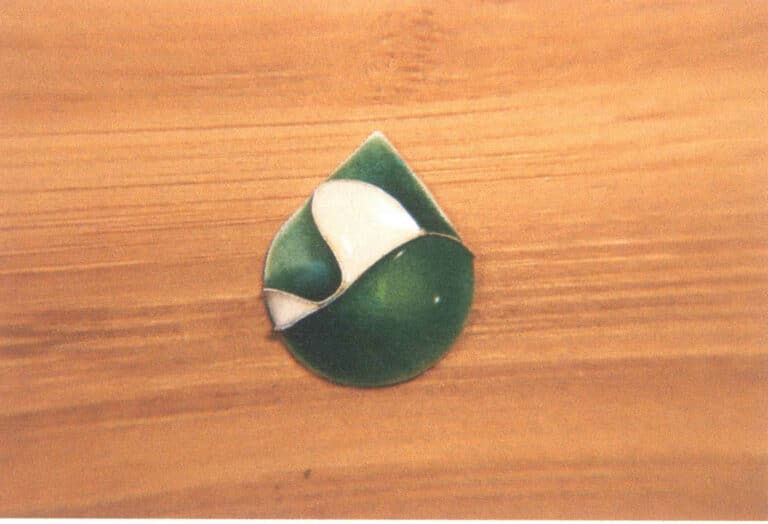

Taking a leaf shape as an example, select three transparent glazes with progressively different color values, such as light green, medium green, and dark green (here the French glazes No. 256, 189, and 49 are chosen), as shown in Fig. 5-38.

The specific operating steps are as follows.

ADIM 01

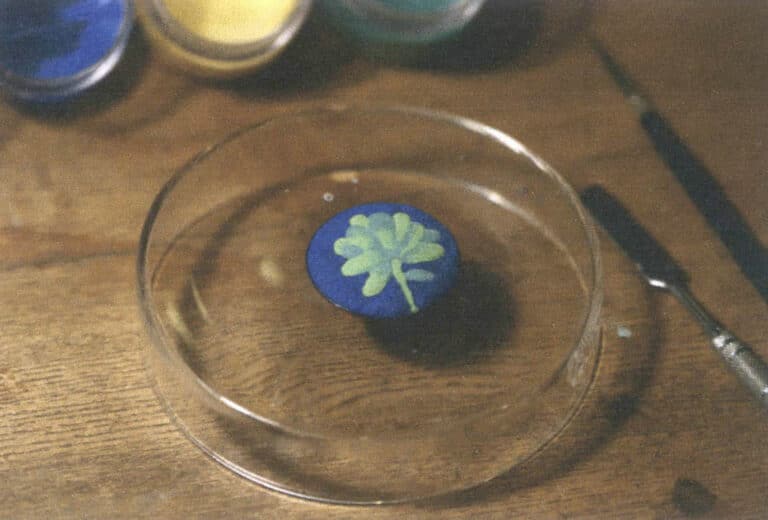

Shape the design with silver wire, placing the wire while filling in the glaze. Fire the first layer of base glaze and the first layer of back glaze; after firing, the silver wire will have been fixed to the base plate by the first base glaze, as shown in Fig. 5-39.

ADIM 02

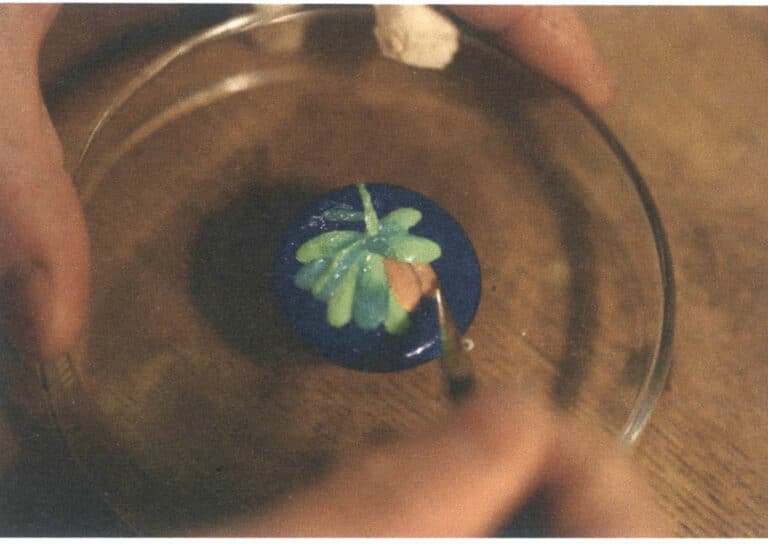

Apply glaze No. 256 to the brightest parts of the blade as designed, glaze No. 189 to the middle transition areas, and glaze No. 49 to the deepest parts. At the positions where the two colors meet, repeatedly move a small brush used for applying glaze back and forth so that the two colors blend together and transition smoothly, as shown in Fig. 5-40. Set the kiln temperature to 850°C for firing; after cooling, you can see that the boundaries among the three colors have become more distinct than before firing, as shown in Fig. 5-41.

Figure 5-40 Glaze showing smooth color transition

Figure 5-41 Color boundaries become distinct after firing

ADIM 03

On the fired glaze, create the gradient effect again using the three colors by repeating the previous step, moving the junctions of the two colors toward the lighter side, as shown in Fig. 5-42, then fire in the kiln at 850°C.

Repeat the same operation until the glaze fills to a level slightly higher than this silver wire; using this method produces a very even and natural color gradation. Figure 5-43 shows the effect of a uniform green gradation after firing.

Using the transparency of transparent glazes, other color variations can also be created. For example, a layered staining like gongbi painting, that is, firing a layer of another transparent color over one transparent color, or creating a gradation first and then firing another transparent color over it. By these methods, effects similar to the bleeding of watercolor painting can be produced. The background behind the swallowtail flower shown in Fig. 5-44 was created using this method.

By taking advantage of the transparency of transparent glazes, the colors in the painting can also be adjusted. For example, a transparent light blue can be applied over an already-fired green and fired again, producing a bluish green; or a transparent pink can be applied over blue, yielding a purplish blue.

Figure 5-43 The effect of an even color gradation after firing

Figure 5-44 The background uses a soft wash effect

2.4 Polishing

After firing, the surface of cloisonné enamel looks very flat, but it is not truly planar. Not only are the heights of the enamel areas and the metal wires not the same, but the enamel also inevitably has slight undulations. In this situation, the light reflected from the work’s surface is scattered, which affects the presentation of patterns and colors. Figure 5–45 shows an unfined cloisonné piece after firing, where the front glaze is level with or slightly higher than the silver wires. As can be seen, although the surface appears generally smooth, it is not a truly uniform curved plane. It is necessary to perform the grinding step to make the enamel and the metal wires exactly the same height so the piece presents a truly flat surface.

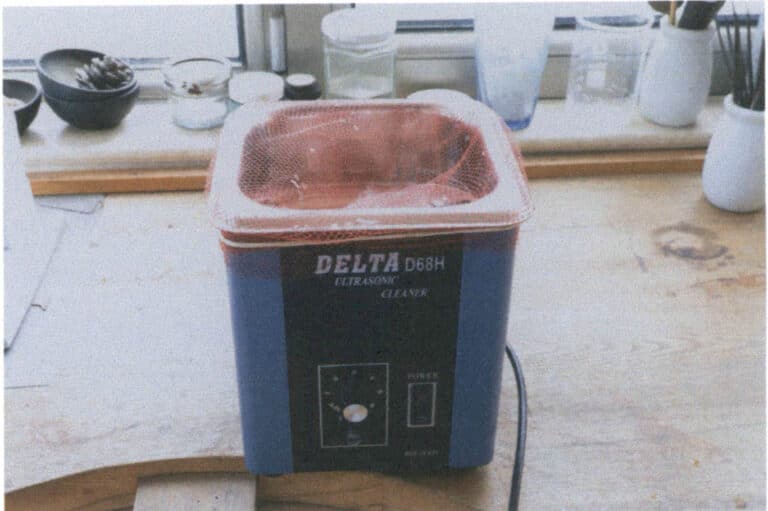

The polishing method described below requires water, a 320-grit polishing oil stone, 600-grit sandpaper, and an ultrasonic cleaner. Figure 5–46 shows a small ultrasonic cleaner; an ultrasonic cleaner of this size is more suitable for creating jewelry enamel pieces.

Figure 5–45 Unpolished piece after firing

Figure 5–46 Ultrasonic cleaner

The polishing steps for cloisonné enamel are as follows.

ADIM 01

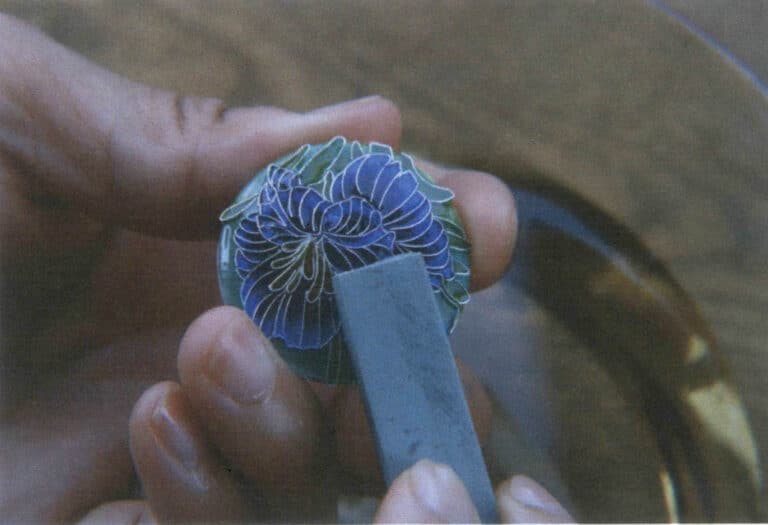

Place a 320-grit polishing oil stone and the enamel piece together in water to soak, then gently press the polishing oil stone against the surface of the piece and polish in a circular motion, as shown in Figure 5-47. During polishing, continually dip in water; the polishing oil stone and the piece being polished must remain wet at all times to avoid scratches. Do not apply too much force when using the polishing oil stone, especially around edges where the silver wire is exposed—be careful, because the enamel layer is usually thinner where the silver wire is exposed. The unprotected silver wire has no strength. If the polishing oil stone drags the wire, it can cause cracking or flaking of the surrounding enamel.

STEP 02

Wipe the surface of the enamel piece dry with a paper towel and inspect the polishing condition by looking at reflections. Areas that appear dull or matte are where the oil stone has polished; areas that still appear glossy and glass-like are places not yet polished, as shown in Figure 5-48.

Figure 5-47 Polishing in circles with an polishing oil stone

Figure 5-48 Partial area sanded to a matte finish

ADIM 03

Continue sanding the areas that were not sanded previously until all parts present a matte appearance, as shown in Figure 5-49.

STEP 04

Use 600-grit sandpaper dipped in water to sand the surface of the piece until the silver wires present a shiny effect, as shown in Figure 5-50. When sanding, wet the sandpaper with water and press it firmly against the surface, sanding until the silver wires and the glaze on the surface become very smooth and even. This step requires applying some pressure because the abrasive grains of the sandpaper are quite fine and will not be effective without force.

Figure 5-49 Surface of the piece fully matte

Figure 5-50 Fine sanding with sandpaper

STEP 05

Place the piece in an ultrasonic cleaner and clean for 15 minutes, as shown in Figure 5-51. This step serves to remove oil stone particles and sandpaper debris left from polishing, so that these contaminants are not fused into the enamel layer during the subsequent firing process.

STEP 06

Put the piece into the kiln for the final time and fire it briefly at a high temperature above 850 °C, so the piece once again presents a smooth glass-like surface; this process is called “glaze firing.” The principle of the glaze firing is a high kiln temperature with a relatively short time in the kiln. After this high-temperature, short-duration firing, the enamel glazes will be thoroughly and completely fired, revealing each glaze in its most perfect state. With this, a cloisonné enamel piece is finished; Figure 5-52 shows the final work after glaze firing.

Figure 5-51Cleaning with an ultrasonic cleaner

Figure 5-52 The finished work

Notes

(1) While using the polishing oil stone for sanding, always observe the piece to ensure the polishing oil stone evenly sands all areas of the enamel surface, avoiding excessive sanding of any single spot. This is especially important when the work’s base is arched; the highest point of the arch is easily over-sanded, causing the glaze there to become thinner than at other locations. Another reason to watch continuously is that once all areas have been sanded to a matte finish, you should stop immediately to minimize glaze wear and prevent colors from becoming insufficiently saturated.

(2) Be sure to keep both the enamel piece and the polishing oil stone consistently wet; adequate moisture prevents the polishing oil stone from leaving scratches and particulate debris on the enamel surface. Some enamellers even perform this step under running water from a tap.

(3) When bubbles are found in the enamel layer and need to be removed, first break the glaze on the surface of the bubble with the tip of a diamond grinding bur, as shown in Figure 5-53, then use the diamond grinding bur to enlarge the cavity into a trumpet-shaped pit that is smaller at the bottom and larger at the top, as shown in Figure 5-54, and fill the pit with glaze for firing. If the cavity is not first enlarged into a sloped pit, when filling with glaze, the surface tension of the water will prevent the glaze from entering the originally very small bubble cavity. After filling, this area still needs to be ground smooth again.

Figure 5-53 Opening a bubble with a diamond grinding bur

Figure 5-54 The bubble hole enlarged into a beveled pit