Looking for the Ultimate Guide to Enamel Jewelry Making? Discover Painted Enamel & Special Techniques!

Painted Enamel & Special Enamel Techniques Guide for Jewelry Making

Innledning:

Looking to master intricate enamel techniques for your jewelry designs? This guide provides a thorough walkthrough of key processes and decorative methods. First, it details the creation of painted enamel art, covering essential steps like preparing the metal base, firing the foundational glazes, and the painting process itself—including tool setup, color mixing, layering, and precise temperature control during firing. Following that, the resource explores a variety of special effects. Learn techniques such as dry sieving for smooth color gradients, using glaze outlining for fine details, marbling for organic patterns, tread drawing for fluid designs, pencil sketching for graphic effects, and applying materials like glaze granules, threads, gold leaf, and silver leaf for rich texture and luxury finishes. It’s the perfect resource for designers and brands aiming to create unique, high-quality custom pieces or expand their product lines.

Glaze granules

Innholdsfortegnelse

Section I Production of Painted Enamel

Strictly speaking, compared with the enamel techniques introduced earlier in this book, such as cloisonné enamel and plique-à-jour enamel, painted enamel should be considered a different process. This is because, compared with the other enamel techniques discussed here, painted enamel uses a different base material, different glaze textures, different methods of production, and different firing temperatures. The glazes of the other enamel techniques are fired onto metal bases, whereas the painted enamel glazes are fired onto enamel base plates; the powdered pigments for painted enamel are much finer than those for ordinary enamel glazes; other enamel glazes are mixed with water for use, while painted enamel pigments are mixed with oil; and the firing temperature for painted enamel is much lower than that for other enamel techniques.

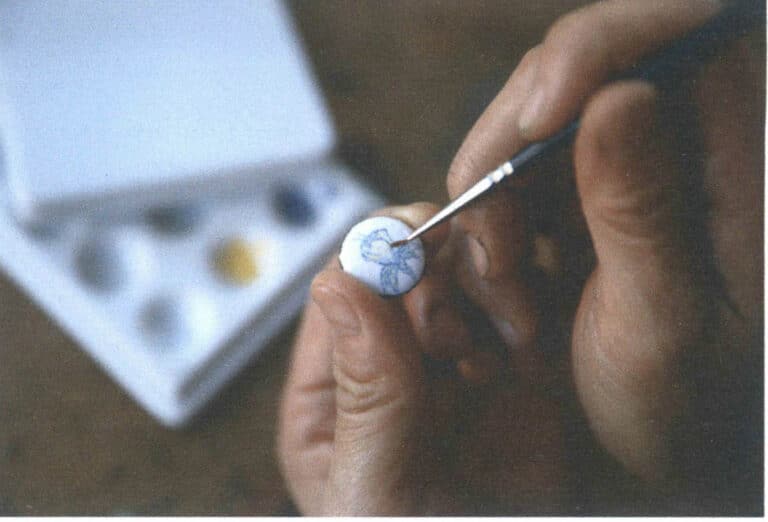

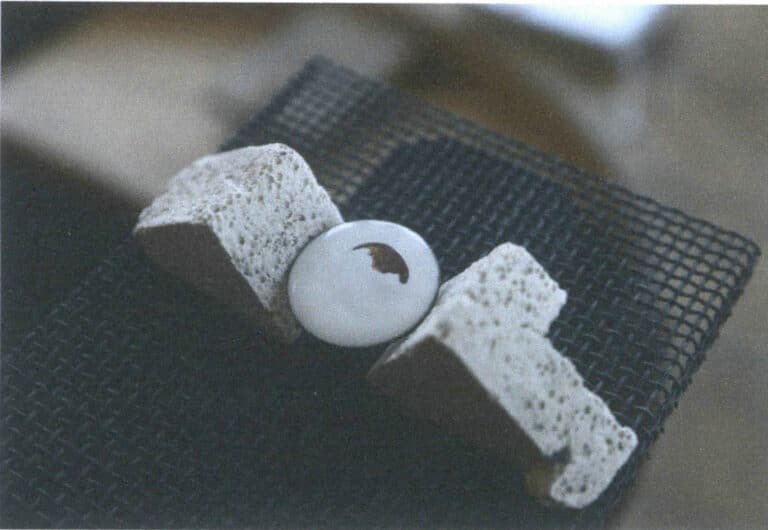

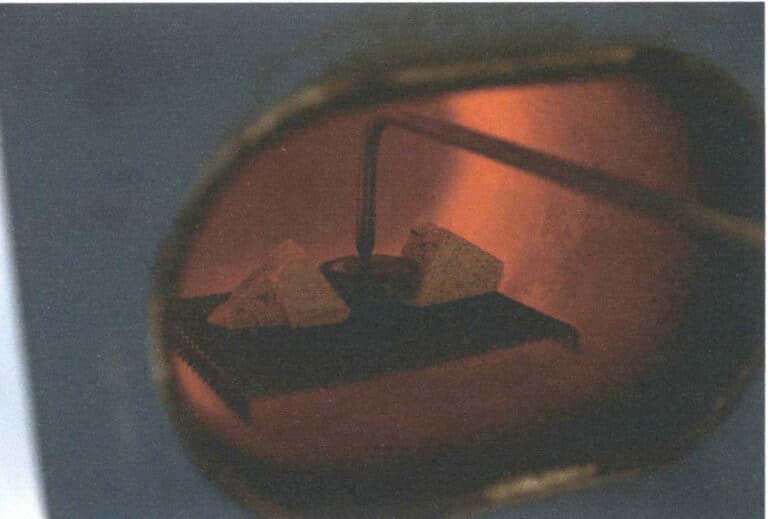

Figure 8-1 shows the situation where a porcelain-white base glaze has been fired onto a copper base, and painting is carried out on top of that porcelain-white base glaze.

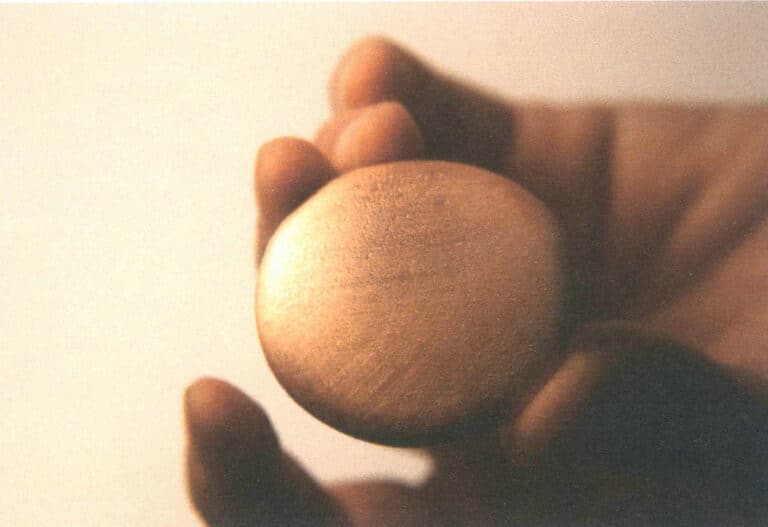

1. Preparation of the Metal Base

As mentioned earlier, painted enamel must be fired on an enamel base plate; that is, to create a painted enamel piece, you must first fire a layer of enamel onto a metal base, and only then can the painting and subsequent firings be carried out.

In general, unless there are special requirements, copper base plates are chosen for making painted enamel. The glaze used for the ground layer is usually an opaque white or light colour, and once applied, you cannot see the colour of the metal beneath, so there is no need to use gold or silver base plates.

First, cut the copper base plate to the shape and dimensions specified by the design, then, using the method described in previous articles, work the copper base into a slightly convex shape. One purpose is to increase the strength of the copper base and reduce deformation; additionally, the raised shape makes the image appear fuller.

The preparation steps for the metal base plate are as follows.

STEP 01

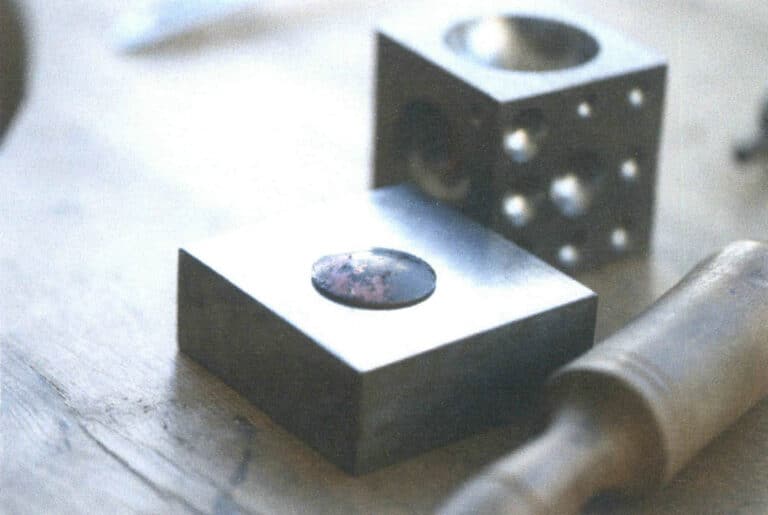

Saw a piece from a 1 mm thick copper base plate to the required shape, anneal the base plate, form it into a slightly domed shape using a semicircular concave die, and gently flatten the four edges with a wooden mallet, as shown in Fig. 8-2.

STEP 02

Soak the metal base plate with the prepared shape in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for 15~20 minutes, until the surface is clean and bright. Remove it and rinse thoroughly with clean water for later use, as shown in Figure 8-3.

Figure 8-2 Copper base plate processed into a domed shape after annealing

Figure 8-3 Rinsing a copper base plate that has been acid-treated with clean water

2. Firing the Back Glaze and Base Glaze

As with other enamelling techniques, to prevent the glaze on the front of the piece from cracking, a layer of glaze must also be fired on the back of the piece, with a thickness similar to that of the front glaze.

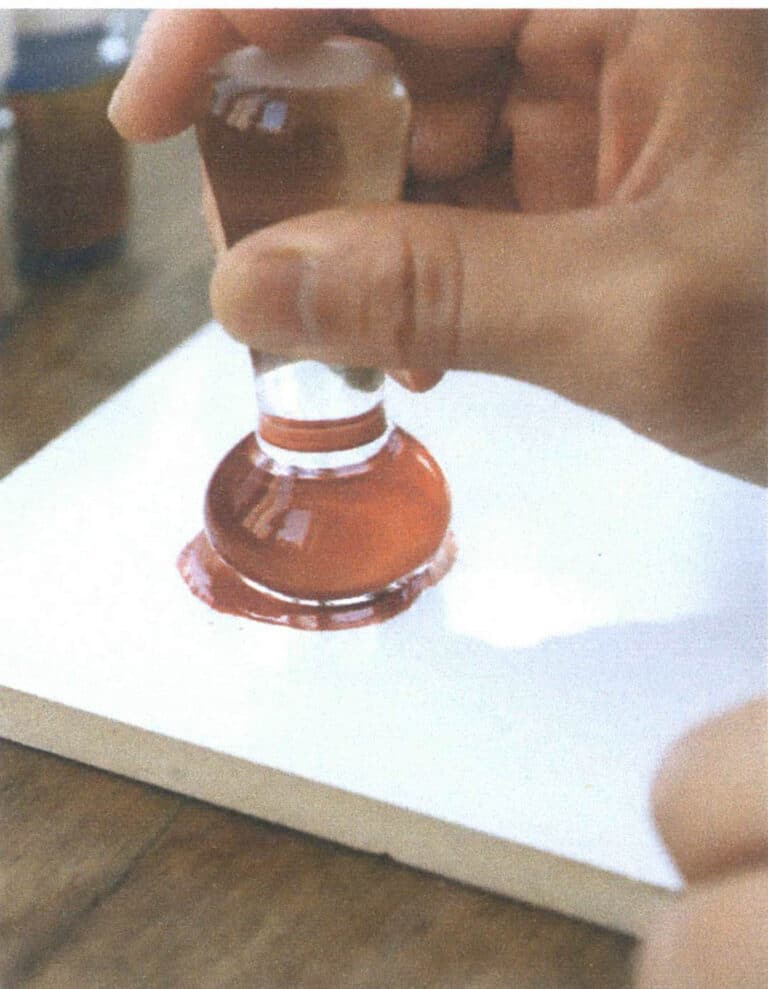

Place the thoroughly cleaned metal base plate with the recessed side facing up, and apply the glaze starting from the centre and spreading outward; see Chapter 4 for a detailed method. After the glaze has been applied completely, fire it in a kiln at 850°C. Figure 8-4 shows the base plate with the transparent back glaze fired; the back glaze used is the bright white from the Chinese cloisonné glaze series.

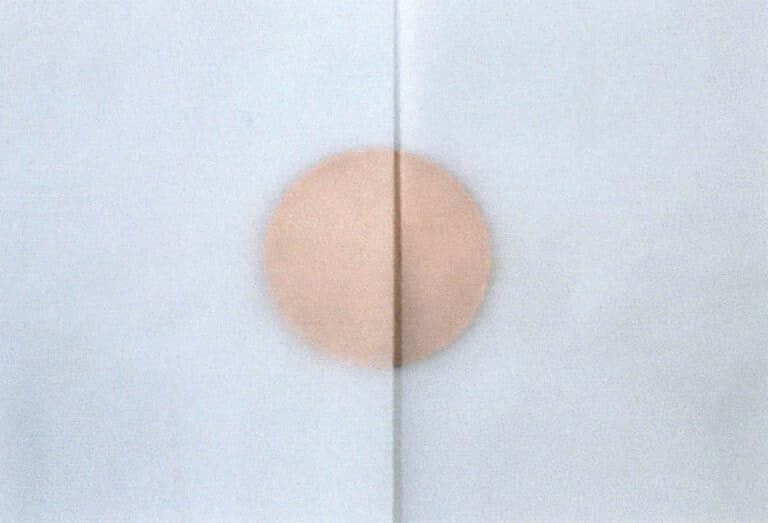

After the back glaze is fired, apply and fire the base glaze on the front side using the same method. For painted enamel, the base glaze is typically made of white opaque glaze, such as the “Porcelain White” or “Matte White” from cloisonné enamels produced in China. Alternatively, any opaque light-colored glaze can be used, such as beige or cream-colored glazes. Figure 8-5 shows a round copper plate fired with a white base glaze, using “Porcelain White” from Chinese cloisonné enamels. The copper plate measures 4 cm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness.

Figure 8-4 Base plate with back glaze fired

Figure 8-5 Base plate with porcelain white glaze fired

The front base glaze can be applied in the same way as the back glaze, but because it serves as a “canvas,” it must be very smooth, even, and possess a certain thickness so that the glaze colour can completely cover the colour of the copper base. When applying the base glaze, you can also choose the dry-sifting method; its advantage is a smooth glaze surface, while its drawback is insufficient glaze thickness, often requiring the process to be repeated two to three times for the glaze to reach the needed thickness. For specific operational details of the dry-sifting method.

After the back glaze and base glaze have been laid on the metal base, the production of painted enamel can begin.

3. Production of Painted Enamel

The production of painted enamel differs greatly from other enamel techniques: the tools used are different, the methods for preparing the glaze are different, and the firing temperatures are different.

In the process of making painted enamel, preparing the glaze is a key step. The success of an painted enamel depends primarily on the artist’s painting skill, and secondly on whether the glaze has been properly prepared.

3.1 Tools for Painted Enamel

The tools used for painted enamel are completely different from those used in other enamelling crafts; by comparison, painted enamel is much closer to painting. Apart from the firing process, creating a painted enamel piece is entirely the process of producing a painting.

The process of making painted enamel can be divided into two stages: the painting stage and the firing stage. The tools required for the firing stage are the same as those for other enamelling crafts and will not be repeated here. The tools needed for the painting stage can also be divided into two parts: tools for preparing the glaze and painting tools.

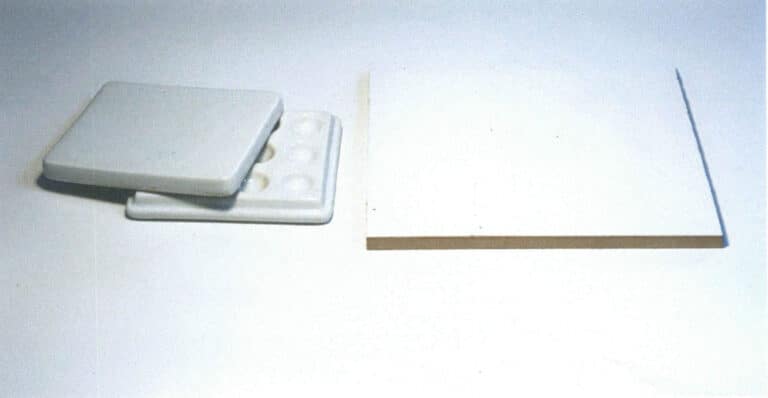

First, introduce the tools needed for preparing enamel paints. The powdered glaze for painting is extremely fine and cannot be ground and washed with water like other enamel glaze powders; it requires special tools and techniques to fully blend the painted enamel glaze powder with an oil medium so that the powder contains an appropriate amount of oil and can be applied or blended with a brush like ordinary paint during the painting process. Figure 8-6 shows the tools and materials for preparing the glaze, including a palette, glass grinding pestle, palette knife, essential plant oils, and painted enamel neutral oil. The following gives a detailed introduction to the use of these tools.

(2) The grinding pestle is made of glass or crystal glass and is used to grind glazes, as shown in Figure 8-8. The upper half of the pestle is a straight handle, and the lower half is a flattened, rounded grinding head with a very flat surface finished to a matte texture at the bottom, designed to enable better grinding. The purpose of the pestle is to thoroughly and evenly mix glaze powder with a medium (essential oil, neutral oil) by crushing and grinding. Grinding pestles are often used to grind pigment powders for watercolour, oil painting, tempera, and lacquer painting, and can be found in art supply stores.

(3) A palette knife is used to mix glaze and oil, as shown in Figure 8-9. A palette knife can also be used to gather dispersed glaze together or to transfer prepared glaze from the palette to a mixing box. The palette knife shown in Figure 8-9 is an ordinary palette knife available at art supply stores; it is best to choose higher-quality ones, because high-quality palette knives have very smooth surfaces and edges and are more convenient to use. You can prepare two or three palette knives of different sizes and select the appropriate size according to the amount of glaze prepared each time.

Figure 8-8 Glass grinding pestle

Figure 8-9 Small palette knife

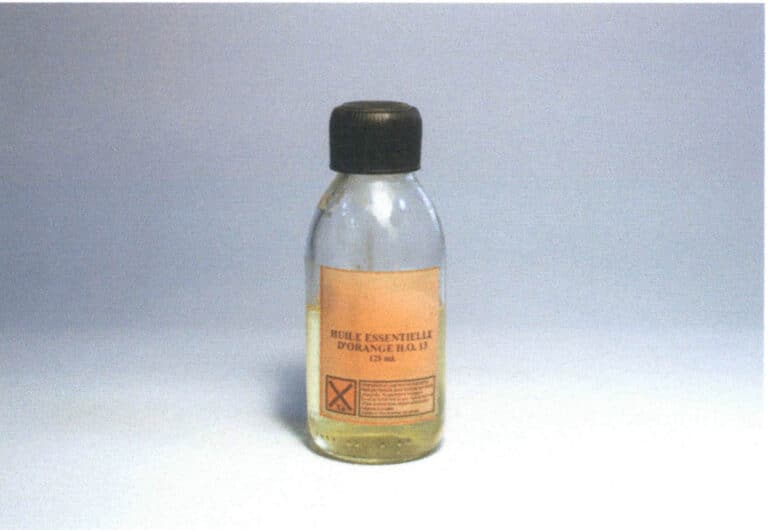

(4) Two kinds of oils are needed when preparing the painted enamel glaze: plant essential oil and a neutralising oil specifically for painted enamel. Add the plant essential oil first when mixing. The plant essential oil used for painted enamel must be a high-purity natural plant essential oil; it can be any type, such as orange oil, lavender oil, rose oil, etc. The example in this book uses the orange essential oil shown in Figure 8–10.

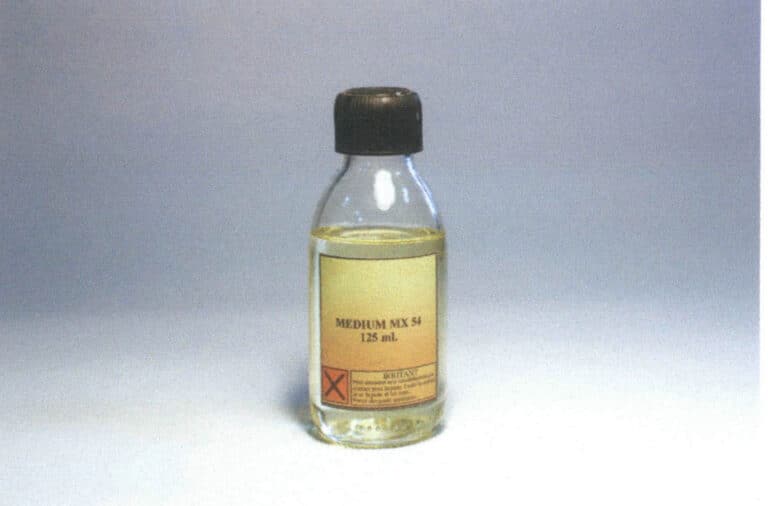

(5) The neutralising oil mentioned in this book is a neutralising oil specifically for painted enamel, used to increase the fluidity of the enamel painting glaze; it is generally available at speciality enamel glaze stores. The neutralising oil for enamel painting comes in three grades: low, medium, and high, with fluidity increasing from low to high, respectively suitable for painting colours, outlining, and drawing fine lines. Figure 8–11 shows a bottle of medium-grade neutralising oil, meaning the glaze mixed with it has moderate fluidity.

Figure 8-10 Orange essential oil

Figure 8-11 Neutral oil

(1) Painted enamel requires very fine brushes. Fig. 8–13 shows a Korean-made watercolour brush labelled five zeros. Because painted enamel typically involves very small surfaces and many details, a very fine, high-quality brush is an essential tool. You can prepare several brushes of different sizes and choose the brush size according to the intended use.

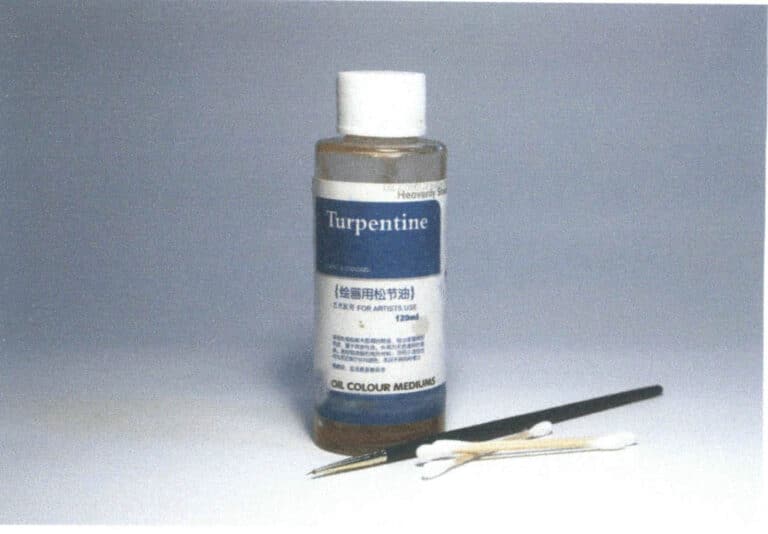

(2) The cotton swabs used here are ordinary medical or cosmetic cotton swabs, used to dip in turpentine and to wipe off mistakes or remove excess glaze, as shown in Fig. 8–14.

Figure 8–13 Ultra-fine watercolour brush

Figure 8–14 Medical cotton swab

3.2 Preparation of Painted Enamel Glaze

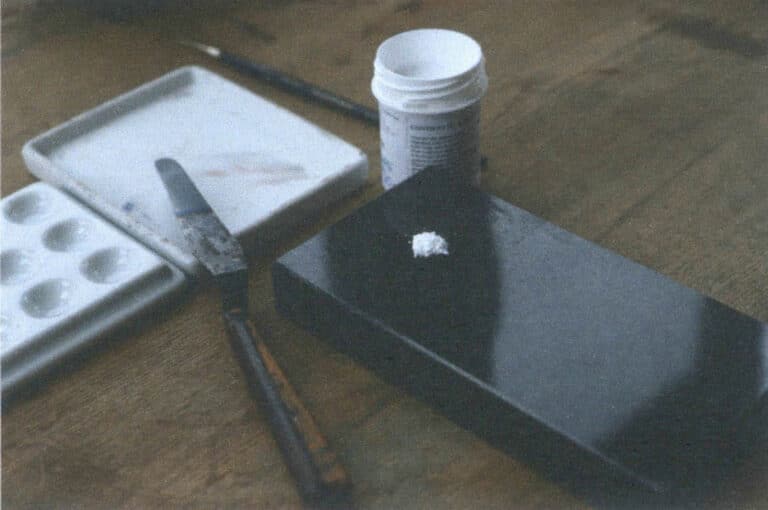

STEP 01

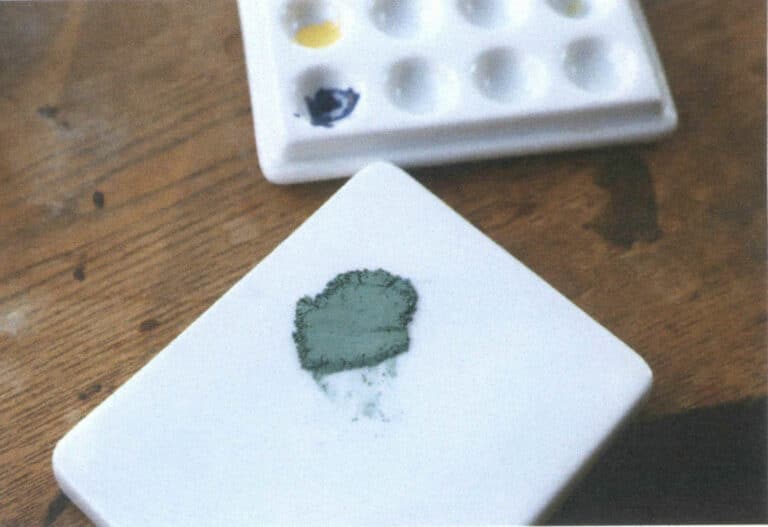

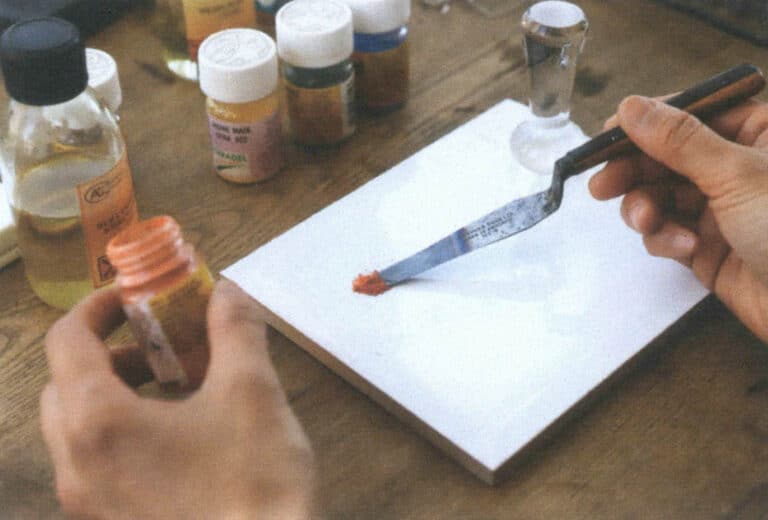

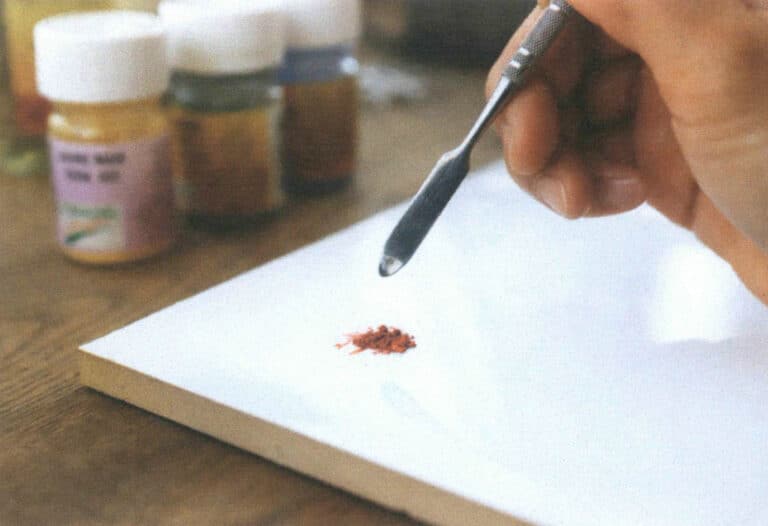

Scoop out a small amount of painted enamel glaze powder and place it on the palette, as shown in Fig. 8–17. Because the painted enamel glaze powder is very fine, be very careful when taking it—do not spill it, and do not take too much at once. You can use the tip of a palette knife or the flat end of a wax-carving tool to remove the powder from the jar. Painted enamel glaze is relatively durable, and once mixed, it cannot be stored for later use, so do not mix more than you need at one time to avoid waste.

STEP 02

Drop an appropriate amount of vegetable essential oil into the glaze, as shown in Fig. 8–18, and mix the powder and oil evenly with a palette knife. When adding the oil, wait for each drop to penetrate the powder before adding more; otherwise, it is easy to add too much. Although excess vegetable oil can be allowed to evaporate into the air, this takes a long time and makes it difficult to control the drying and moisture level.

Figure 8-17 Scooping out a small amount of painted enamel glaze

Figure 8-18 Adding an appropriate amount of plant essential oil dropwise

STEP 03

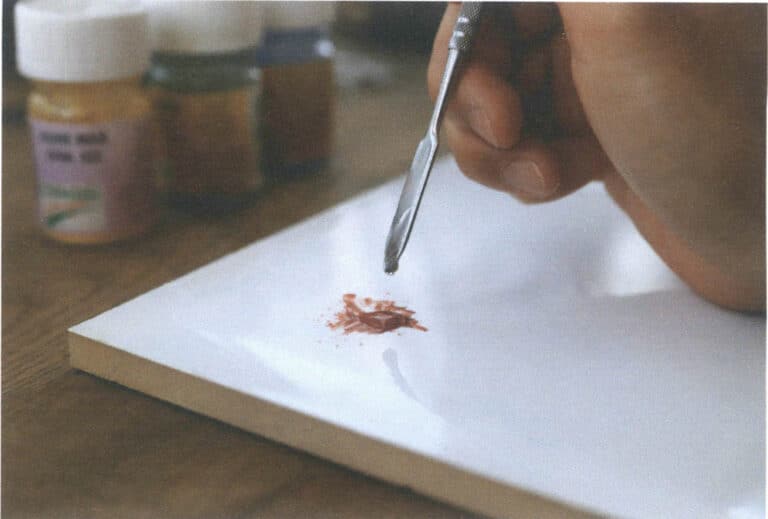

Add one drop of painted enamel neutral oil; as shown in Figure 8-19, after adding the neutral oil, the glaze becomes smoother. For the amount of glaze powder shown in the figure, 3~4 drops of plant essential oil may be added as appropriate, but only a tiny drop of neutral oil should be used; otherwise, excess can cause problems during firing. During the addition of neutral oil, it can be observed that even an extremely small amount added to the glaze will immediately dilute it and increase its fluidity.

STEP 04

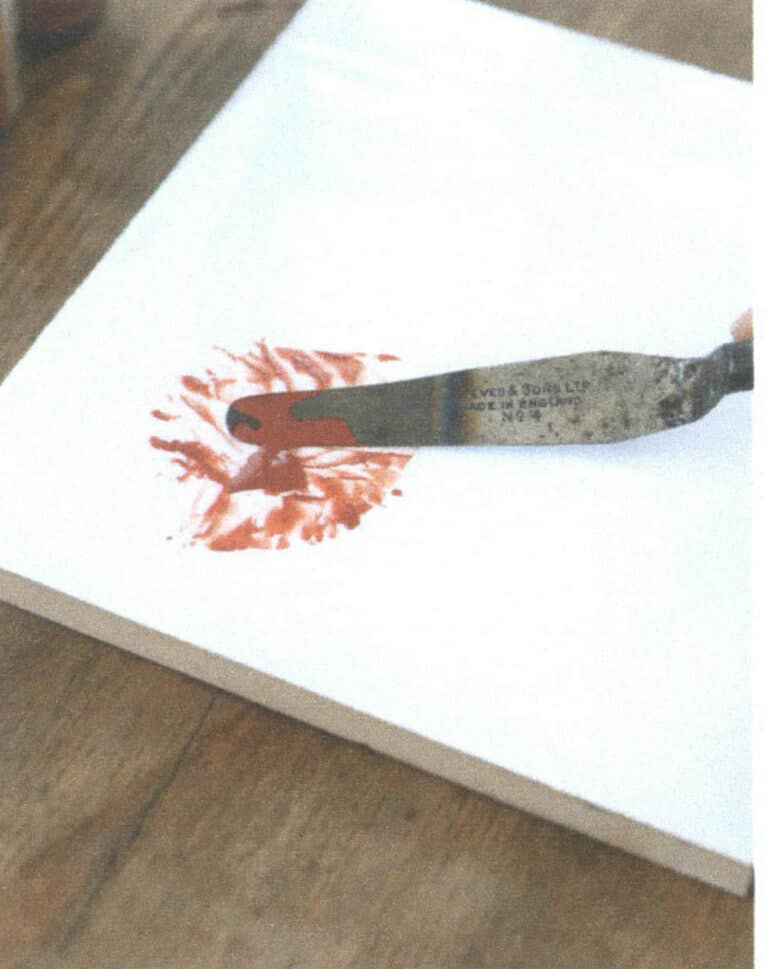

Use a palette knife to thoroughly mix the enamel glaze, essential oil, and neutral oil, as shown in Figure 8-20. Then, place the flat surface of the glass pestle against the flat surface of the ceramic tile and slowly and evenly grind in small circles, as shown in Figure 8-21. The purpose of this step is to crush any lumps in the enamel glaze and ensure it is fully blended with the two oils. During this process, the glaze must be ground sufficiently until it is completely free of any granular texture.

Figure 8-20 Mixing glaze and oil with a palette knife

Figure 8-21 Grinding glaze with a glass pestle

STEP 05

After thorough grinding, use a palette knife to gather the mixed glaze together, as shown in Fig. 8-22.

STEP 06

Transfer each of the prepared colored glazes one by one into small porcelain dishes or a palette box for later use, as shown in Fig. 8-23.

STEP 07

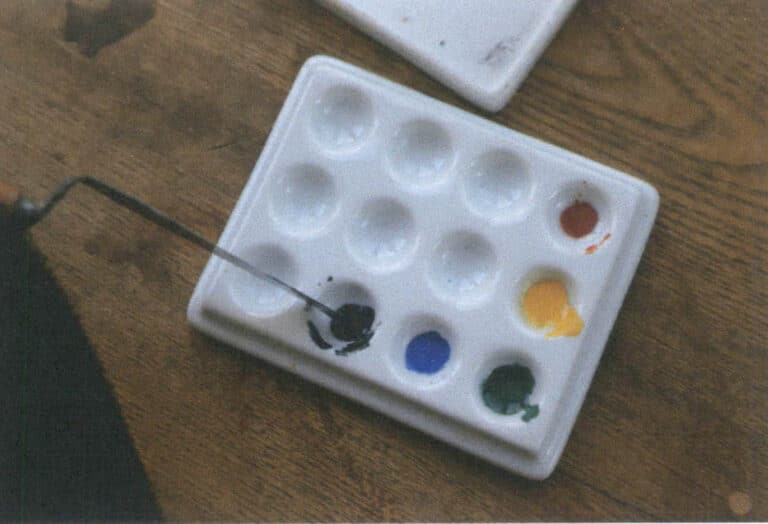

In Figure 8-24, you can see that the palette box contains several prepared painted enamel glazes, so painting can begin.

Figure 8-23 Using a palette knife to transfer the mixed glazes into a palette box

Figure 8-24 Preparation completed

Notes

(1) When preparing the glaze, you can add a bit more essential oil from plants; this makes it easier to work with. If there is too little essential oil, it is hard to mix the powder and oil. If, after mixing, you feel you have added too much essential oil, you can let it sit for a while to allow some of it to evaporate.

(2) Do not add too much neutral oil; otherwise, problems are likely to occur during firing. The oil needs to be removed during firing; essential oils evaporate easily due to their volatility, but neutral oil will remain in the glaze, so do not add too much at the start.

(3) Painted enamel glazes are like painting pigments; different colored glazes can be mixed to produce new colours. Therefore, as long as you have red, yellow, and blue, you can mix the colours you need. This means that when preparing glazes each time, you don’t need to prepare too many different colours, since many colours can be mixed.

3.3 Painted Enamel: Painting and Firing

Painted enamels are usually not completed in a single firing. The more realistic the style and the more complex the colours, the more firings are required; sometimes it may even need to be fired repeatedly, more than ten times. However, care must be taken because if fired too many times, the enamel layer used as the base colour may be damaged. For this reason, if the design is complex and requires multiple firings, it is best to choose a more firing-resistant glaze for the base layer.

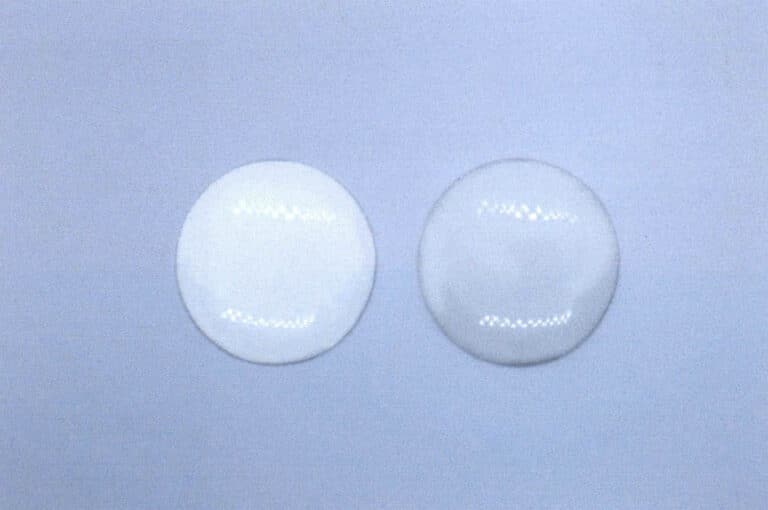

In the examples in this book, we use the porcelain white from domestically produced cloisonné glazes. The porcelain white glaze fires to a very bright white and has strong covering power. One can also choose the niè white from Chinese cloisonné glazes, which, after firing, presents a slightly greyish white with somewhat weak coverage; when used as an undercolor for painted enamel, it must be fired two to three times for the white to be even. Figure 8-25 shows the comparison between porcelain-white base glaze and niè-white base glaze: the left is porcelain-white, the slightly greyish one on the right is niè-white.

Figure 8-26 Glaze not fully matured

Figure 8-27 Checking whether the piece is properly fired by observing reflections

The specific steps for painted enamel production are as follows.

STEP 01

Clean the fired back glaze and porcelain-white ground glaze metal base plate thoroughly and dry off the moisture, as shown in Fig. 8–28. If the porcelain-white ground glaze has just been fired and the surface has not been touched, you can paint the painted enamel directly onto the ground glaze. If fingers have touched it, it should be cleaned with waste water from glaze-cleaning materials to remove any contaminants that might affect the glaze. Generally, it is not necessary to pickle the metal base plate with fired back glaze and ground glaze when making painted enamel.

STEP 02

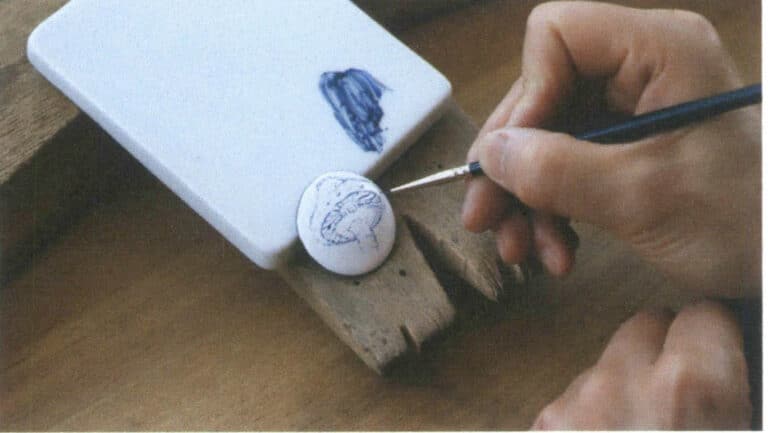

Select a dark colour from the prepared painted enamel glaze and outline the contours. Trace the line drawing onto the white ceramic base glaze according to the design, as shown in Figure 8–29.

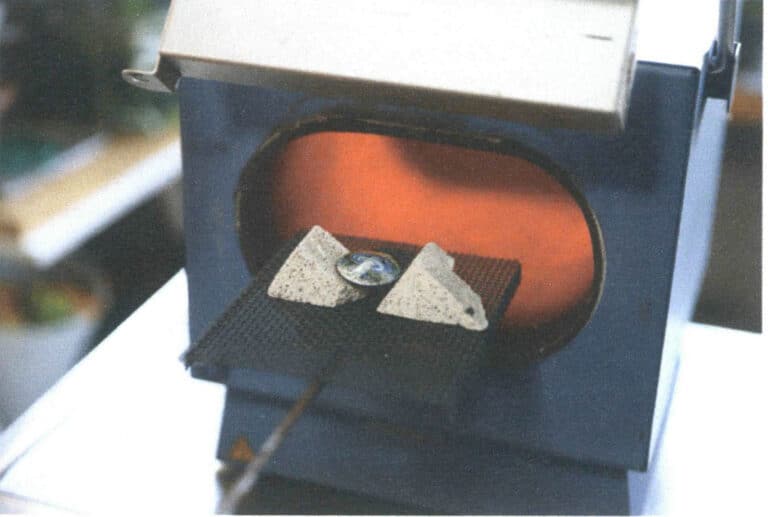

After completing the line drawing, set the kiln temperature to 780°C; first, use the kiln heat to dry the glaze and remove the oil from the glaze, then fire it in the kiln. Figure 8–30 shows the first firing process.

Figure 8-29 Outlining the line drawing

Figure 8-30 Drying the piece in the kiln

STEP 03

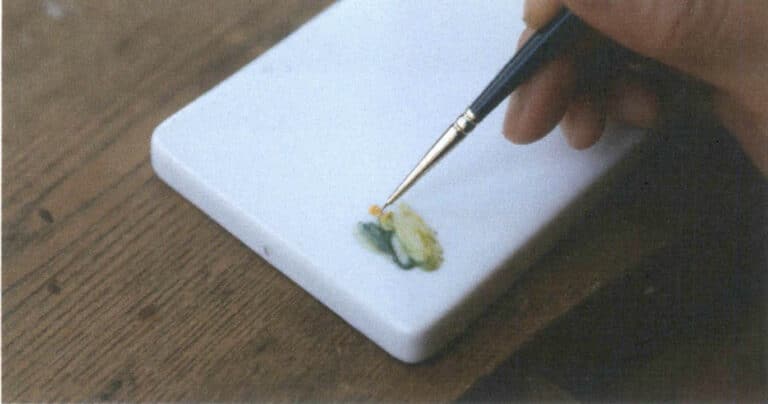

Use turpentine as a thinner to mix colours. As mentioned earlier, painted enamel glazes can be mixed like painting pigments to create new colours—for example, red plus yellow makes orange, yellow plus blue makes green… A few basic colours can be mixed to produce a fairly rich palette; Figure 8–31 shows the process of mixing colours using different hues.

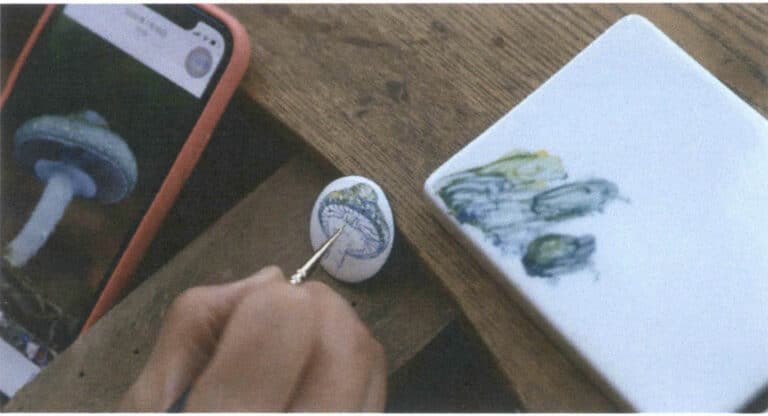

First, paint and fire the dark outline, then apply the first layer of colour. Figure 8-32 shows the work while the first layer of colour is being applied. After the entire surface has been thinly covered with colour, put it back in the kiln and fire it at the same temperature.

Figure 8-31 Colour mixing with different colours

Figure 8-32 First layer of colouring

STEP 04

After firing, apply the second layer of colour. Each pass continues on top of the previous one, gradually building up the colour layers and image details. Figure 8-33 shows the work after the second layer of colour has been completed.

STEP 05

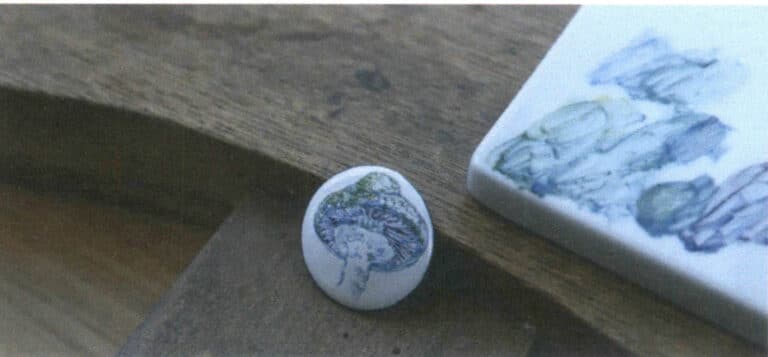

Painted enamel glazes are extremely fine powders; after a thin application and firing, the resulting colour has almost no covering power, so darker colours or more complex images require repeated colour applications and firings. If the colour is applied too thickly or too heavily at once, it is prone to insufficient firing penetration. Figure 8-34 shows the piece after the fifth layer of colour has been applied.

Figure 8-33 Second layer colouring

Figure 8-34 Fifth layer of colouring

Notes

(1) Each layer of glaze must be applied very thinly, because painted enamel glazes have almost no covering power and achieve colour saturation and depth only by repeated layering. When the glaze is applied too thickly, it often cannot be properly fired, causing the glaze colour to scorch or blur, as shown in Fig. 8–36.

(2) As with the firing process for ordinary enamel, the piece must also have the glaze baked dry before entering the kiln, but the purpose here is to dry the oil in the glaze to prevent it from affecting the glaze. Figure 8–37 shows the situation of using furnace temperature to dry the oil in the glaze before firing.

Figure 8–36 Situation of incomplete firing due to excessively thick glaze layers

Figure 8-37 Using kiln temperature to dry oils in the glaze

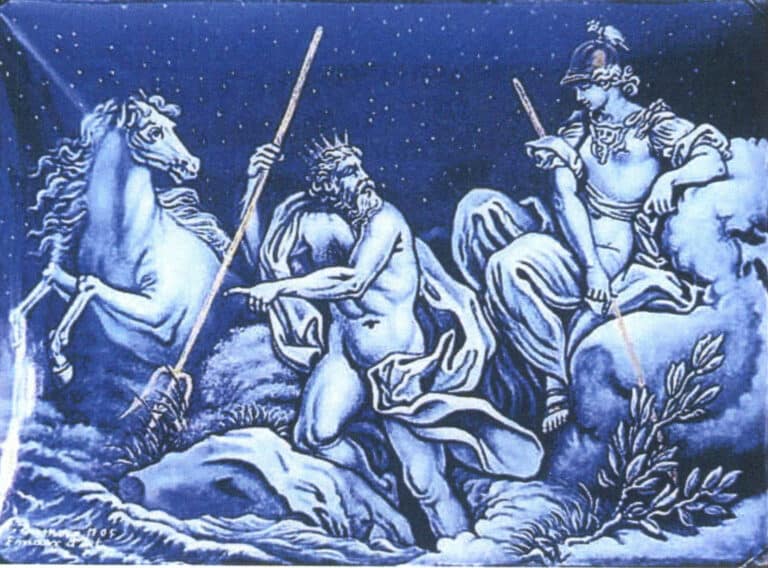

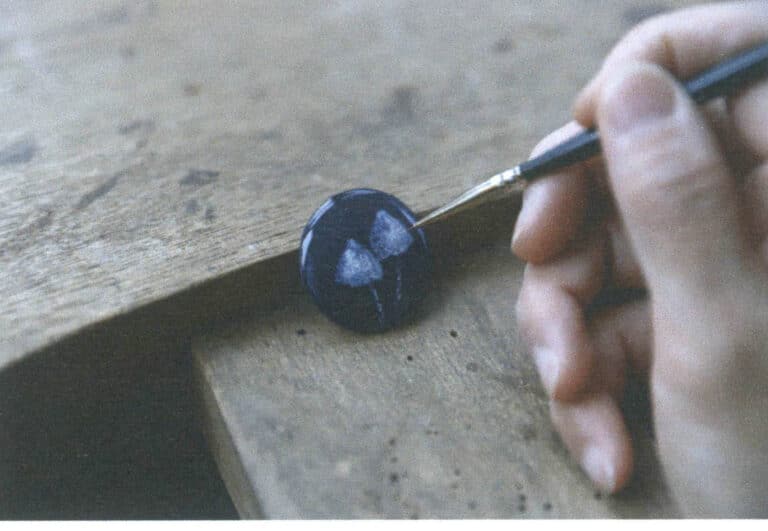

4. Drawing and Firing of Grisaille

In enamel painting, besides the commonly seen polychrome painted enamel, there is a less common technique called “grisaille.” Grisaille is an earlier form of painted enamel. Figure 8-39 shows a grisaille work created in 2010 by artist Jen Zamora, held in the Museo Archivio, an enamel museum near Milan, Italy. The painting and firing methods for grisaille are largely the same as for polychrome painted enamel; the difference is that grisaille uses a white enamel painted onto a black or deep-blue ground. By altering the consistency of the white enamel, a rich range of grey tones is produced, hence the name “grisaille.”

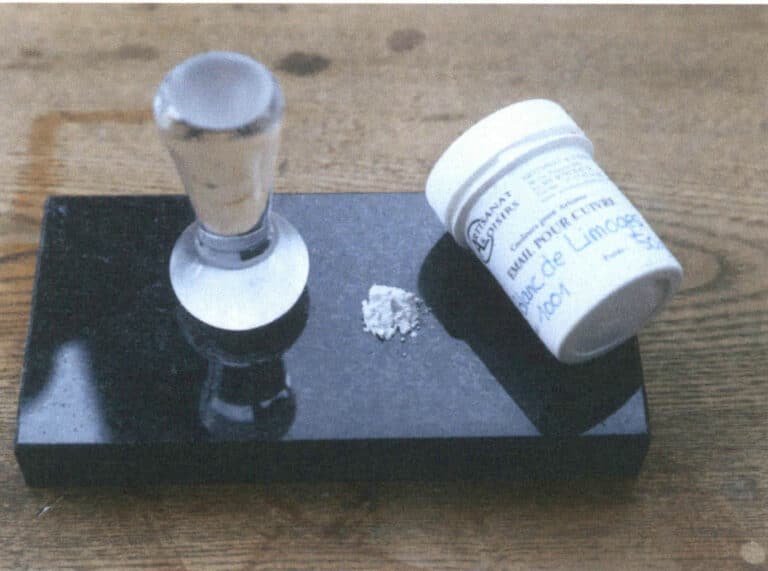

The glaze shown in Figure 8-40 is the white glaze specifically used for grisaille, Limoges white, produced in the south-central French city of Limoges. Its characteristics are strong opacity, very fine texture, and good firing durability.

Figure 8-39 Modern grisaille work

Figure 8-40 Limoges white, the white glaze for grisaille

STEP 01

Saw the copper plate to the required shape and fully anneal it. Then form it into a slight arch, pickle it in acid, remove it and rinse it with clean water for later use.

STEP 02

Apply a colourless transparent copper base glaze to the back of the copper substrate and fire it in the kiln.

STEP 03

On the front of the copper base plate with the fired back glaze, apply French No. 27 glaze and fire it in the kiln. Figure 8-42 shows the copper base pate with No. 27 glaze fired on the front.

STEP 01

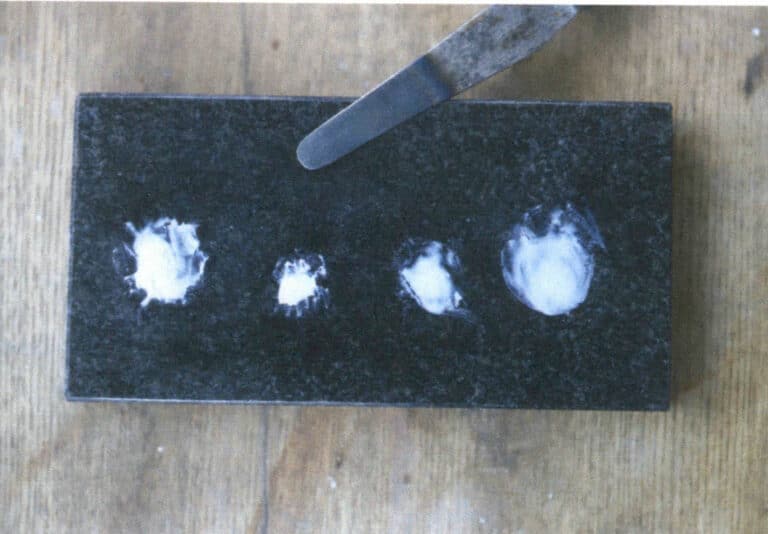

Scoop an appropriate amount of Limoges white glaze onto the palette, as shown in Fig. 8-43.

STEP 02

Following the colour painted enamel mixing method, add an appropriate amount of essential oil and neutral oil to the glaze powder, and grind and mix evenly according to the painted enamel glaze preparation method.

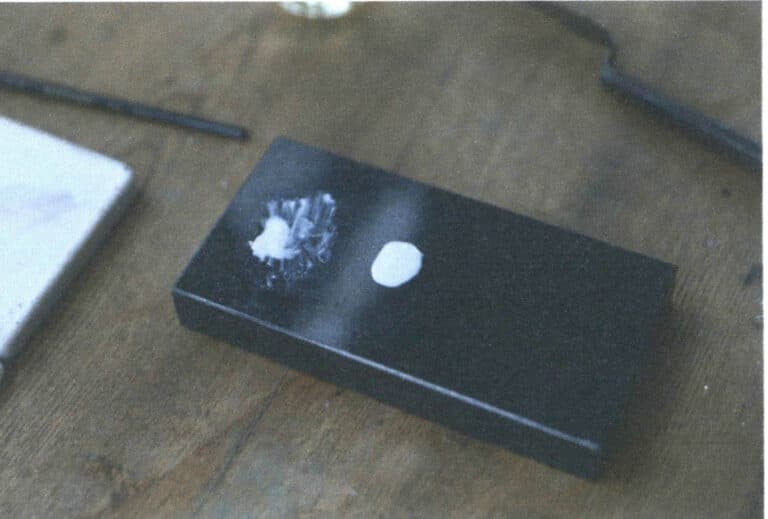

STEP 03

Set aside a small portion of the prepared Limoges white glaze and keep it aside for later use, as shown in Figure 8-44.

Figure 8-43 Scoop an appropriate amount of Limoges white glaze

Figure 8-44 Divide a portion of the prepared glaze

STEP 04

Add an appropriate amount of essential oil and one drop of neutral oil to the remaining glaze, and mix thoroughly, as shown in Figure 8-45.

STEP 05

Set aside a small portion of the prepared glaze for later use; at this point, you can observe that this portion is slightly lighter in colour than the first portion. As shown in Figure 8–46, each time oil is added to the Limoges white glaze, the white becomes a bit paler.

Figure 8-45 Adding an appropriate amount of essential oil and one drop of neutral oil

Figure 8-46 The white colour of the glaze gradually fades

Repeat the above steps until you obtain several portions of prepared white glaze ranging from dark to light, forming a gradient of tones. Place them in the paint box for later use, and you can begin painting in layers.

The painting and firing methods for the grisaille technique are basically the same as for coloured painted enamel; the difference is that grisaille is painted in white on a dark ground, building up highlights layer by layer until the light areas and specular highlights of the object or figure are completed. This is not only the opposite of the painted enamel technique but also contrary to the general painting process, so beginners often need a period of adjustment before they can handle it confidently.

Below, using a practice exercise as an example, we briefly introduce the steps for painting and firing in the grisaille technique.

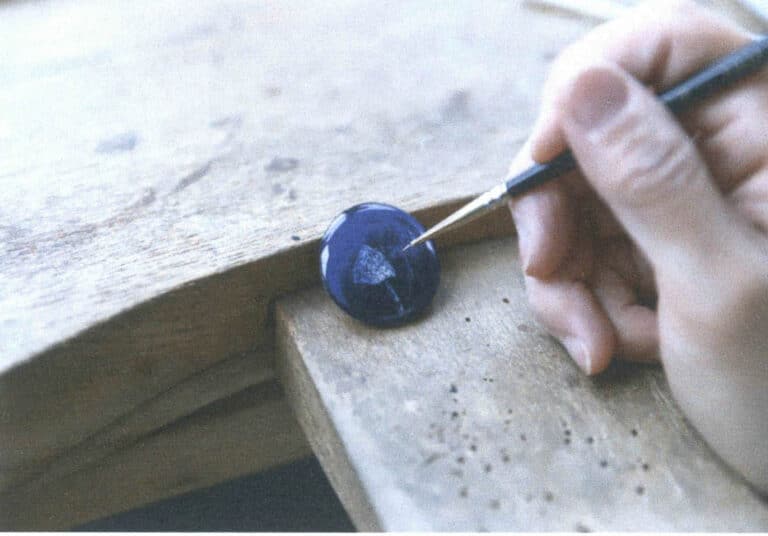

STEP 01

Select the palest white glaze to sketch the outlines, as shown in Fig. 8-47, set the kiln temperature to 700°C, and fire in the kiln.

STEP 02

From the second layer onward, choose a slightly denser white glaze to depict the tonal variations across the entire image, as shown in Fig. 8-48, and fire in the kiln.

Figure 8-47 Outlining the contours

Figure 8-48 Using a slightly denser white glaze to depict tonal layers

STEP 03

Select progressively denser white glazes layer by layer for detailed rendering; the image is gradually brightened, as shown in Figure 8-49. Grisaille, like colored painted enamel, also requires multiple applications and firings.

STEP 04

In the final pass, use the densest white glaze to outline the brightest highlights and the areas that need the most emphasis, as shown in Figure 8-50. Fire it in the kiln once more, and a grisaille painted piece is complete.

Figure 8-49 The image is gradually brightened

Figure 8-50 The completed work

Notes

(1) The firing temperature for grisaille enamel is lower than for colored painted enamel; the kiln can be set to 700°C for firing, and the condition of the glaze should be carefully observed during the firing process.

(2) Because a relatively large amount of neutral oil is added when preparing Limoges white glaze, the piece must be thoroughly dried before it goes into the kiln to allow the oil in the glaze to evaporate. Therefore, the drying time for grisaille works is longer than that required for colored painted enamel works.

Section II Some Special Techniques in Enamel Craft

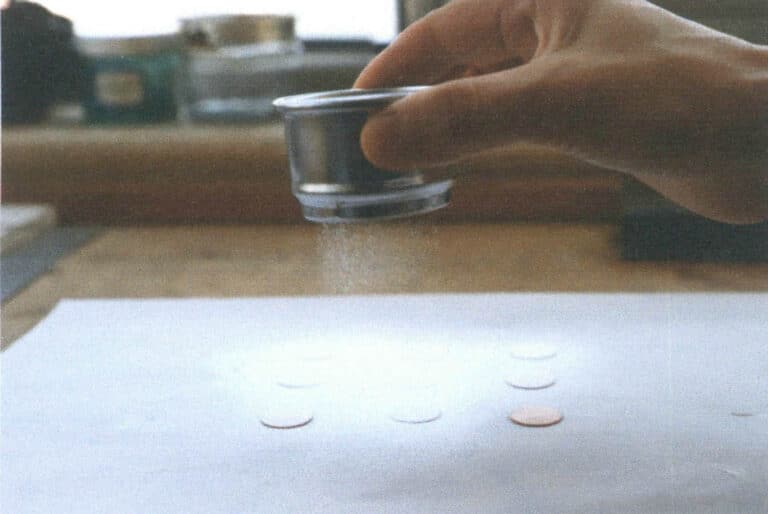

1. Dry Sieving Method

Under normal circumstances, we mix enamel glaze with water and use the adhesive force of the water to make the glaze temporarily adhere to the metal surface, then fire it. There is actually another glazing method that uses a sieve to sift dry glaze powder onto a metal base before firing; we call this method dry sieving.

The dry sieving method is suitable for spreading glaze over a relatively large area or when applying the same colour glaze to several pieces at once. Figure 9-1 shows the case of sieving a transparent base glaze onto multiple colour test plates at the same time. Compared with conventional glazing methods, dry sieving is more efficient and produces a smoother glaze surface. However, it should be noted that when using dry sieving to lay glaze, the glaze layer tends to be thin, and sometimes repeated sieving and firing are required. Figure 9-2 shows the appearance after sieving and firing one layer of pink glaze onto a copper base plate; although an opaque glaze was used, because the glaze layer applied by dry sieving is very thin, the colour of the copper base plate can still be seen through the glaze.

Figure 9-1 Sieving a base glaze onto multiple colour test plates using the dry sieving method

Figure 9-2 Copper base plate after sieving and firing one layer of pink glaze

Copywrite @ Sobling.jewelry - Tilpasset smykkeprodusent, OEM og ODM smykkefabrikk

The specific operating steps for the dry-sieving method are as follows.

STEP 01

Soak the metal base plate in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water, then set it aside.

STEP 02

Evenly spray water onto the clean, dry metal base plate with a small watering can. The amount of water is critical: if there is not enough moisture, the glaze will not adhere; if there is too much, the glaze will clump together. After spraying, you should observe a layer of fine, uniform water droplets attached to the surface of the metal base plate, as shown in Figure 9-3. Be careful that there are no large droplets of water; otherwise, when sieving and placing the glaze powder in subsequent steps, the glaze powder will concentrate in areas with more moisture, causing uneven thickness of the glaze distribution.

STEP 03

Place the water-sprayed metal base plate on the stand, with a clean sheet of white paper underneath, as shown in Figure 9-4. The stand can be made of steel or plastic; its purpose is to make it easy to place and remove the piece after the glaze has been sifted over it. The white paper is used to collect glaze powder that is sprinkled around the piece, because when sifting glaze, it is impossible to precisely control the boundary — to cover the piece completely, some glaze will inevitably fall around it.

Figure 9-3 Fine, uniform water droplets on the surface of the metal base plate

Figure 9-4 Place the metal base plate on a stand padded with white paper

STEP 04

When sifting glaze, first choose a sieve of suitable mesh size, put a small amount of dry glaze powder into the sieve, hold the sieve about 10 cm above the metal base plate, and gently tap the edge of the sieve with a metal spoon. At this point, you can observe the glaze powder falling evenly onto the metal surface, as shown in Figure 9-5.

STEP 05

Ensure the glaze powder is sprinkled evenly over the entire surface of the piece by slowly moving the position of the sieve. When the entire surface is uniformly coated with a layer of glaze powder, stop sieving and fire it in the kiln, as shown in Fig. 9-6.

Figure 9-5 Sifting glaze with a sieve

Figure 9-6 Glaze sieved to cover the metal surface

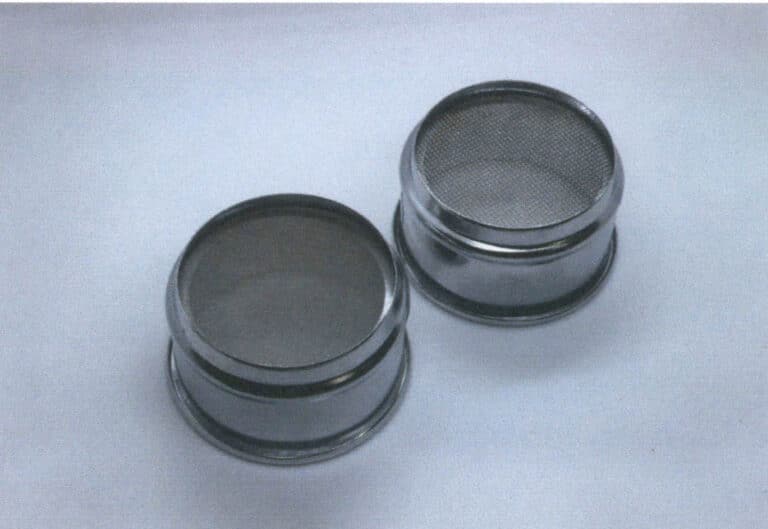

Notes

(1) When making works using the dry sieving method, a large amount of glaze powder will become airborne when the glaze is sifted, so the maker must wear a protective mask to avoid inhaling dust into the lungs and damaging their health.

(2) Screens come in different coarseness, and you can choose the mesh count according to your needs. Generally, when you need to lay glaze flat, you can choose an 80-mesh screen; if you need to create more detailed patterns, you can choose a finer screen, for example, 100 mesh. Figure 9-7 shows 30-mesh and 100-mesh stainless steel screens. Of course, if the screen is too fine, the glaze powder will not pass through smoothly, which will affect the evenness of the glaze sifting degree. In short, the coarseness of the screen should be chosen based on the needs of different works, and often relies on the maker’s experience to decide. When unsure, firing one or two test pieces first to observe the effect is the safer approach.

In addition to applying glaze in a flat, even layer, the dry-sieving method can produce many special effects. For example, by varying the density of the glaze powder, you can create colour gradients; by masking off parts, you can produce fine lines; by using masks of special shapes, you can create complex tiled patterns.

Figure 9-8 shows a gradient effect made with the dry-sieving method. On this copper-backed piece, the base glaze is a domestic cloisonné-style porcelain white that has been fired, and French No. 66 opaque blue glaze powder was sifted over it. The sifting technique is the same as for applying an even layer: move the sieve loaded with blue glaze from the right side of the piece toward the left; when you reach the middle, pause slowly and then begin moving back to the right, lingering longer at the right edge. The purpose is to make the glaze powder densest and the colour deepest at the right edge. Note that while moving the sieve left and right, the frequency of tapping the sieve rim should remain steady so the powder is sifted out at a constant speed and in a constant amount; only then can an even gradient be achieved. Experience is very important when using the dry-sieving method. The distance between the sieve and the piece, the force used to tap the sieve, the speed at which the sieve is moved, and the amount of glaze held in the sieve all affect the sifting result, and must be mastered through repeated experiments. Of course, even with rich experience and skilled technique, a certain degree of uncontrollability in this method is unavoidable; the purpose of testing and practice is to minimise that unpredictability.

When firing lines with the dry-sieving method, mask off the areas on both sides of the line according to the design, then sift other colored glaze powder over the exposed area and fire to obtain a single line. Figure 9-9 shows the situation of sifting glaze with both sides masked by stiff cardboard; besides cardboard, thin metal or plastic sheets can also be used. The same method can be used to produce curves. Lines of any thickness can be made with this approach. Note that the glaze between the two masks should not be piled too thickly; otherwise, after removing the masks, the dried glaze powder will have difficulty retaining a stable linear shape.

Figure 9-8 Gradient effect made with the dry-sieving method

Figure 9–9 The sides are blocked with cardboard before sifting and sprinkling enamel

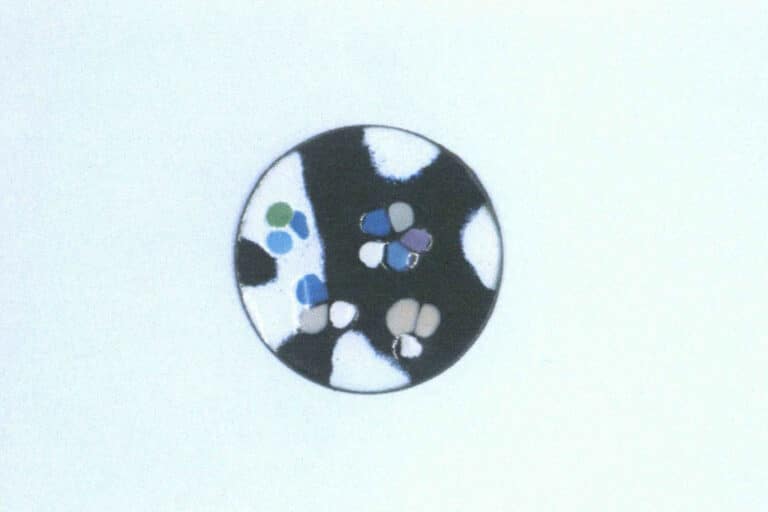

Figure 9–11 shows a tiled pattern with complex edges produced by the dry-sieving method. On a white ground fired with porcelain-white enamel, a three-petal flower-shaped metal stencil was used to mask the surface while French opaque green glaze No. 248 was sifted and fired. Then a metal stencil with a pierced pattern was applied, and French No. 76 yellow glaze and domestic coral red glaze were sifted and fired in two separate passes. Finally, two circular masks were overlapped and placed on the left and right sides, blue glaze was sifted to create a slight gradient effect, and the piece was fired. As long as suitably shaped masks can be found, this method can produce patterns of various shapes; with multiple layers of overlay, a wide range of effects can be achieved. Experimentation during the creative process can continually expand the possibilities.

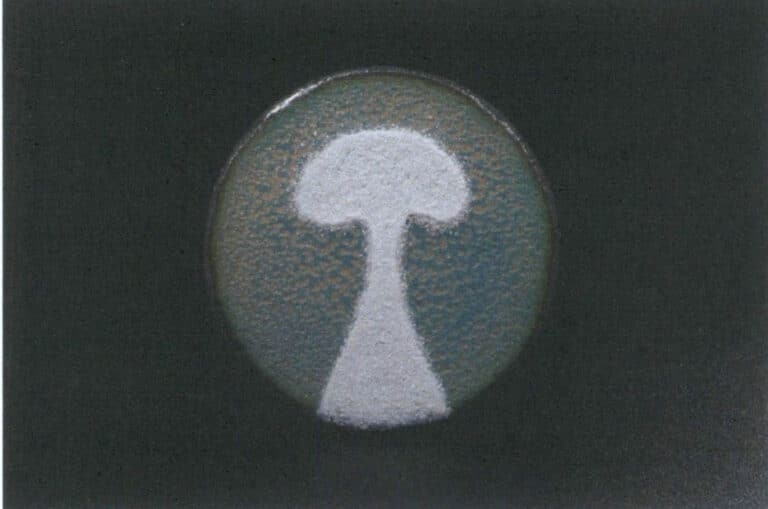

The melting of enamel glaze does not occur instantly; it goes through a process from powder to granules and then to liquid. Taking advantage of this characteristic of the glaze, when applying glaze by the dry-sifting method, opaque glazes can be fired to a semi-melted granular state. At this point, the enamel surface shows a matte, velvety effect, as in the work shown in Figure 9–12. The specific procedure is to fire a layer of transparent ground glaze on a copper base, then thinly sift a layer of domestically produced Chinese Cloisonné soft green glaze, and fire at a kiln temperature of 820 °C, as shown in Figure 9–13.

Carve the shape of the mushroom on the cardboard used to mask the work, sift on the porcelain white glaze—note that this layer should be sifted rather thick, as shown in Figure 9–14.

Figures 9–11 Tiling pattern of complex edges

Figure 9–12 Mushroom No. 17

Figure 9–13 Firing soft green ground

Figure 9–14 Sieving and applying mushroom-like porcelain-white glaze

2. Transparent Base Glaze Outlining Method

A transparent, colourless copper-base glaze is a rather special type of glaze. Besides serving as a transparent base glaze, it also helps prevent metal oxidation. If transparent base glaze is applied locally on a copper base plate, the unglazed areas will oxidise to black during firing, while the glazed areas will still show the original colour of the copper base plate.

This section describes a special technique that takes advantage of the properties of transparent base glazes. Before firing, part of the transparent base glaze is scraped away to expose the copper substrate; after firing, this produces two colours: the original copper tone and an oxidised black. Then a layer of another transparent colour is applied over it, resulting in natural and interesting dark traces beneath the transparent colour glaze. These traces can be lines or patches, depending on the shape of the removed base glaze. The work shown in Figure 9–16 was made using the transparent-base glaze outlining method: the mountain-shaped lines display a beautiful dark red, with varying depths of colour and naturally varying line shapes and widths.

The specific operating steps are as follows.

STEP 01

Soak the metal base plate in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water for later use.

STEP 02

Apply a layer of transparent base glaze to the back and fire it in a kiln at 850°C.

STEP 03

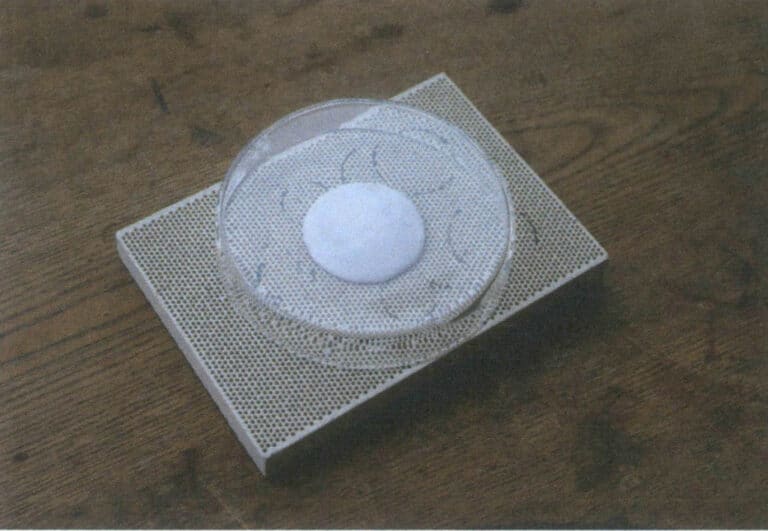

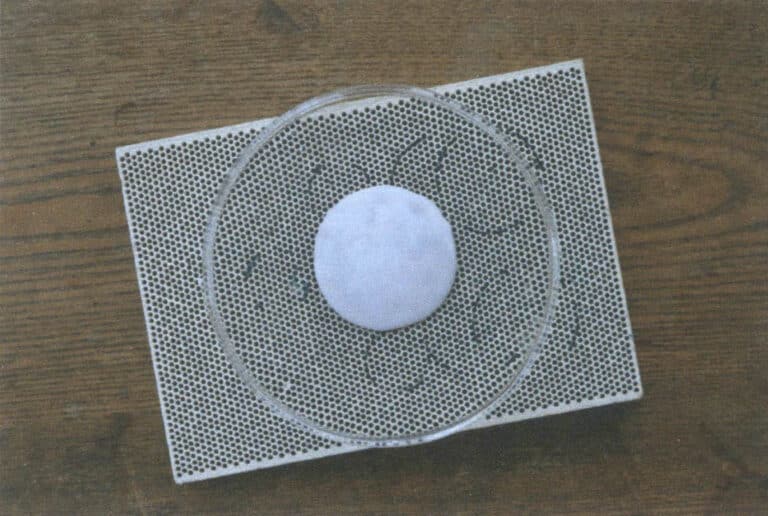

Spread a layer of transparent base glaze on the front, about 0.5 mm thick; take care not to make it too thick. Place the piece inside a glass dome to dry the moisture, as shown in Figure 9–17.The purpose of the glass cover is to prevent dust from falling onto the glaze surface.

STEP 04

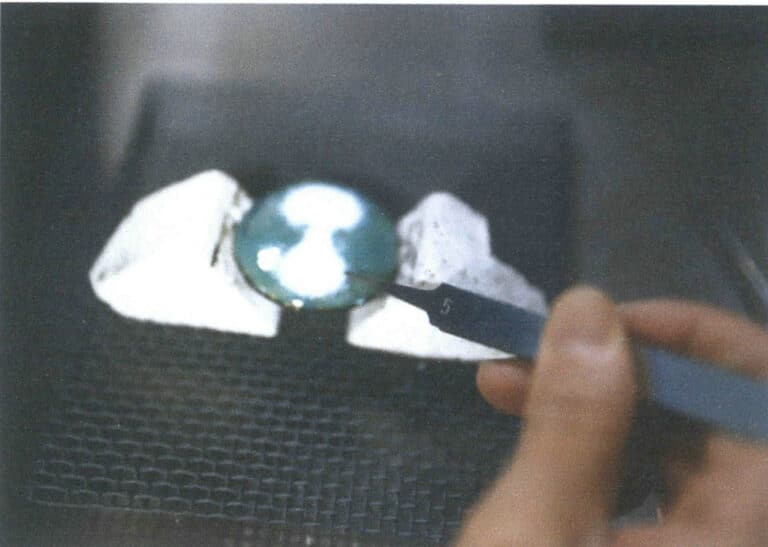

When the transparent base glaze on the front is almost dry, use a needle tip to remove the unwanted transparent base glaze according to the design, then fire it in a kiln at 850°C. The base glaze shown in Fig. 9-18 already has the required lines removed with a needle tip.

Figure 9–17 Place the piece inside a glass cover to dry

Figure 9-18 Removed required lines

STEP 05

After firing, the parts of the metal base plate where the glaze was removed turn black due to oxidation, while the glazed parts remain a bright copper colour, as shown in Fig. 9-19. On this basis, continue to apply a layer of transparent glaze, such as transparent blue, transparent green, transparent red, or any other transparent glaze, as shown in Fig. 9-20.

Figure 9–19 Parts that oxidised and blackened after firing when the glaze was removed

Figure 9–20 Applying a layer of transparent glaze

STEP 06

Sprinkle small pieces of gold leaf on the surface and fire in a kiln at 850°C. Figure 9–21 shows the completed piece.

Notes

(1) When scraping lines, the moisture content in the transparent base glaze is very important. If there is too much moisture, the glaze removed by the needle tip will rejoin due to the water and will not form a clear boundary; conversely, if there is too little moisture, the glaze will be in an almost dry powder state and will also be unable to produce a clear boundary.

(2) After removing the glaze and firing, the scraped areas turn black or dark red; this is the copper substrate exposed, where there is no transparent base glaze being oxidised. Be sure never to soak the piece in acid, as is sometimes done, otherwise the oxidised black and dark red textures will disappear.

3. White Base Glaze Marbling Method

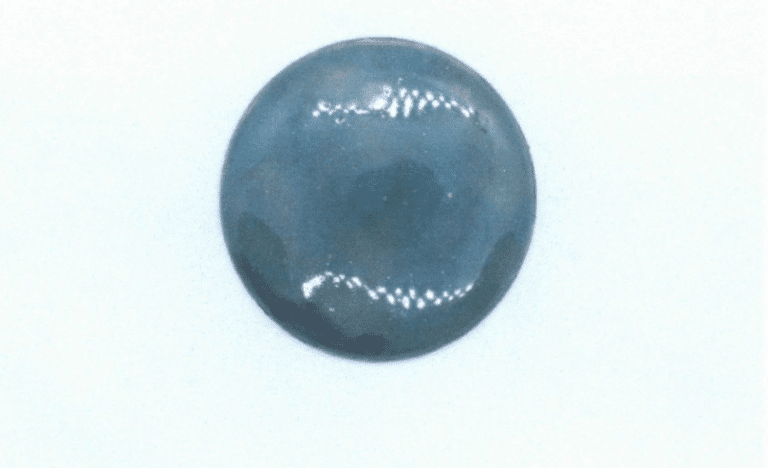

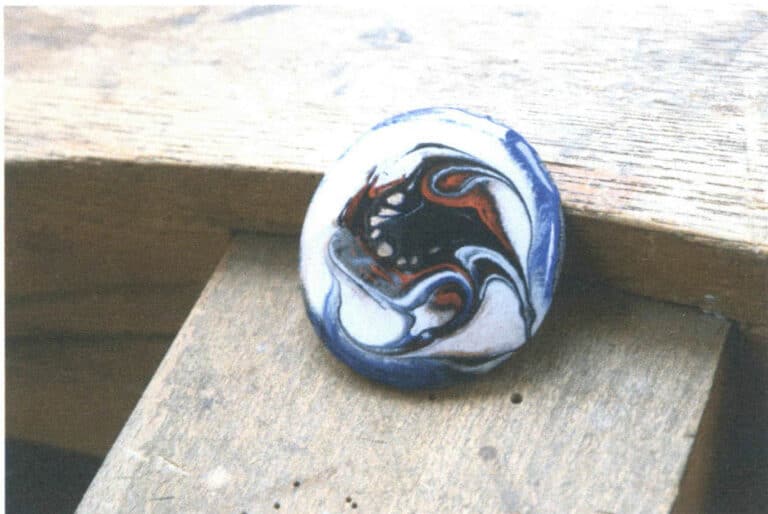

Strictly speaking, the melting temperature of each type of enamel glaze is not the same. The melting temperatures of transparent and opaque glazes differ by about 30~50 degrees Celsius, and the melting temperatures also vary among individual transparent glazes and among individual opaque glazes. The special technique described below takes advantage of this property of enamel glazes — using the differences in melting temperatures between different glazes to layer different colored glazes so that, after high-temperature firing, interesting and irregular marbling effects appear.

The craft example shown below demonstrates the marbling effect achieved by applying other colours over a white base glaze; using another base colour is also feasible, but the glaze thickness and firing temperature will differ and will require repeated experiments to achieve satisfactory results.

The specific steps for the white-base glaze marbling method are as follows.

STEP 01

Soak the metal substrate in a diluted sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water and set it aside.

STEP 02

Apply a transparent base glaze to the back and fire it in a kiln at 850 °C.

STEP 03

Apply a slightly thicker white glaze to the front, as shown in Figure 9-22. Here, the porcelain-white from Chinese Cloisonné glazes was chosen; other brands of white glaze or other opaque glazes can be used instead. Fire in a kiln at 810 °C.

STEP 04

Apply a thin layer of another glaze colour over the fired white glaze; it can be one colour or several, applied freely or according to a design, as shown in Figure 9-23.

Figure 9-22 Applying a slightly thicker white glaze

Figure 9-23 A thin layer of other glaze applied over the fired white glaze

STEP 05

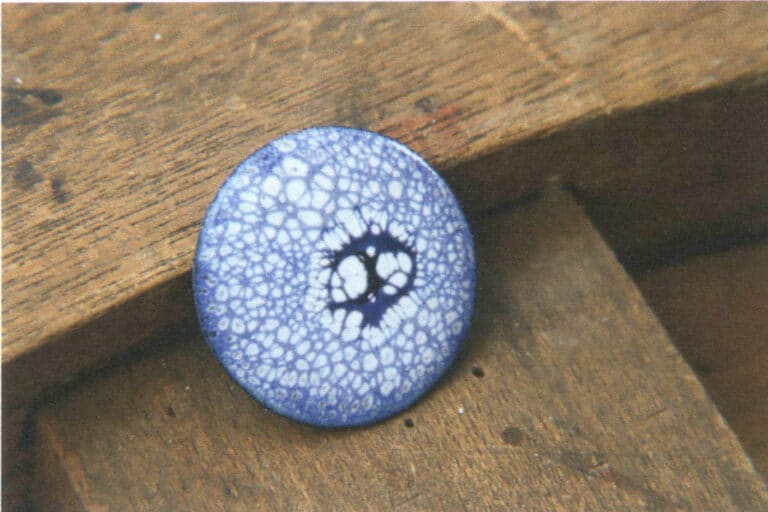

Place the piece into the kiln and fire it at a temperature of 900°C. When the temperature reaches 900°C, the lower layer of glaze will bubble up to the surface like boiling water. After removal and cooling, the enamel glaze surface will display a marbled effect with droplet-like, colorful patterns, as shown in Figure 9-24.

Notes

(1) The first layer of white glaze on the front should be thicker, and the second layer of colored glaze should be thinner; this helps produce a clear marbling pattern effect.

(2) Different colored glazes produce different marbling effects. Some can turn into large, very obvious patterns; some produce fine, dense patterns; and some colours show no obvious marbling effect even when fired to 900°C… Which specific colours yield which patterns must be determined through repeated testing.

4. Tread Drawing Technique

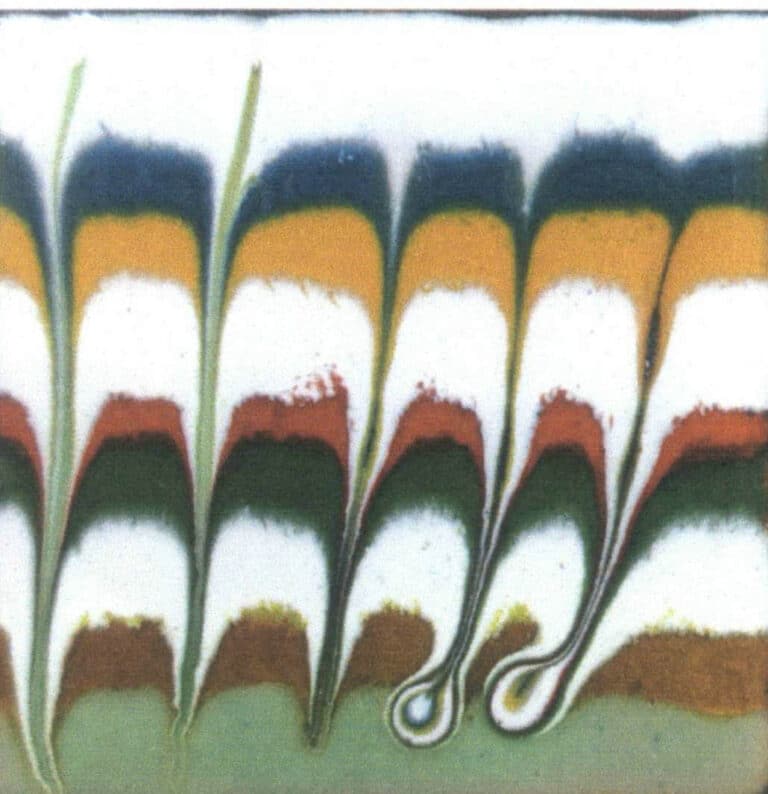

The tread drawing technique takes advantage of enamel glazes melting into a liquid state at high temperatures. The “tread drawing” method uses special tools to draw on the glaze while it is in a molten state, allowing different colored glazes to mix together in that state and form special patterns. The effect shown in Fig. 9-25 was created using the tread drawing technique.

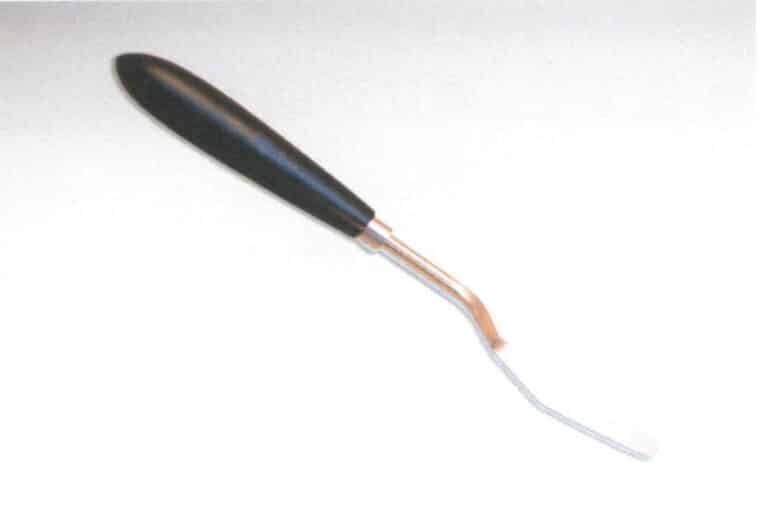

The tread drawing method requires a special tool — a steel rod long enough, with a diameter of 5~10 millimetres and a length of about 50 centimetres; bend it about 5 centimetres from the tip, grind the tip to a point, and fit the other end with a handle for easy gripping, as shown in Figure 9–26.

Figure 9–25 Presentation effect of the tread drawing method

Figure 9-26 A special tool for tread drawing

The specific operating steps of the tread drawing technique are as follows.

STEP 01

Soak the metal base plate in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water and set it aside.

STEP 02

Fire the back glaze and base glaze on the back and front of the metal base.

STEP 03

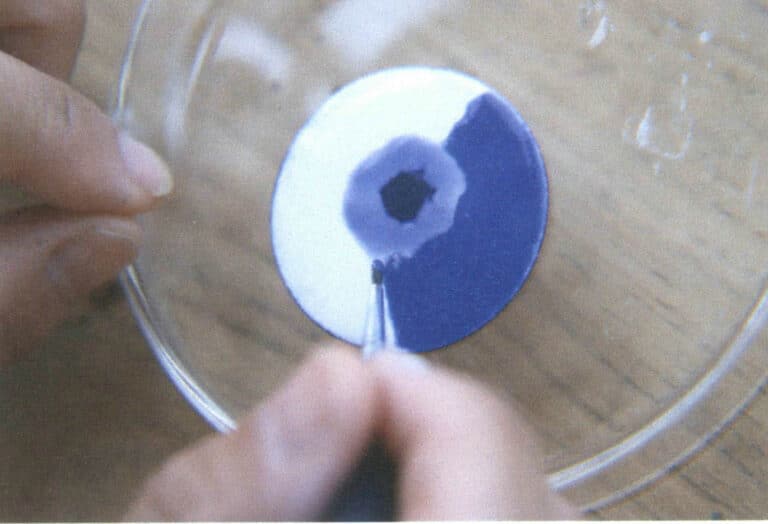

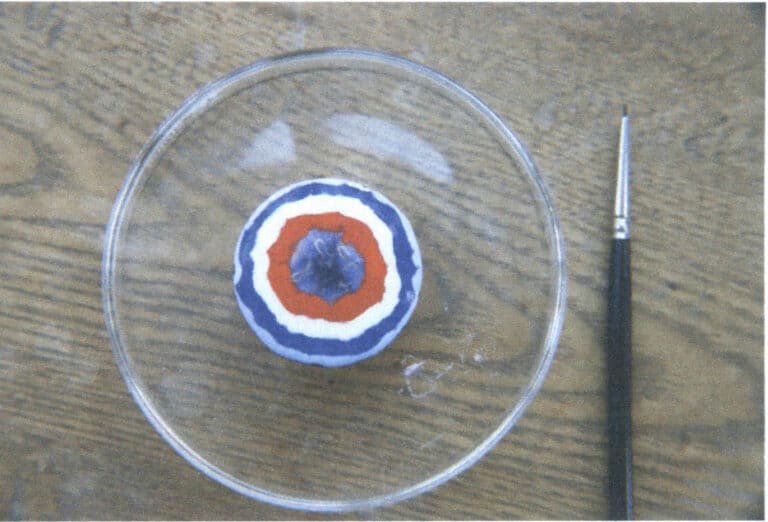

On the front of the piece, apply two or more different colored glazes according to the design, with the requirement that the layer be slightly thicker. When using the tread drawing technique, opaque glazes are generally chosen, as the effect will be more pronounced. The piece shown in Figure 9-27 used French No. 194 transparent deep purple glaze, Chinese cloisonné coral red glaze, Chinese cloisonné porcelain white glaze, and French No. 27 deep blue transparent glaze, arranged concentrically in irregular circular patterns from the centre outward.

STEP 04

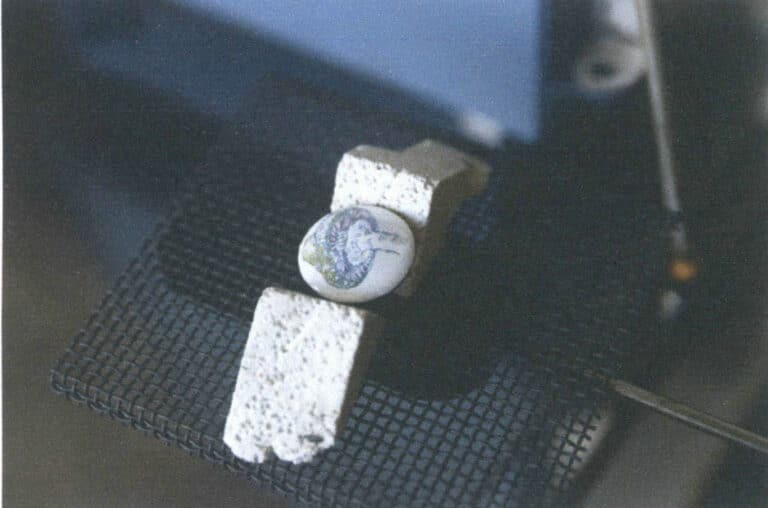

Please place it in the kiln and fire at a kiln temperature of 900°C. When the glazes have reached a fully melted state, open the kiln door and, using a special tool inserted into the kiln, draw a spiral pattern from the centre outward, as shown in Figure 9-28.

Figure 9-27 Applying the glaze for the pattern

Figure 9-28 Thread drawing in the kiln

STEP 05

Close the kiln door and fire again to 900°C. Figure 9-29 shows the completed piece.

Notes

(1) When the glaze melts, and patterns are drawn with a steel hook, they are generally sketched radially or in a spiral from the inside outward, or back and forth, left-right and up-down. Be careful not to break the boundaries between different colored glazes so that attractive patterns can form.

(2) The drawing motion should be as quick as possible; otherwise, once the kiln temperature drops, the glaze will congeal.

(3) When making works using the tread drawing technique, it is easier to operate with a large enamel kiln. Because a small enamel kiln has a relatively small heat capacity, once the door is opened, the temperature will drop rapidly and then struggle to rise to the target 900 degrees Celsius. When the temperature is insufficient, the tread drawing effect will be affected.

(4) There are two commonly used methods for doing tread drawing: one is the method described above, using a tool long enough to reach into the furnace to draw on the work; the other is to forgo an enamel kiln and melt the glaze with a blowtorch, then draw with some sharp tool while the glaze is molten. The advantage of this method is that it is easier to observe and manipulate, and does not require specialised tools.

5. Pencil Drawing

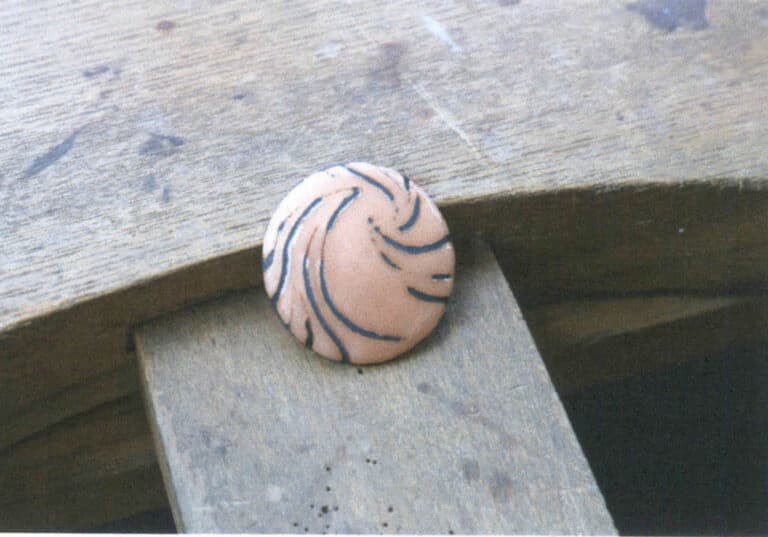

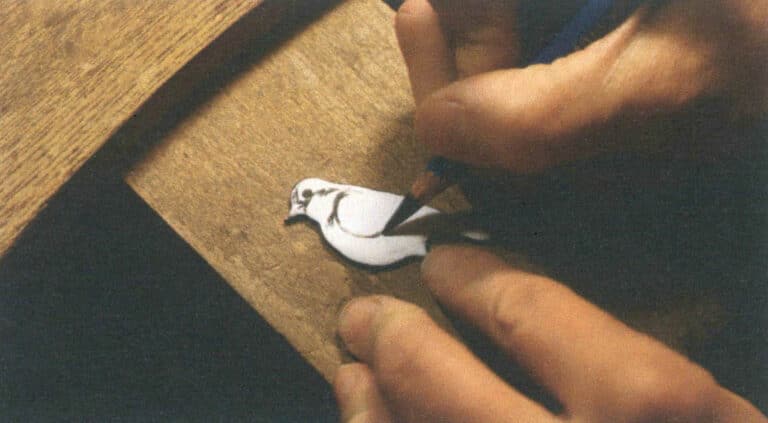

Pencil drawing refers to using the characteristic of pencil powder, which is able to withstand high temperatures around 760°C and fuse with the glaze. On a light-colored base glaze, a design is drawn with pencil, producing an effect similar to a sketch or pencil study.

The method for making pencil drawings is similar to making painted enamel. First, an opaque glaze is fired onto a copper plate to create the ground colour. After the ground is fired, the enamel surface needs to be roughened with an polishing oil stone— that is, abraded to a matte, non-reflective finish—because pencil cannot leave marks on a smooth glazed surface. Only after roughening can the design be drawn with a pencil on the glaze. After the drawing is finished, it is fired at a set temperature of 760°C; the pencil-applied design is fixed to the glaze surface by the high-temperature firing, and the glaze surface will be restored to a smooth, even state, completing the piece.

Because the glaze surface must be roughened before pencil drawing can be applied, the design can only be drawn and fired once; additions or modifications cannot be made after the first firing, since the glaze will have become smooth and it will be impossible to draw on the surface with pencil again—unless the glaze is roughened again with an polishing oil stone, but doing so would also abrade away the pencil design from the first pass.

Because the pencil drawing technique requires the composition to be completed successfully in a single pass, it is not suitable for depicting scenes with very complex layers or tones. If compared to drawing techniques such as sketching and quick studies, pencil drawing is closer to sketching.

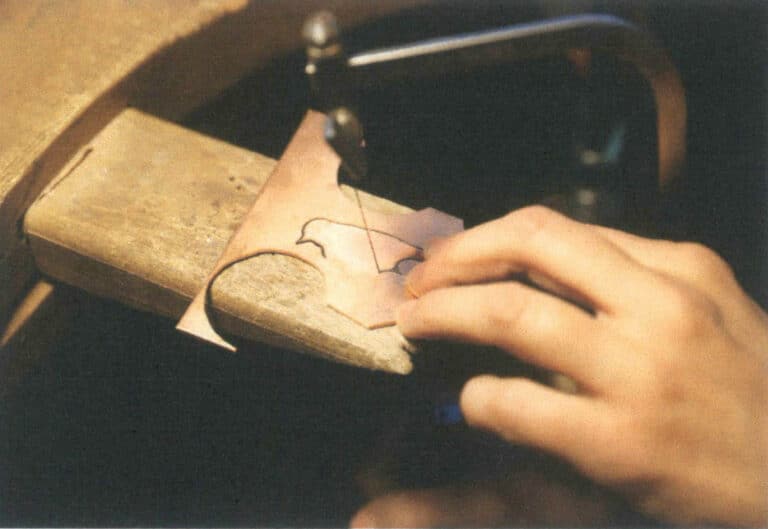

The specific production method for pencil drawing is as follows.

STEP 01

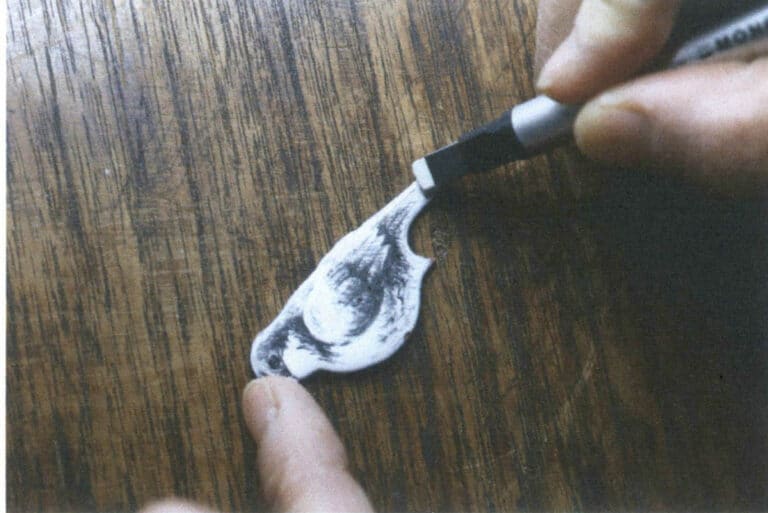

Saw the copper plate to the appropriate shape according to the design on a 1 mm thick copper sheet, as shown in Figure 9-30. File and dress the edges of the sawn copper base neatly, anneal it, then pickle it in acid for later use.

STEP 02

Apply a bright white glaze to the back of the copper base as a back glaze, set the kiln temperature to 850 °C and fire it; Figure 9–31 shows the piece with the bright white back glaze fired.

STEP 03

Apply a light opaque glaze to the front of the piece as the base colour — for example, white, off-white, beige, or light blue — choosing according to personal preference or design needs. In the production example, the porcelain-white from the Chinese cloisonné glazes was used, set to fire at 810 °C. Because the base glaze functions like a sheet of paper, it must be very smooth and uniform in colour; if one layer of glaze does not evenly cover the copper base, two firings are required, and using the dry-sieving method may even require three firings. The fired porcelain-white base glaze is shown in Figure 9–32.

Figure 9-31 Firing the bright white back glaze

Figure 9-32 The fired porcelain white base glaze

STEP 04

Use an polishing oil stone to sand the glaze surface into a rough frosted-glass texture. Choose a rectangular polishing oil stone, lay it flat against the glaze surface and sand in circular motions, as shown in Figure 9–33. Sand while observing the surface reflections; when all reflected spots on the glaze surface have disappeared, the base plate has been sanded to a rough surface and can be drawn on with a pencil. Figure 9–34 shows the sanded base plate.

Figure 9–33 Grinding the porcelain-white ground glaze with an polishing oil stone

Figure 9–34 Ground panel prepared for drawing

STEP 05

Use an 8B pencil to draw the design on the ground porcelain-white panel that has been roughened, as shown in Fig. 9–35.

STEP 06

After the pattern painting is completed, set the kiln temperature to 760 degrees Celsius for firing. Figure 9-36 shows the finished piece after firing.

Figure 9–35 Drawing the design with an 8B pencil

Figure 9-36 Finished piece after firing

Notes

(1) Because firing can only be done once, all patterns on the surface must be drawn completely before firing; they cannot be modified afterwards. This requires the maker to have an accurate prediction of the final effect during the creation process. Figure 9-37 shows a pencil drawing with very good control of black-and-white tones.

(2) If modifications are needed during the drawing process, localised, lighter pencil marks can be erased with a rubber eraser, as shown in Figure 9-38. Parts that cannot be removed with an eraser can be wiped away with turpentine or gently rubbed off with an polishing oil stone.

Figure 9-37 Pencil drawing

Figure 9-38 Erasing pencil marks that need modification with a rubber eraser

(3) Pencil drawings must be made using a high-quality 8B drawing pencil; the example uses Faber-Castell’s 8B drawing pencil. Pencil marks will become somewhat lighter after firing. Figure 9-39 shows a comparison of a pencil drawing before and after firing; you can see the overall image has lightened somewhat. For this reason, you can deliberately deepen the darkness of the drawing during creation so that after firing, the tones will be appropriately balanced.

(4) The firing temperature for pencil drawings must not be too high; the kiln is generally set to 760 °C for firing. If the temperature is too high, the pencil marks will noticeably fade or even disappear. Figure 9-40 shows a pencil drawing fired at too high a temperature; you can see the design has become very faint, nearly vanished.

Figures 9–39 Comparison before and after firing

Figure 9–40 Pencil drawings with glaze fired at excessively high temperature

6. Use of Glaze Granules and Glaze Threads

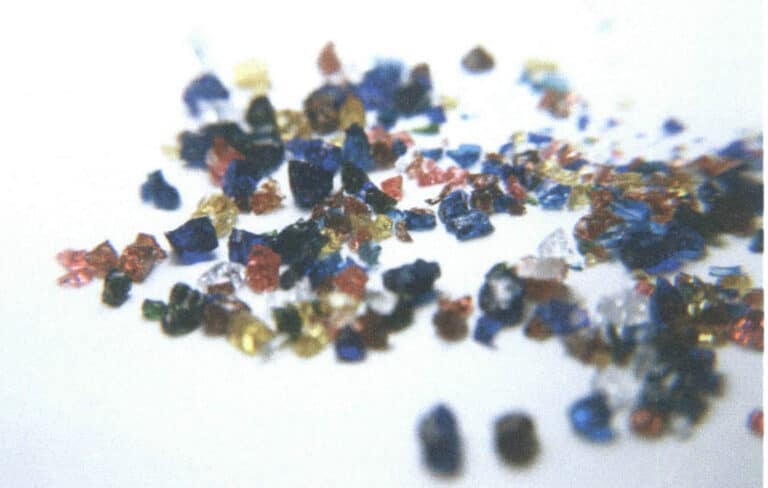

Figur 9-41 Glasurgranulat

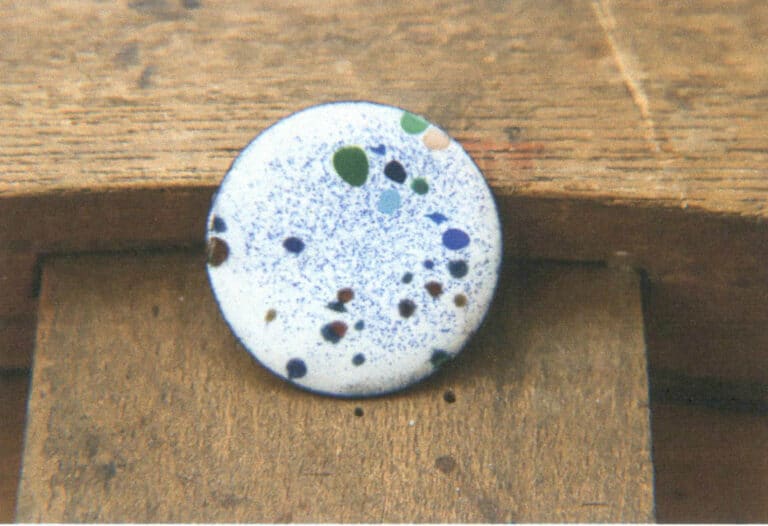

Figure 9-42 Interesting effects formed by glaze granules

Figure 9-43 Glaze threads

Figure 9-44 Effect after firing glaze threads

The specific steps for using glaze granules or glaze threads are as follows (taking glaze granules as an example).

STEP 01

Soak the metal base plate in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water and set it aside.

STEP 02

Apply a transparent base glaze to the back of the metal base plate, then fire in a kiln at a temperature of 850 °C.

STEP 03

Apply a layer of transparent base glaze to the front of the metal backing and fire it in a kiln at a temperature of 850°C.

STEP 04

Apply the base glaze according to the design requirements; it can be a single colour or multiple colours, and it is best to choose a glaze that is relatively kiln-stable. The example shown in Fig. 9-45 is French opaque blue sifted over domestically produced cloisonné porcelain white glaze, with the kiln temperature set to 820°C for firing.

STEP 05

Scatter glaze granules over the fired base glaze surface and fire again; Fig. 9-46 shows the finished piece.

Figure 9-45 Blue glaze sifted over porcelain white base glaze

Figure 9-46 Finished work

Notes

When using powdered glaze granules, choose smaller granules; granules that are too large are difficult to melt, and prolonged firing may damage the base glaze.

7. Use of Gold Leaf and Silver Leaf

Leaf (gold or silver) has two uses in the enamel craft: one is to lay the leaf as an underlay at the bottom, over which glaze is applied and fired; the other is to apply the leaf to the surface of a finished piece. These two methods serve different purposes and produce completely different visual effects.

Taking gold leaf as an example, one method is to apply the gold leaf at the very bottom and then cover it with other transparent glazes; the final colour effect of using gold leaf in this way is not a gold colour but the effect of firing transparent colours over a gold base. In addition, when the gold leaf is covered beneath the glaze, the glaze’s shrinkage during high-temperature firing causes the gold leaf to form fine wrinkles. Due to the principle of diffuse reflection of light, the wrinkles of gold leaf beneath a transparent glaze create a gorgeous shimmering effect, similar to the effect of metal ground patterns in basse-taille enamel. The sunflower petals on the cloisonné enamel work “Growing Toward the Sun”, shown in Figure 9–48, were made by applying gold leaf on a silver base and covering it with two transparent yellow glazes, French No.15 and No.30, and firing them.

Another method is to, after all colour layers have been fired and the piece has been polished, clean the work in an ultrasonic cleaner and, before the final firing for colour brilliance, apply gold leaf to the designed locations; after the final colour firing, the gold leaf is firmly adhered to the surface of the glaze. Using this method to attach the leaf, because no glaze covers the gold leaf, the surface of the gold leaf is smooth and flat, its colour is that of gold, producing a strong decorative effect, and the gilded areas become the highlights of the entire piece. For example, in the cloisonné enamel work “Cui” shown in Fig. 9-49, the three dots along its axis have gold leaf applied to their surfaces.

Figure 9-48 Cloisonné enamel work "Growing Toward the Sun"

Figure 9-49 Cloisonné enamel work "Cui"

The specific steps for applying gold leaf are as follows (in the example, the leaf is applied to the base of the cloisonné enamel piece, materials: silver base plate, silver wire, gold leaf).

STEP 01

Immerse the metal base plate in a dilute sulfuric acid solution for cleaning; after about 15 minutes, remove it and rinse thoroughly with running water for later use.

STEP 02

On the front of the piece, place the shaped silver wires on one side and spread transparent base glaze on the other, then fire in a kiln at 850°C; see Chapter 5 for detailed methods of cloisonné wire placement and arrangement.

STEP 03

Apply transparent base glaze to the back of the metal base plate and fire in a kiln at 850°C.

STEP 04

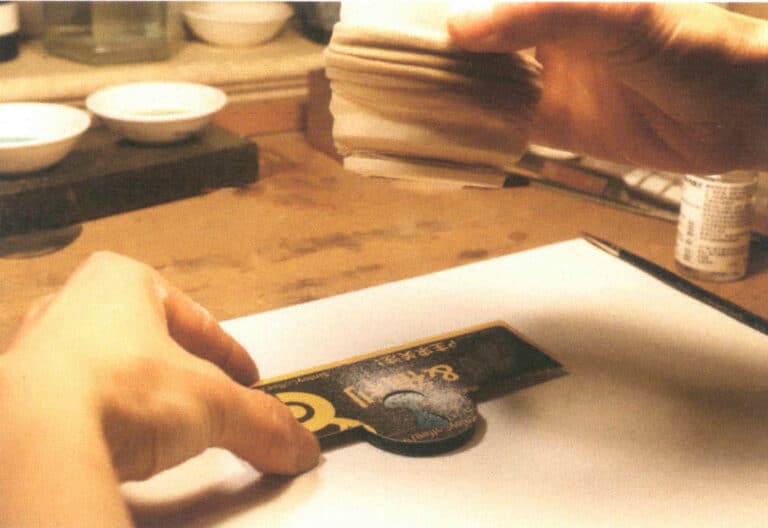

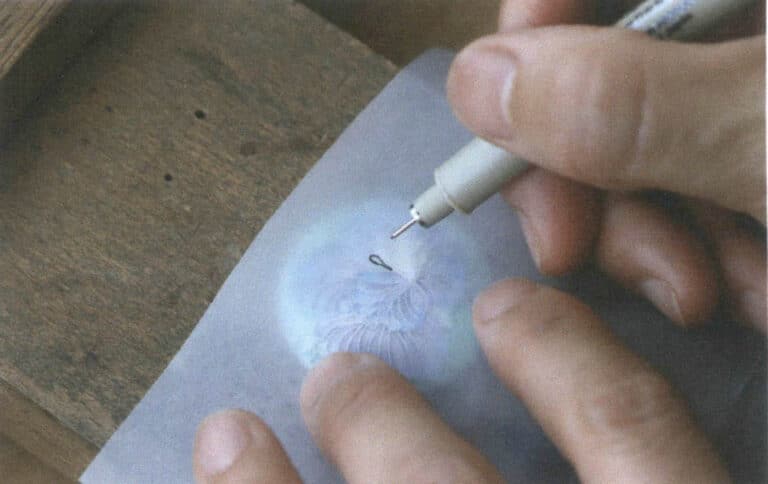

Cover the area where foil is to be applied with semi-transparent tracing paper and accurately trace the shape of the area to be foiled with a pen, as shown in Figure 9-51.

STEP 05

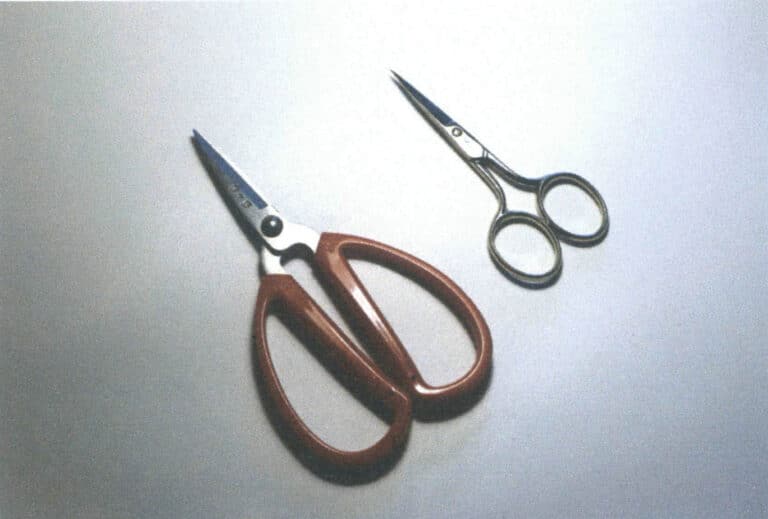

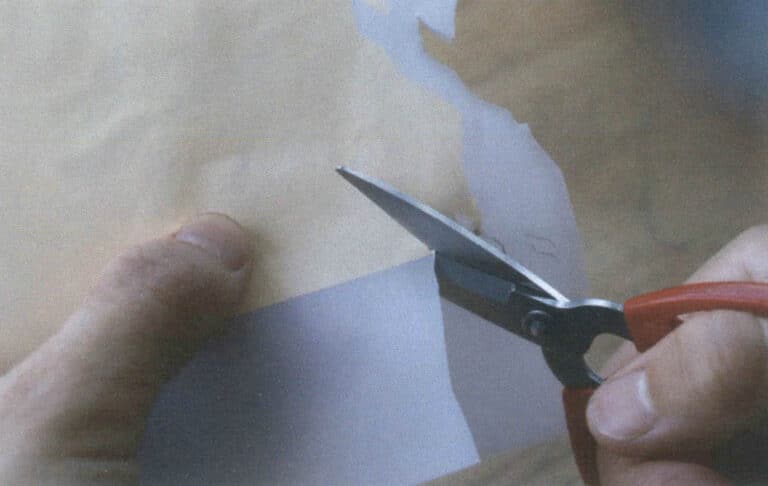

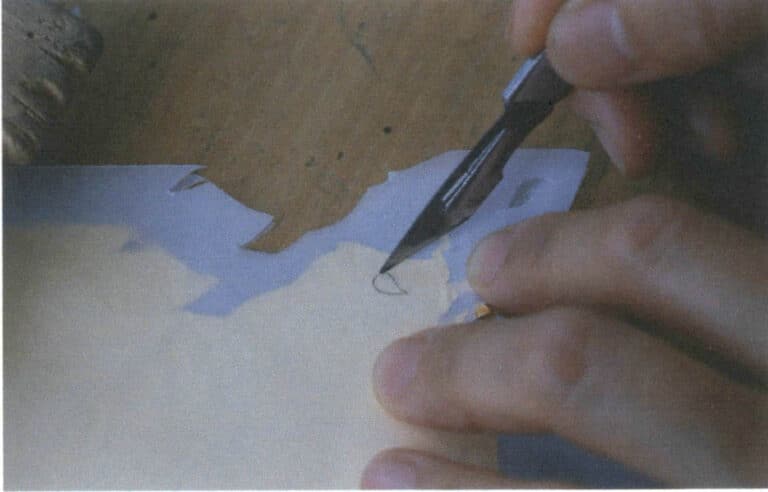

Place the tracing paper with the drawn pattern over the gold leaf and cut along the lines with sharp, small scissors, as shown in Fig. 9-52; you can also use a carving knife on a cutting board, as shown in Fig. 9-53. Scissors are suitable for larger, simpler-shaped patterns, while a carving knife is suitable for more complex, finer designs.

Figure 9-52 Cutting gold leaf

Figure 9-53 Carving gold leaf

STEP 06

Apply a layer of enamel adhesive to the enamel surface where the foil will be applied. Use the glue-brushing pen to gently pick up the cut-to-shape gold leaf and place it where needed, as shown in Figure 9-54. While the enamel adhesive is still wet, you can make slight position adjustments; use the brush to gently tap down on the surface of the gold leaf to ensure it adheres closely to the enamel surface. The gold leaf in the flower centre shown in Figure 9-55 has already been applied.

Figur 9-54 Plukke opp bladgull med en limpensel

Figure 9-55 Flower centre with gold leaf applied

STEP 07

Fire the enamel piece with the applied gold leaf in the kiln, setting the temperature according to the melting temperature of the glaze layer beneath the gold leaf. After this firing, the gold leaf will be firmly bonded to the underlying enamel layer.

Notes

(1) The gold leaf required for enamelling should be 4 micrometres thick, which is much thicker than the gold leaf commonly used in lacquerware or woodworking. Therefore, when purchasing gold leaf, be sure to confirm with the seller whether it is specifically intended for enamelling.

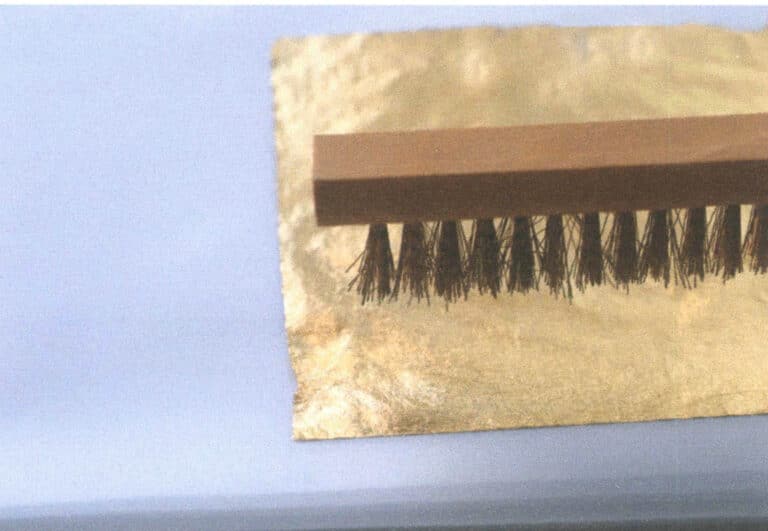

(2) The purchased gold leaf must be pretreated before use. The method is to lay the gold leaf flat on a relatively soft paper and gently tap it from top to bottom with a brush; the brush will produce fine, evenly distributed tiny holes on the surface of the gold leaf, as shown in Figure 9-56. Move the brush position evenly and slowly, continuing to tap until tiny holes cover the entire sheet of gold leaf. Hold the treated gold leaf up to a light source to observe the uniformly distributed fine holes, as shown in Figure 9-57. Store the treated gold leaf properly between two sheets of tracing paper for future use. Pretreating the gold leaf is necessary because when the piece is fired in the kiln, the adhesive used to attach the leaf will release gases at high temperature; these tiny holes serve to vent the gases beneath the gold leaf. If gas accumulates under the gold leaf, it will cause blistering and affect the adhesion between the gold leaf and the enamel surface.

Figure 9-56 Tapping the gold leaf with a brush

Figure 9-57 The treated gold leaf covered with fine holes