What Is Enamel? A Beginner’s Guide To High-Temperature Enamel For Jewelry Making

Introduction to Enamel Craft: A Complete Guide to Glazes, Metals & Basic Techniques

Introduction :

This chapter will briefly introduce the origins and development of the enamel craft, analyze the crucial raw material components and properties in the enamel process, and introduce the types of metals that can be used to fire enamel.

Enamel Glaze Test Samples

Table des matières

Section I The Origins and Development of the Enamel Craft

There are a few articles and resources on enamel techniques on domestic websites, and most of the material is fragmented and unsystematic, containing many errors and vague statements; even within the same article, there are often contradictions. Common misconceptions about enamelling mainly concern the origin of enamel, the composition of enamel glazes, the characteristics of enamel techniques, and their historical emergence. For example, many articles claim that enamel glazes are made by grinding natural gemstones into powder, whereas the main component of enamel glaze is silica (SiO2), similar to glass; many articles also conflate high-temperature enamel with cold enamel, even though they are different materials, or confuse painted enamels used in enamelling processes with enamel-like decoration applied to porcelain.

A careful analysis of these erroneous claims shows that most of them stem from a Lack of understanding of the history of enamel and the basic processes of enamelling. Therefore, this chapter first gives a basic overview of the origin and development of enamelling, then provides a detailed introduction to the basic components and properties of enamel glazes, as well as several metals that can be used for firing enamel.

1. Origin of the Enamelling Craft

The origin of a craft can be determined through excavated artefacts. Thus, when discussing the time and place of origin of a craft, research and conjecture are often based on known artefact evidence. It should be noted that such conclusions are not fixed and need to be updated in light of the latest archaeological discoveries.

The origins of enamel and the development of enamelling covered in this book, including the periods when various enamelling techniques appeared, are all derived from existing physical artefact evidence.

Some researchers believe that enamelling first appeared in ancient Egypt; this involves the basic concept of enamelling. In both ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, there was a technique similar to enamelling that combined glass with fine metalwork. Sometimes this technique inlaid colored glass and semiprecious stones into metal; other times grooves were first made in a metal base by chasing or other methods, and molten glass was poured into them so the liquid glass filled every corner of the grooves and solidified on the metal when cooled. This technique is undoubtedly closely related to later enamelling, and enamelling very likely developed from it. But it should be clarified that this technique is not enamelling in the strict sense used today; some call it a prototype of enamelling.

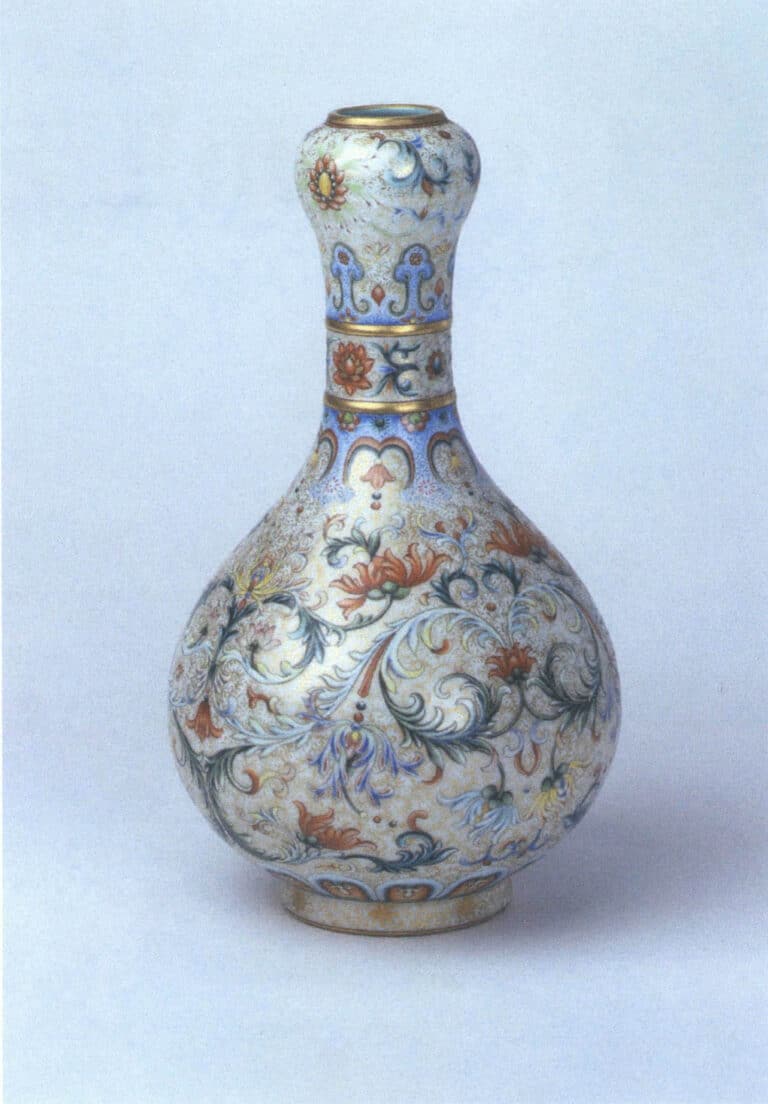

The earliest known and internationally recognised objects decorated with enamelling are six rings from the 13th century BCE, unearthed on the island of Cyprus, belonging to the Mycenaean civilisation. Figure 1–4 shows one of these rings; the surface is decorated with gold wires, and enamel was fired into the spaces between the wires. Due to the long passage of time, the enamel glaze has partially fallen away.

Also unearthed with these rings was an 11th-century BCE double-headed eagle sceptre, whose enamel section at the top has been relatively well preserved. The glass parts were fused directly onto the surface of the gold after melting, rather than being set into the metal surface, and thus this can be identified as true enamelling.

2. The Development of Enamelling Craft

From around the 6th century BCE in ancient Greece, people began combining enamel techniques with jewellery and goldsmithing. In Seville and Cádiz in Spain, Phoenician cultural items dating to around the 5th–4th centuries BCE have been unearthed that used enamel techniques.

A Greek author of the Roman era, Philostratus, mentioned when describing the Celts, Franks, Vikings, and Saxons that ” the barbarians from the north melt a kind of grey sand onto metal, which, when cooled, becomes a brightly colored and hard material, at that time used by warriors to decorate shields, horse armour, or helmets… They invaded the Roman Empire and brought this decorative craft to central Europe.” From the description in the book, this decorative technique closely resembles today’s enamel work; the sand’s main component is silicon dioxide, and ” melting the sand onto metal” implies heating the sand and metal together, or at least placing the sand on the metal and heating until it melts — that is, reaching the sand’s melting point — which aligns with the earlier definition of enamel.

In the region of Gaul in France, some objects dating to around the 3rd century BCE that used enamel techniques have been found, along with workshop remains for making enamelled objects and some tools; these are believed to have been left by the Celts and other nomadic peoples. Most enamels of that period were fired on bronze substrates, with a few fired on gold substrates.

Starting in the 11th century, enamelwork entered a period of vigorous development. From that time, Limoges in France became a very important region for enamelwork. Many enamel workshops and excellent enamelers gathered in the Limoges area, producing various enamel-integrated religious objects for royalty, nobility, and churches, such as crosses, icons, and reliquary boxes. It was precisely the large demand for religious objects at that time that drove the development of enamelwork. Figure 1–5 shows the decoration on a medieval reliquary box, fired with opaque glazes in black, white, blue, green, and other colours; it is now in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Limoges in France.

From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, craftsmen continuously improved existing enamel techniques and enamel glazes in the process of making works, inventing many new methods. For example, transparent glazes and champlevé enamel techniques, painted enamel glazes and painted enamel techniques, as well as cloisonné enamel techniques appeared.

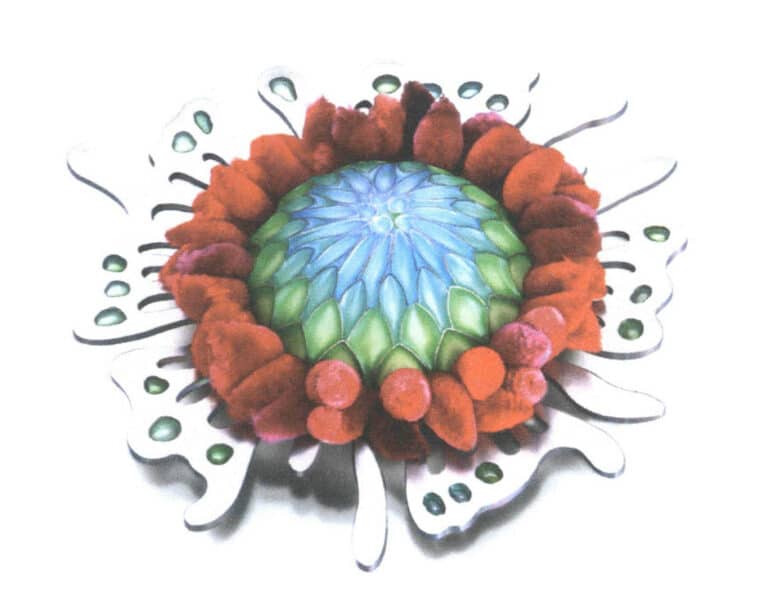

The Art Nouveau movement in Europe at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries was a very important period for enamelwork. During the Art Nouveau period, enamelwork was widely applied to jewellery. The fresh, natural design style of Art Nouveau, with themes inspired by fairies, insects, or plants, was very well suited to expression through enamelwork; design and craft complemented each other, producing a large number of exquisitely made, highly artistic jewellery pieces. In the Art Nouveau period, artists and craftsmen improved some enamel techniques through equipment and process changes, bringing enamelwork to a new peak. In this period it was common to see several different enamel techniques used on a single piece, greatly increasing technical difficulty and enriching artistic effect; additionally, cloisonné (openwork) enamel was widely used in Art Nouveau enamels: cast gold or silver frameworks supported thin, light-transmitting enamel layers that were delicate, lively, and brilliantly colored, especially suited to depicting fine, thin petals, insects, or fairy wings. Before and after the Art Nouveau period, no era produced such a large number of high-quality openwork enamel pieces. Figure 1–6 shows an Art Nouveau openwork enamel pendant in which the airy openwork enamel is perfectly combined with baroque pearls to cleverly reproduce the plant’s marvellous structure.

Enamel craftsmanship has been beloved since its inception and remains so today, frequently appearing in high-end jewellery, expensive watches, or modern art jewellery designs. When combined with precious gemstones, semiprecious stones, or precious metals, it emits a unique brilliance; it is also a technique much favoured by avant-garde experimental jewellery artists, as it can impart an extraordinary temperament and effect to a piece.

Section II Enamel Glaze

1. Composition and Production of Glaze

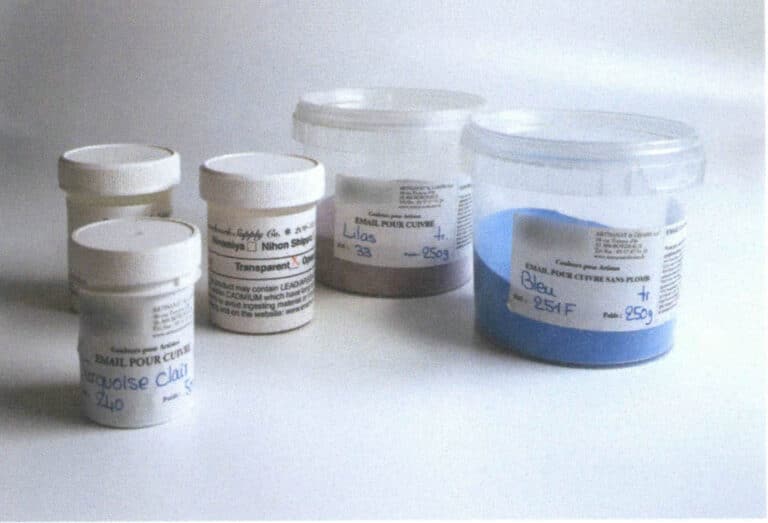

Figure 1–9 Enamel glazes produced in Japan

Figure 1–10 Domestically made cloisonné glazes

Copywrite @ Sobling.Jewelry - Fabricant de bijoux sur mesure, usine de bijoux OEM et ODM

2. Properties of Enamel Glaze

Regardless of the brand of enamel glaze, and even among different colours within the same brand, the fineness, cleanliness, and colour stability vary. Suppose the maker is very familiar with the properties of the glaze. In that case, the success rate of the work can be greatly improved, and even average-quality enamel glazes can be used to fire excellent enamel pieces.

In the actual production of enamel works, the glaze properties that the maker most needs to know and understand are the following: the final colour the glaze will present, the melting temperature of the glaze, the firing temperature of the glaze, the glaze’s firing resistance, and the glaze’s shrinkage rate.

(1) The final colour presented by the glaze. Enamel glazes show different colours before firing, during firing and after final firing. Except for some special techniques, the colours needed in creation are mostly the colours after final firing — that is, the colour presented when an enamel glaze has melted to its fullest extent and then cooled. When making standard colour swatches for glazes, the glaze needs to be fired to this degree — neither under- nor over-fired. Figure 1–14 shows the colour effect of a French-made transparent red glaze after it has fully melted.

(2) The melting temperature of the glaze. The melting temperature refers to the temperature required in the enamel kiln for the glaze to begin changing from a solid to a liquid. Theoretically, the melting temperature of each enamel glaze is not the same, but there are certain patterns. Broadly speaking, all opaque glazes have melting temperatures about 30°C lower than transparent glazes. Figure 1–15 shows a test piece arranged with a transparent green glaze, a transparent blue glaze, an opaque yellow glaze and an opaque white glaze. With the kiln set to 800°C and fired, you can see that the opaque yellow and opaque white glazes have fully melted, while the transparent blue and transparent green glazes have not yet completely melted.

Figure 1–14 Colour effect of a transparent red glaze after full melting

Figure 1–15 Comparison of melting states of different colored glazes fired at the same temperature

(3) Firing temperature of the glaze. When a glaze melts, it generally does not immediately show its final fired colour; after the start of melting, it requires a period of further heating for the glaze to fully melt. Without sufficient melting, the glaze cannot display the desired colour. The temperature required to bring the glaze to a fully melted state is the firing temperature of the glaze. Figure 1–16 shows the colour effect of the same transparent red glaze as in Figure 1–14 when it has not yet fully melted; by comparison, it is clear that the insufficiently melted glaze appears darker and does not achieve the ideal colour effect.

(4) Firing stability of the glaze. When a glaze is fired to its firing temperature—that is, when it reaches a fully melted state— and then cooled, it will show its intended colour. However, some glazes, once fully melted, will not change their final colour even if kept in the kiln for some additional time; examples include most transparent blue and transparent green glazes. These glazes can be considered relatively stable in firing. Other glazes, such as most transparent red series glazes, must be removed from the kiln and cooled quickly once they reach the fully melted state; otherwise, their final colour will be severely affected. These glazes have poorer firing stability. Most opaque glazes are less firing-stable than transparent ones; among transparent glazes, the red and yellow series are relatively less firing-stable. On the three test tiles shown in Figure 1–17, transparent green, transparent blue, transparent red and transparent yellow, opaque white, and opaque pink glazes were applied and fired at temperatures 15 °C above their firing temperatures. It can be observed that the colour effects of the transparent green and transparent blue glazes were not affected. In contrast, the transparent red and transparent yellow glazes became opaque, and the edges of the opaque white and opaque pink glazes began to shrink.

Figure 1–16 Colour effect of transparent red glaze when not fully melted

Figure 1–17 Comparison of firing stability for glazes of different colours

(5) Shrinkage of the glaze. Enamel glazes undergo a certain amount of shrinkage after firing; the degree to which they shrink is called the shrinkage rate. Because different brands of enamel glaze have varying shrinkage rates, it is best not to use two different brands of enamel glaze on the same piece unless experiments have been conducted. Since factory data for enamel glazes do not indicate shrinkage rates, the extent of glaze shrinkage can only be determined by firing test samples. Makers must be familiar with the shrinkage rates of the glazes they use in order to avoid problems arising from them.

3. Opaque Glazes and Transparent Glazes

Enamel glazes can be classified in various ways. For example, by translucency and color effects after firing, they can be divided into transparent glazes, opaque glazes, semi-transparent glazes, and pearlescent glazes; by composition, into lead-containing glazes and lead-free glazes; by melting temperature, into high-temperature, medium-temperature, and low-temperature glazes; they can also be classified according to the metals they are intended for—for instance, the Beijing Cloisonné Factory produces glazes categorized for use with silver and for use with copper.

In general, the commonly used enamel glazes can be divided into two main categories: transparent glazes and opaque glazes.

(1) Transparent enamels. Transparent enamels appear transparent after firing. Light passes through the enamel layer, strikes the metal substrate and reflects, so the colour after firing is determined jointly by the light, the enamel layer and the metal substrate. The same colored transparent enamel can look completely different when fired on different metal substrates. The thickness of the enamel also affects the fired result: the thicker the enamel, the lower the transparency and the deeper the colour. Figure 1-18 shows fragments of transparent enamel, from which their complete transparency can be seen.

Figure 1-19 shows a comparison of a transparent light-purple enamel fired on pure silver and on 24K gold substrates. Because the enamel itself is a transparent light purple, the final appearance is actually the colour produced by the overlay of the enamel colour and the metal substrate colour.

Figure 1-18 Fragments of transparent enamel

Figure 1-19 Comparison of a transparent light-purple enamel fired on pure silver and on 24K gold substrates

Completely colourless transparent glazes are special among transparent glazes. Completely colourless transparent glazes are often used as an underglaze that comes into direct contact with metal, because they prevent metal oxidation and can also improve the colour rendering of other glazes applied over them. Figure 1–20 shows a colourless transparent underglaze fired on a red copper substrate.

Figure 1–21 shows the effect when a bright white glaze begins to melt; you can see the copper substrate has been oxidized and turned black.

Figure 1–20 Colourless transparent underglaze fired on a red copper substrate

Figure 1–21 Effect when a bright white glaze begins to melt

As the temperature rises, the glaze continues to melt, gradually reducing the oxidized copper substrate back to the natural colour of copper. On the test piece shown in Figure 1-22, the transparent underglaze has mostly melted, and most areas of the copper substrate show a bright copper colour, with only some localized red or dark spots remaining; this condition indicates the glaze has not yet fully melted.

In the effect shown in Figure 1-23, the bright white glaze has reached a fully melted state, and you can see the red copper substrate has been entirely reduced back to the natural colour of copper.

Figure 1-22 Bright white glaze not fully melted

Figure 1-23 Bright white glaze fully melted

(2) Opaque enamels. As the name implies, opaque enamels appear non-transparent after firing; light cannot penetrate the enamel layer. Figure 1-24 shows fragments of opaque enamel, which are completely opaque; their colours also reveal the difference from transparent enamels.

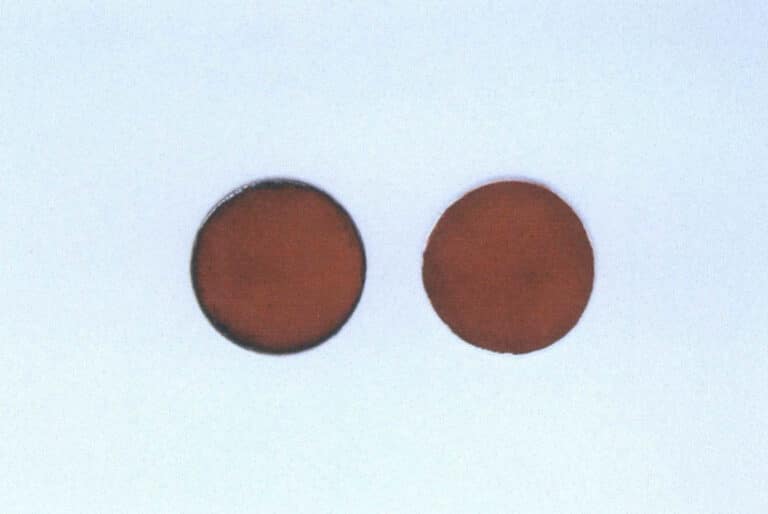

Because light cannot pass through the enamel layer, the metal substrate is concealed, and only the colour of the enamel can be seen. For this reason, opaque enamels are less often used on gold or silver substrates. In addition, opaque enamels can be applied directly to the metal substrate or directly onto a layer of transparent, colourless ground enamel, since opaque enamels have a lower melting temperature than transparent ones. Figure 1-25 shows a comparison of domestically produced cloisonné coral-red opaque enamel fired on copper and silver substrates; in terms of colour presentation, there is essentially no difference. The only distinction is that when fired on a copper substrate, a ring of copper oxide blackline forms at the glaze edge, which must be removed with acid cleaning or a diamond grinding bit.

Figure 1-24 Fragments of opaque enamel

Figure 1-25 Comparison of domestically produced cloisonné coral-red opaque enamel fired on copper (left) and silver (right) substrates

In general, because of differences in melting temperatures and other properties, opaque and transparent glazes should be avoided from being used together on the same piece whenever possible. But suppose special design requirements force the use of both transparent and opaque glazes on the same piece. In that case, the difference in melting temperatures must be taken into account during firing, and the differing firing durability of the opaque and transparent glazes must also be considered. When transparent and opaque glazes are combined on the same piece or even in the same area, they can sometimes cause problems that affect the firing outcome. Still, they can also occasionally produce unexpected, interesting special effects. Only through repeated testing can one grasp the patterns by which these special effects occur, and under the premise of achieving relatively stable and controllable results, truly apply these special effects in the creation of works.

Glaze powders are generally in powdered form, and their colours before and after firing are different, especially transparent glaze, whose pre- and post-firing colours are often completely different. For example, transparent red-series enamel powders are white before firing. Therefore, we cannot judge an glaze’s fired colour from the colour of its powder. After purchasing glaze, an important task is to fire glaze colour swatches to serve as references when selecting glazes for work. Figure 1-26 shows several glaze powders and colour swatches; the glaze used are French No. 621 transparent orange, French No. 40 transparent red, and French 300F opaque light pink. From this picture, there may be a very large difference between the colour of an glaze powder before firing and the colour after firing.

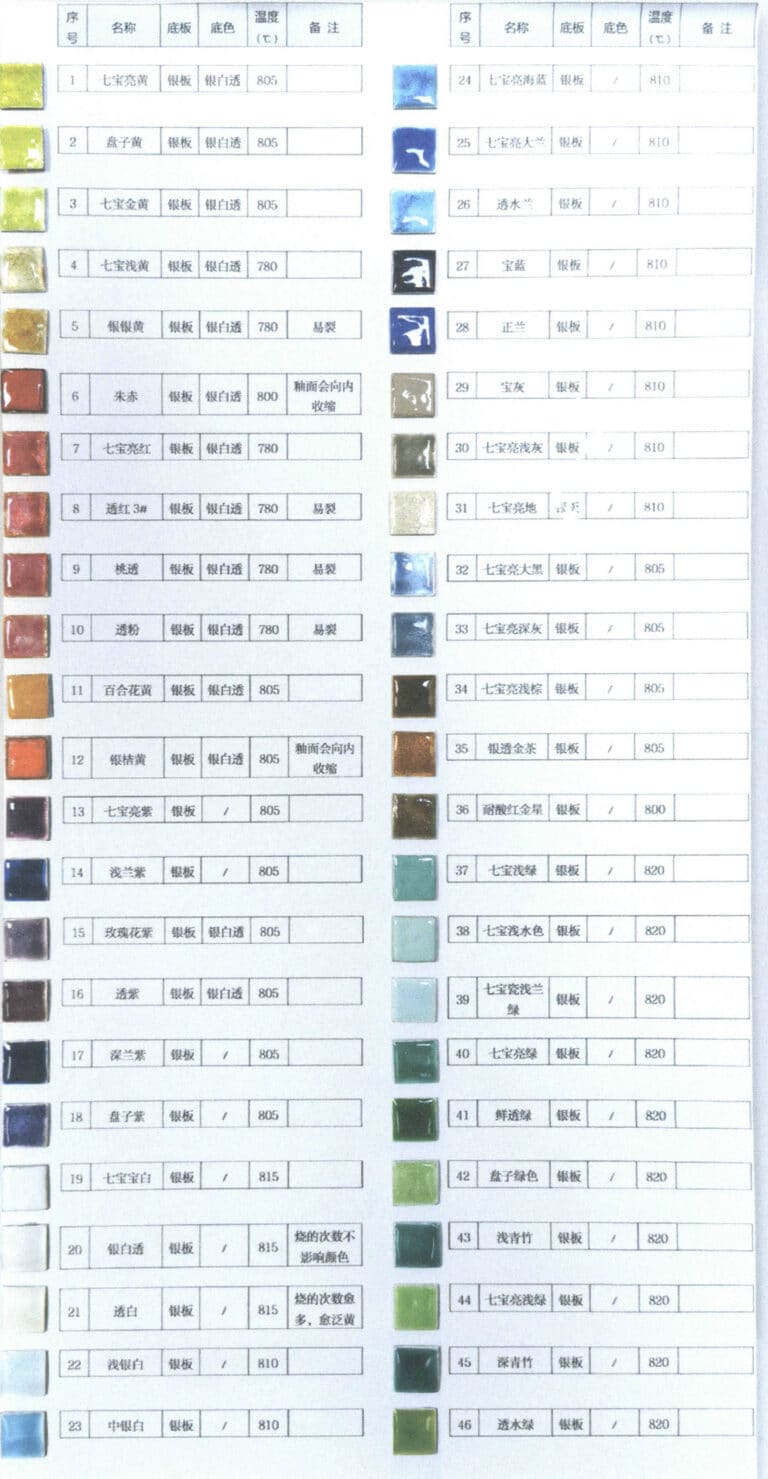

A set of fired, standard, and reasonably ordered swatches can provide great convenience for enamelling. Figure 1-27 shows the enamel swatches in the jewellery studio of the Academy of Arts & Design at Tsinghua University; you can see sample colours on the left and corresponding numbers behind them, so when selecting a colour, you can first find the needed shade by the sample and then use the number behind it to locate the corresponding glaze.

Figure 1-26 Several glaze powders and colour swatches

Figure 1-27 Glaze colour chart

4. Preparation of Glaze Before Firing

Enamel glaze needs to be ground and washed before firing in order to grind the glaze’s crystalline particles finer, remove various impurities from the glaze, and achieve better colouring effects after firing.

(1) Tools for Grinding and Washing

The tool used in the grinding and washing process is a mortar. The mortars used are either porcelain or agate; glass mortars must not be used. Figure 1-28 shows an agate mortar, and Figure 1-29 shows a porcelain mortar.

Figure 1–28 Agate mortar

Figure 1–29 Porcelain mortar

Porcelain mortars are generally used during study or in classes. Agate mortars are more expensive and smaller in size, making them better suited for use when creating works; moreover, agate mortars are hard and dense, allowing glazes to be ground finer and cleaned more thoroughly in a shorter time.

It is best to use distilled water for the grinding and cleaning process, because tap water has a complex composition that can affect the color performance of glazes. Choose distilled water that does not contain calcium or magnesium ions (chemically pure, medical, or otherwise labelled distilled water) to minimize external influences on the firing process and achieve better results. Figure 1–30 shows the composition table of distilled water suitable for grinding and cleaning, which does not contain calcium or magnesium ions.

(2) Specific Steps for Grinding and Washing Glaze

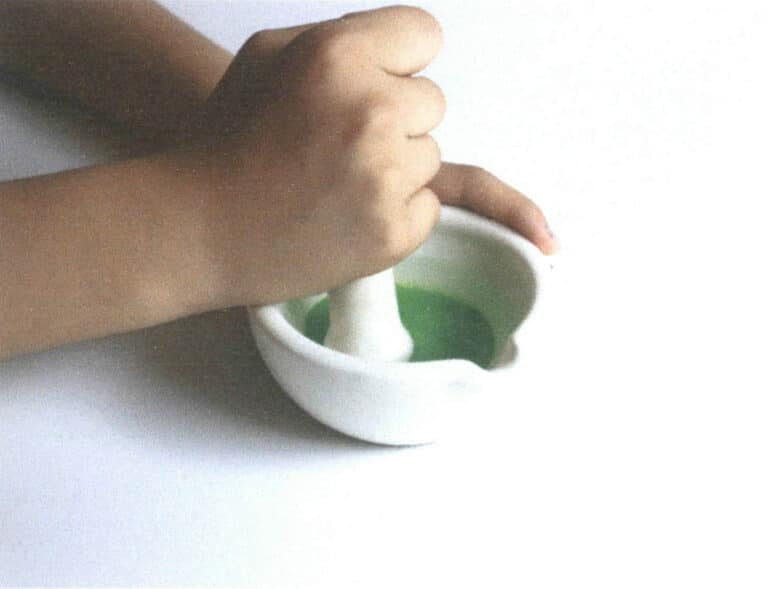

STEP 01

Place an appropriate amount of glaze into the mortar and add distilled water. Do not add too much water; slightly less than half the capacity of the mortar is sufficient. Use the pestle to stir slowly in a clockwise direction, and at the same time, apply pressure to grind, breaking the particles apart. The grinding time lasts about 1~2 minutes, as shown in Figure 1–31.

STEP 02

Let the ground glaze settle for a moment until most of the glaze in the water has sunk to the bottom. Pick up the mortar and slowly pour off the upper portion of the water. Be sure to move gently at this stage to avoid pouring out the glaze still suspended in the water, as shown in Fig. 1–32.

Figure 1–31 Step 1 for grinding glaze

Figure 1–32 Step 2 for grinding glaze

STEP 03

Repeat STEP 01 and STEP 02: add water, grind, let it settle, and pour off the water. As the number of grindings increases, the water in the mortar will become clearer. When the glaze is sufficiently clean, perform the final wash. Unlike the previous steps, the last time you do not need to grind vigorously; stir the glaze in the water so that any remaining impurities float to the surface and then pour them off. In Fig. 1–33, the glaze in the mortar has been washed clean.

Notes : There is no fixed rule for how many times the grinding step should be repeated; it is up to the maker to decide. In theory, the more thorough and cleaner the grinding and washing, the fewer impurities remain in the glaze, and the better the colour rendering after firing.

Thorough grinding and washing can largely remove impurities from the glaze. When relatively large glaze particles are ground down, impurities originally trapped in the crystals can then be washed away.

Even when using Japanese glaze that are already very fine, to maximize firing quality, they still need to be ground and washed before firing. If this step is not taken seriously, bubbles and some impurities are often found in the enamel after firing; after polishing, these form tiny cavities or black spots. These small cavities are called ” sand holes” in the cloisonné industry. The coarser the glaze particles and the more impurities present, and the larger the area of the piece, the greater the likelihood of “sand holes” appearing; sometimes this can even cause the enamel to crack. Of course, some makers skip this step and add plain water directly to the enamel for use.

Section III Types of Metals Suitable for Enamel Firing

As mentioned earlier, true enamel can only be produced by applying enamel glaze to a metal substrate and firing the two together at high temperature. Therefore, enamelwork cannot exist independently of metal; the metal in an enamel piece is the substrate to which the enamel adheres. However, not all metals are suitable for firing enamel. Some metals bond very well with enamel glaze and form a very strong bond after firing; some metals cannot bond with enamel glaze at all; and some metals have a certain affinity for enamel glaze but are difficult to fire with and require special conditions.

Metals that bond very well with enamel glaze and are frequently used for firing enamel include gold, silver, and red copper. The term gold here includes pure gold and various K golds, such as 22K, 18K, 14K, or 9K. In addition to yellow gold, platinum and rose gold can also be used for firing enamel. Silver includes various alloys, with the most common being fine silver, 950 silver, or 925 silver. Red copper refers to pure copper. Figure 1–34 shows the different effects of a French No. 46 transparent enamel glaze fired on silver, 24K gold, and red copper substrates.

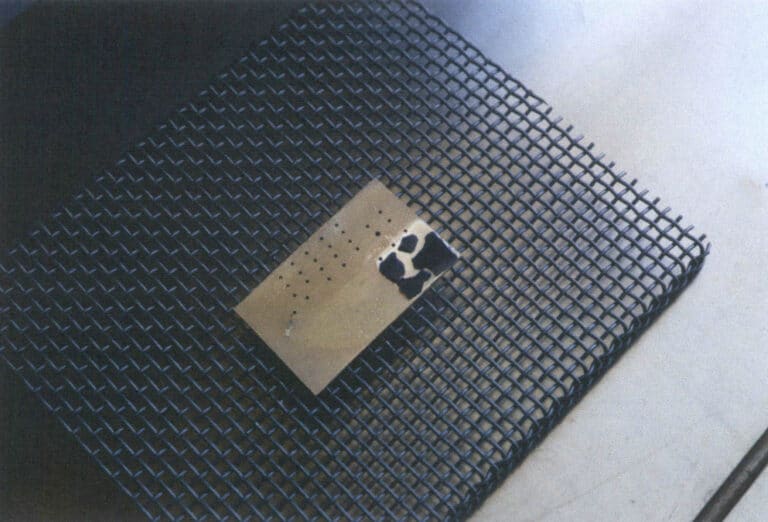

Metals that cannot bond with enamel glaze at all include brass. If enamel is fired on a brass substrate, the enamel glaze will blacken and flake off; Figure 1–35 shows the effect of firing enamel on a brass substrate. When enamel is fired on brass, the glaze and metal cannot bond at all, and once the metal substrate cools, the enamel will spall.

Figure 1–34 Different effects of firing the same enamel glaze on silver, 24K gold, and red copper substrates

Figure 1–35 Enamel glaze spalling on a brass backing

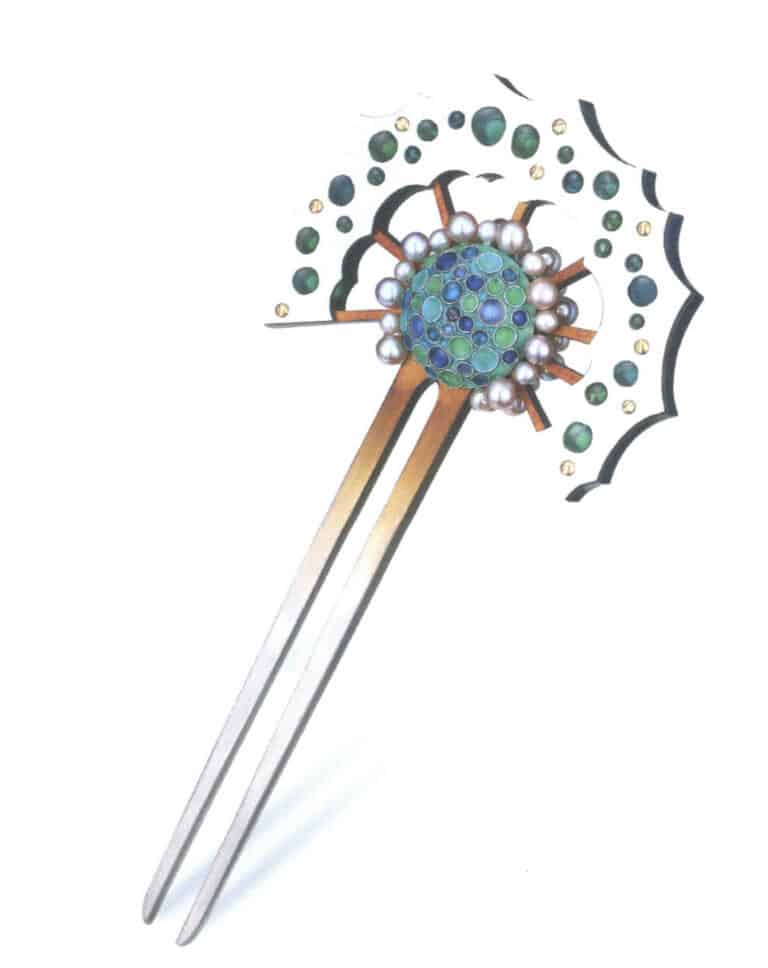

Other metals, such as titanium, have some affinity with enamel glaze, but firing is more difficult. The oxide layer that forms on titanium when heated interferes with the bonding between the metal and the glaze. Some artists fire cloisonné enamel on titanium, but the enamel glaze will only bond when the area of the titanium is very small. Shown in Figure 1–36 is a hairpin made with plique-à-jour and cloisonné techniques, in which the fan-shaped plique-à-jour enamel was fired onto titanium.

Similar to titanium, iron can only be used as a substrate for firing enamel under specific conditions and with specialized methods. Enamelware commonly found in daily life, such as the enameled cast iron pot shown in Figure 1-37, is produced in factories using specialized equipment and techniques where the enamel is fired onto an iron base.

Figure 1–36 Hairpin "Ocean Series III"

Figure 1–37 Enamel cast-iron pot