What Are the Step-by-Step Techniques for Metal Chasing and Repoussé?

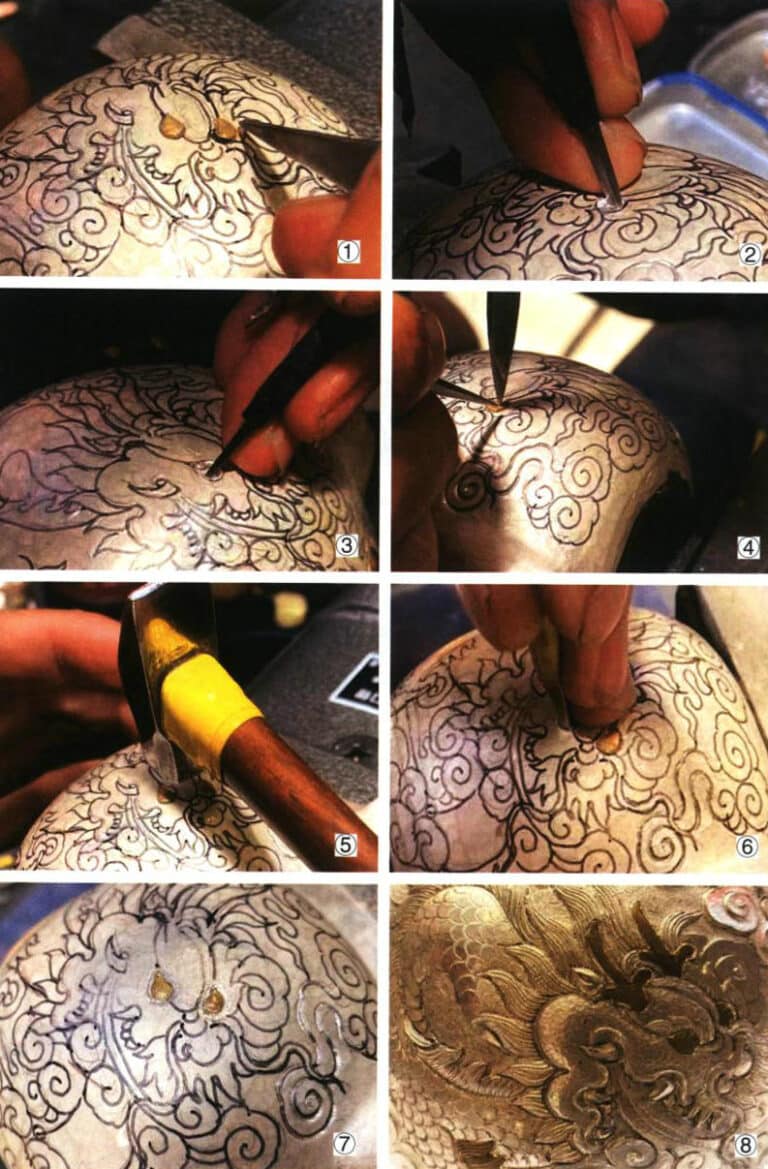

Chasing and Relief Techniques Teaching Case Studies

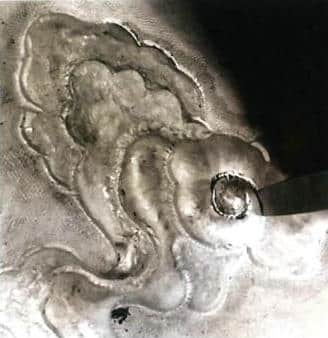

Effect after embossing

Πίνακας περιεχομένων

Section I Cloud Patterns

(1) Pattern layout

Use a pencil, grease marker, or other outlining tools to draw the pattern to be chased on the silver sheet, or paste a printed drawing onto the silver. These patterns can be very detailed or merely approximate shapes or structural lines, and are drawn mainly according to the craftsperson’s own requirements.

Cloud motifs are a traditional Chinese pattern; because they are a homophone of “yun” (fortune/movement), decorating objects with cloud patterns can express people’s longing for a good life. In Figure 5-1, the cloud motifs are mostly composed of smooth, curving lines. When laying out the pattern, you should not only draw the basic outer shape of the clouds but also sketch the layered effect within to enrich the visual experience.

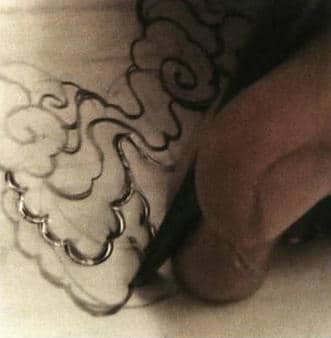

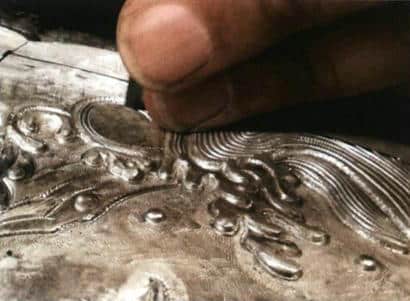

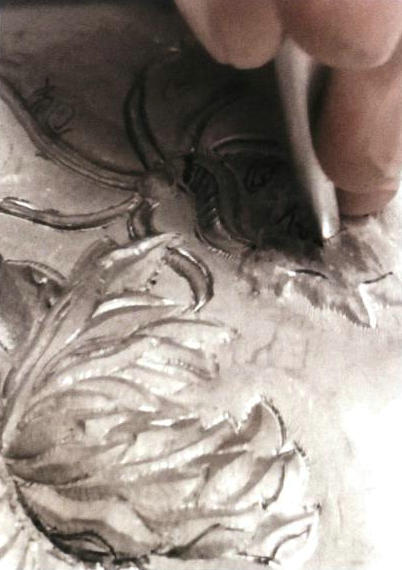

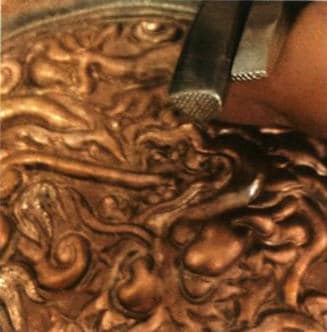

(2) Line chasing

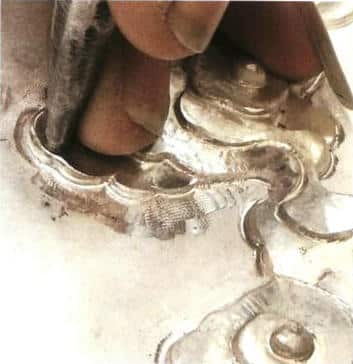

Use straight chisels and curved chisels of different curvatures and sizes to chisel the pattern lines on the silver sheet once. Primarily use slow straight chisels and slow hollow chisels to chisel the larger structural lines and the most pronounced undulating layers in the pattern. Using slow chisels helps when later creating spatial relief on the silver sheet. When chiseling cloud patterns with curved chisels (Fig. 5-2), for the central curled head of the cloud pattern (Fig. 5-3), because its curvature is large, you can lift one end of the curved chisel slightly while chasing the line; this makes the line more fluid and natural and chisels out a gradually narrowing spiral line.

Figure 5-2 Chasing the outer contour of the cloud pattern

Figure 5-3 Chasing the curled head of the cloud pattern

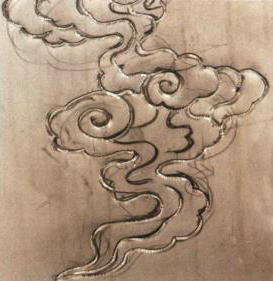

Figure 5-5 Cloud pattern after line chasing (front)

Figure 5-6 Cloud pattern after line chasing (back)

(3) Flattening along the outlines

After line chasing, only sunken traces remain on the silver sheet. At this stage, place the silver sheet face up on a flat steel plate and use a round- or square-headed embossing chisel to press the areas outside the pattern flat along the outer contour line (Fig. 5-7). With the action of the hammering, the parts of the pattern that have not been pressed will naturally rise.

Pay attention to pressing down the front corners as well; you can use a small teardrop-shaped embossing tool to flatten them, making the main form appear complete and clear (Fig. 5–8).

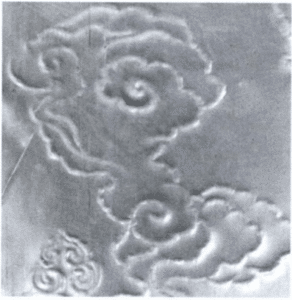

Compared with the image of the back of the silver sheet after line chasing, after flattening along the lines, the main cloud pattern protrudes outward more and is clearer (Fig. 5–9).

Figure 5-7 Flattening along the outlines with a embossing chisel

Figure 5-8 Main form is clear

(4) Punching on the reverse

After the silver sheet has been annealed and softened, select suitable form-establishing chisels based on the already chased pattern lines; commonly use chisels with ball- or teardrop-shaped heads for embossing or other slow chisels, to form the parts of the pattern that will become the highest points or have the richest spatial modeling pushed out from the back (Fig. 5-10). In the cloud pattern, the overall form rises around the curled-head section, with the curl at the highest point. Note to push out layer by layer following the top-to-bottom, inside-to-outside order so that the layering is clear and distinct. Also, take care not to apply too much force or strike the same spot repeatedly, as this can thin or crack the silver sheet and affect subsequent work.

(5) Surface flattening

Starting from the edge of the cloud motif, use dotted chiseling or embossing chiseling to press outward and flatten the surrounding uneven areas, cover blemishes, and clarify the main pattern.

At this point, the pattern becomes more distinctly layered (Fig. 5-11).

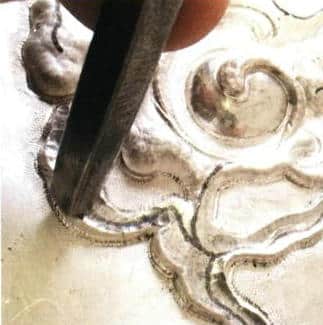

(6) Major outlining on the front

Use curved chisels and line chisels to re-accurately delineate the cloud-pattern shapes, making the structural lines of the design—which were blurred by the back punching—clearer. In areas needing more lifting, such as the curled ends of the cloud motifs, you can outline multiple times or cut deeper (Fig. 5–12) to prepare for embossing.

After the major outlining on the front is completed, the cloud-pattern shapes are clearer, but the interior still has uneven undulations and must be refined through subsequent embossing.

(7) Shaping

First, use the small embossing chisel to deeply shape the undulating parts of the cloud pattern (Fig. 5–13). If you want to clarify the spatial layers, you can pound along the edge of each layer of cloud from the inside out; this produces a more three-dimensional form and stronger spatial contrast.

Then use the large embossing chisel to start from the areas worked by the small chisel and flatten the remaining parts outward (Fig. 5–14). Take care to flatten layer by layer to make the spatial hierarchy clear.

Figure 5-13 Small embossing chisel shaping

Figure 5-14 Large embossing chisel shaping

(8) Leveling with the small embossing chisel

Use the small embossing chisel to flatten the impressions left by the previous engraving (Fig. 5–15).

After local refinement, the layering created by the initial routing can be seen from the side (Fig. 5-16) to have a clear spatial relationship after embossing treatment (Fig. 5-17).

Figure 5-15 Small embossing chisel leveling

Figure 5-16 Partial cloud pattern

Section II Fire pattern

(1) Pattern layout

The layout method is the same as for cloud patterns. The fire motif is a traditional Chinese pattern; in Figure 5-18, the fire motif is depicted as radiating flames arranged around a central swirling fire mass. The most distinctive features of the fire pattern are the curled fire clusters in the lines near the vortex center and the flame shapes that float like clouds; these shaping characteristics must be emphasized when drawing.

(2) Line chasing

Use a flat chisel and slow-bend chisels of different curvatures and sizes to trace the pattern lines on the silver sheet once, focusing on the major structural lines and the most pronounced undulation layers in the pattern (Fig. 5-19). Using slow chisels helps create spatial uplift on the silver later. After completing the first pass of line chasing, perform a second pass to smooth out the uneven pits produced by the first pass; this is called “ground leveling.” The center of the fire motif is a curl-shaped pattern, which can be traced using a large, gently curved chisel or a line chisel; the remaining parts have shorter curves with greater curvature, so a small curved chisel may be used. When chasing, the junctions between lines must be tightly joined.

The fire motif has a certain relief quality, so it requires repeated application and removal of adhesive. After tracing the lines, remove the silver sheet from the adhesive board; at this point, the structural lines and general contours of the pattern can be clearly seen from the back (Fig. 5-20).

Figure 5-19 Patterning after line chasing

Figure 5-20 Silver piece after line chasing (back)

(3) Flattening along the outlines

Place the silver sheet with its front side up on a flat steel plate and use a chasing punch with a round or square tip to press-chase, flattening the areas within the pattern along the outer contour lines (Fig. 5-21). At this stage, a dot-pattern chisel can be used to flatten any unevenness around the fire pattern, creating a matte texture that makes the fire pattern clearer; with continued hammering, the fire pattern will naturally become slightly raised (Fig. 5-22). Viewed from the reverse side (Fig. 5-23), the leveled fire pattern is even more distinct.

Figure 5-22 Flattening along the outlines (front)

Figure 5-23 Flattening along the outlines (back)

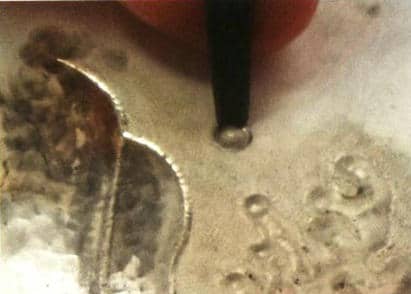

(4) Backside punching

In order to make the relief on the front more pronounced, first use small spherical or square embossing chisels from the back to stamp the sharper corners within the fire pattern (fig. 5-24). Be careful not to strike too hard or to hit the same spot repeatedly, as this can thin or rupture the silver sheet and affect subsequent work.

After the local shaping and stamping are completed, use a larger embossing chisel to lift the fire pattern as a whole. Use the whirlpool center of the fire pattern as the visual focal point, making it the highest spot by punching it out from the back with a large embossing chisel (fig. 5-25).

The main parts of the fire pattern should be formed by chisel from the back with chisels to create convex areas, producing contrast with the surrounding flat surfaces and providing the spatial basis for subsequent embossing.

After the back has been hammered into shape and the solder removed, the front will show the fire patterns with some relief, but because the highs and lows are irregular (Fig. 5–26), the contours formed by the first line chasing have become blurred; therefore, shaping must be done from the front.

Figure 5-24 Small embossing chisel back punching

Figure 5-25 Large embossing chisel back punching

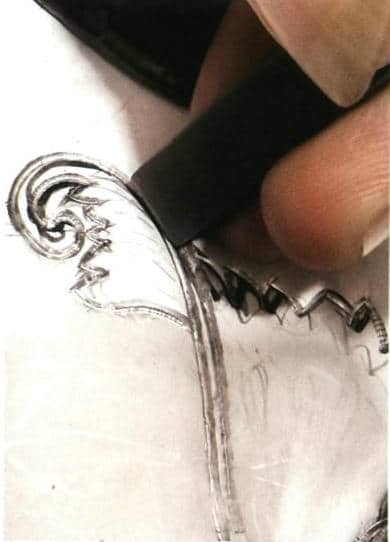

(5) Major outlining on the front

Before applying the adhesive, anneal the silver sheet so it becomes soft again. Building on the punched form, perform another line chasing using line chisels or various curved chisels to clarify the pattern’s form.

A curved chisel can be used to finely render the curled parts of the pattern (Fig. 5–27). When outlining, strive to make the lines flow smoothly and naturally.

After laying out the large lines from the front, the fire pattern still appears uneven and chaotic in its layering; it must now be refined with embossing chisels.

(6) Shaping

Begin by using a large embossing chisel to flatten the protruding forms and to roughly shape the pattern’s spatial forms (Fig. 5-28).

Then use a small embossing chisel to create finer edge undulations, such as the boundaries of the fire pattern (Fig. 5-29).

Figure 5-30 on the right is a square, large embossing chisel, used for embossing of large shapes; on the left is a teardrop-shaped embossing chisel, whose pointed angle is more suitable for depicting fine-shaped detailing.

Figure 5-28 Large embossing chisel shaping

Figure 5-29 Small embossing chisel shaping

(7) Embossing and Trimming

Choose an appropriately sized small embossing chisel to emboss the pattern. For example, the sharper, slimmer flames in a fire pattern are better shaped using a small embossing chisel (Fig. 5–31).

Select a suitable small embossing chisel to trim the sides of raised patterns (Fig. 5–32).

The chisels used for shaping, embossing, and trimming are shown in Fig. 5–33.

After shaping, embossing, and trimming, the flame pattern is completed (Fig. 5-34).

Figure 5-31 Small embossing chisel for embossing

Figure 5-32 Small embossing chisel for trimming

Figure 5-33 Chisels used for embossing and trimming

Figure 5-34 Completed flame pattern

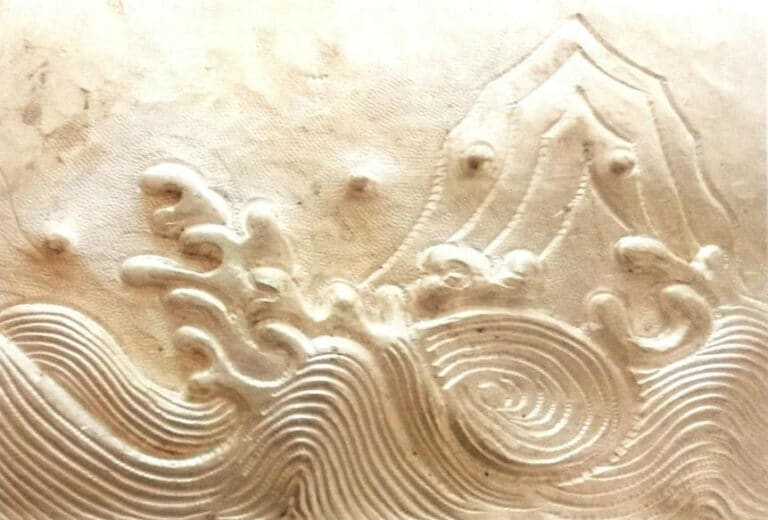

Section III Landscape Pattern

(1) Pattern layout

Draw the water-pattern (Fig. 5–35) and lay it out; the laying-out method is the same as for cloud patterns.

(2) Line chasing

Use a straight, slow chisel and slow, bent chisels of different curvatures and sizes to chisel the landscape pattern lines on the silver sheet once over, focusing mainly on the larger structural lines in the pattern and the lines with the most pronounced undulations (Fig. 5–36).

The four chisels in Fig. 5–37 are slow chisels often used for patterns with many curved lines. The second chisel from the left in the figure is the largest slow-bent chisel, with a very blunt arched tip.

After chasing the lines, remove the silver sheet from the adhesive board. At this point, you can clearly see the structural lines and the general outline of the landscape pattern from the back (Fig. 5-38).

Figure 5-36 Line chasing

Figure 5-37 Slow chasing

(3) Flattening along the outlines

Place the silver sheet face up on a flat steel plate, and use round or square embossing chisels to flatten the areas inside the pattern along the outer contour lines; the parts of the pattern that are not planished will naturally rise (Fig. 5–39).

(4) Punching from the back

After annealing the silver sheet until it softens, select suitable form-establishing chisels according to the already chased landscape lines—commonly ball-shaped, teardrop-shaped embossing chisels, or other slow chisels—and punch from the back the spots that will become the highest points or the areas with the richest spatial modeling in the landscape (Fig. 5–40). Be careful not to strike too hard or repeatedly at the same point, as this can thin or crack the silver sheet and affect subsequent work.

(5) Second front-side line chasing

Before applying the adhesive, anneal the silver sheet to restore its softness. Use a linear chisel to first delineate the raised, uneven shapes formed by the punches (Fig. 5-41). Use a slow chisel to chase the edges of the domed hemispherical forms (Fig. 5-42), making the water-drop shapes clearer.

Figure 5-41 Front large line chasing

Figure 5-42 Water droplet line chasing

(6) Embossing

Use embossing chisels to shape the lines at the edges of patterns and to model the raised undulating spaces of the pattern into concrete forms and foreground-background spatial relationships. Use a small embossing chisel to form the shape of the waves (Fig. 5-43).

For treating the background surface, traditional methods use bead chisels or dot-pattern chisels. These textures produce a dense pattern on the background that diffuses light, making the main subject clearer. Embossing also helps mask pits and irregularities; after all, it is very difficult for a craftsman to hammer a large background area completely flat, and doing so would require a great deal of time and craftsmanship.

As can be seen in Figure 5-44, after embossing, the wave forms are clear, and the edges are sharp.

Figure 5-43 Small embossing chisel chasing water splashes

Figure 5-44 Effect after embossing sea wave water splashes

Figure 5-45 Using a square embossing chisel to chase the shape starting from the base layer

Figure 5-46 Using a square embossing chisel to stamp the mountain shape upward

Then use various form-establishing chisels to stamp out the form of the water swirls (Figure 5-47).

And use embossing chisel to shape the spatial forms and foreground–background relationships of the landscape motif, preparing for the subsequent fine chasing details.

After the spatial forms are shaped, according to the motif’s design and stylistic characteristics, use rapid chasing to cut silk-like water lines (Fig. 5–48). The arrangement of the lines depends on the artisan’s experience, their understanding of the form, and their artistic expression. The richness of the detailed rendering is precisely the charm of the chasing and relief craft.

Figure 5-47 Embossing chisel shaping water whirl patterns

Figure 5-48 Quick chisel embossing water patterns

(7) Removing the adhesive

After the chasing and relief is completed, remove the resist and use acid pickling to remove stains from the surface of the silver sheet, then check for any defects or omitted, unchased areas. The chased landscape pattern is shown in Fig. 5-49.

Copywrite @ Sobling.Jewelry - Κατασκευαστής προσαρμοσμένων κοσμημάτων, εργοστάσιο κοσμημάτων OEM και ODM

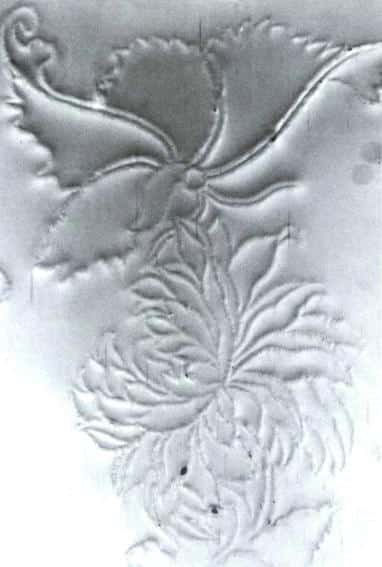

Section IV Flower and Butterfly Pattern

(1) Pattern layout

Using a pencil, oil-based pen, or other marking tools, draw the floral and butterfly pattern on the silver sheet (Fig. 5-50). You can also paste a printed design onto the silver sheet.

(2) Line chasing

Use a slow-line chisel and curved chisels of different curvatures and sizes to chase the pattern lines on the silver sheet once (Fig. 5-51), focusing mainly on the larger structural lines of the pattern and the most pronounced lines of undulation and layering. After outlining is completed, the general contour of the floral and butterfly pattern will be visible (Fig. 5-52).

After chasing the lines, remove the silver piece from the adhesive plate. At this point, you can see the clear structural lines of the pattern and the general sense of movement from the back (Fig. 5–53).

Figure 5–51 Partial view of the line chasing

Figure 5–52 Completed flower line chasing

(3) Flattening along the outline

Line chasing leaves indented traces of the pattern on the silver sheet; at this point, the silver sheet should be placed face up on a flat steel plate, and using a chasing tool with a round or square face, press-chase and flatten the areas inside the pattern along the outer contour lines. As shown in Fig. 5–54, areas that have not been pressed will naturally be raised.

(4) Punching from the reverse

After the silver sheet has been annealed and softened, use the lines of the already chased pattern to select suitable forming chisels. Typically, choose chisels with spherical or teardrop heads for embossing or other slower chisels, and push up the areas that will become the highest points of the flower-and-butterfly pattern or the regions with the richest spatial modeling from the back (Fig. 5–55).

(5) Major outlining on the front

Anneal the silver again to restore a soft state. Glue the sheet, then use liner chisels to retrace the previously line chasing, carving more deeply to refine the modeling (Fig. 5–56).

Figure 5-55 Punching from the reverse

Figure 5-56 Major outlining on the front

(6) Flattening surfaces

Use the chisels shown in Fig. 5-57 to level flush the surrounding area of the main floral leaves and refine the shape. The chisel on the left is a teardrop-shaped embossing chisel; the one on the right is an olive-shaped stippling chisel, used to create texture effects in floral and butterfly patterns.

(7) Detailed relief chasing

Use square or round embossing chisels to give the initially punched shapes their first three-dimensional form (Fig. 5-58), so the pattern shows a definite relief and spatial relationship.

Figure 5-57 Chisel used for flattening surfaces

Figure 5-58 Detail relief chasing

(8) Small embossing chisel for embossing

Use a small embossing chisel to trim the edge lines (Fig. 5-59), and shape the areas of the silver sheet that are uneven into clear, definite forms.

(9) Large embossing chisel for shaping

Compared with floral patterns, leaf patterns have larger areas in each part, making them suitable for three-dimensional shaping with a large embossing chisel (Fig. 5-60).

Figure 5-59 Small embossing chisel for embossing

Figure 5–60 Large embossing chisel for shaping

(10) Flattening with the large embossing chisel

At the edges of the main pattern, use the large embossing chisel to compact and level the surface (Fig. 5–61), accentuating the three-dimensional effect of the main relief.

(11) Embossing

First, use a shaped chisel to deeply model the protruding edges of the pattern so the overall form is more refined. Figure 5– 62 shows a shaped chisel with a central notch; using it, you can chisel relief forms with smoother side profiles.

Then use various types of line chisels to decorate and detail the butterfly pattern (Fig. 5–63).

Figure 5-62 Irregular-shaped chisel embossing

Figure 5-63 Line chisel embossing

(12) Adhesive removal

Use acid to remove stains from the silver sheet surface and check whether the sheet has any holes or areas that were missed by chiseling. The chiseled floral-and-butterfly pattern is shown in Fig. 5–64.

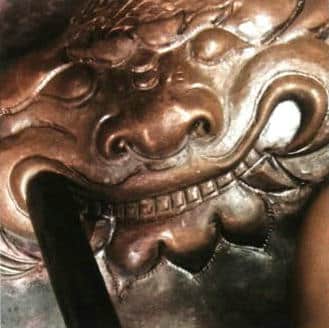

Section V Lion Pattern

(1) Apply adhesive to the stamping die

From the stamping die, one can roughly make out a lion’s head. The die stands out strongly overall and has a pronounced bas-relief effect, but the boundaries of the various modeled parts are indistinct (Fig. 5-66). To obtain a lifelike lion head pattern, these stylistic features of the lion head must be carved in depth. First, apply adhesive on the die.

(2) Sketching and rough outlining with the large line chisel

First, sketch the decorative pattern on the stamping die with a pencil or oil-based pen. For example, personify the lion’s head: draw tight, dense eyebrows above the eyes, sketch clusters of closely connected, curled mane around the face, and depict the lion’s sharp fangs—laying the groundwork for later embossing and shaping.

After all decorative details have been sketched, use a large line chisel to outline the lines; ensure the stroked lines are smooth and clear to further define the lion head’s form (Fig. 5–67).

Figure 5-66 Stamping Die

Figure 5-67 Large line chisel outlining

(3) Shaping with embossing chisel

After the main outlining with the large chisel is complete, use embossing chisels to sculpt the specific spatial forms. Before embossing, determine the visual focal point and make it the most prominent part of the entire pattern. In the lion head motif, the facial features can serve as the visual center—use embossing to reinforce the spatial contrast of highs and lows there. The face should be the highest point in the lion head design; the surrounding mane should not be higher than the face, otherwise it will distract from the visual center.

(4) Detailing

Use various embossing chisels and line chisels to emboss details on the teeth and whiskers; pay attention to sparsity and placement. As shown in Fig. 5-68, use a round embossing chisel to punch the lion’s mouth corners so the adjacent lips can be raised; to enrich the layers, the mouth corners can be punched into inward-curving spiral shapes. In addition, smaller line chisels can be used to chase the lion’s neat teeth. Observe closely: the lion’s nose and eyes form a single mass, so to better convey the lion’s majestic bearing, punch more along the sides of the eyes and nose to give greater lifting in height, then perform fine carving from the top.

(5) Embossing

First, use a specially made scale-pattern chisel to emboss the lion’s forehead pattern (Fig. 5-69); ensure each scale overlaps and interleaves unevenly to create a sense of layering.

Chisel the details of the lion’s eyebrows, teeth, and whiskers. The facial decorations of the lion in Fig. 5-70 can be achieved by lightly tapping with a pointed chisel; in addition, use a three-line chisel or a regular line chisel to notch the texture of the lion’s eyebrows and the surrounding mane. When depicting the forehead mane, shape it into a whirl pattern for a better decorative effect, and chisel the whirl to convey a layered, overlapping feel. In this way, each part will have clear layers and the lion will appear lifelike.

Figure 5-69 Scale-pattern chisel embossing

Figure 5-70 Lion facial details

(6) Removing the adhesive

Use high heat to burn the resist on the engraved copper sheet (Fig. 5-71) until it carbonizes, then remove the adhesive with a copper brush or steel wool.

Then boil the cleaned copper sheet in dilute sulfuric acid until it whitens; with this, the piece is finished.

The above methods can be used to chase various lion patterns (Fig. 5-72).

Figure 5-71 Copper sheet waiting for adhesive removal

Figure 5-72 Other lion patterns

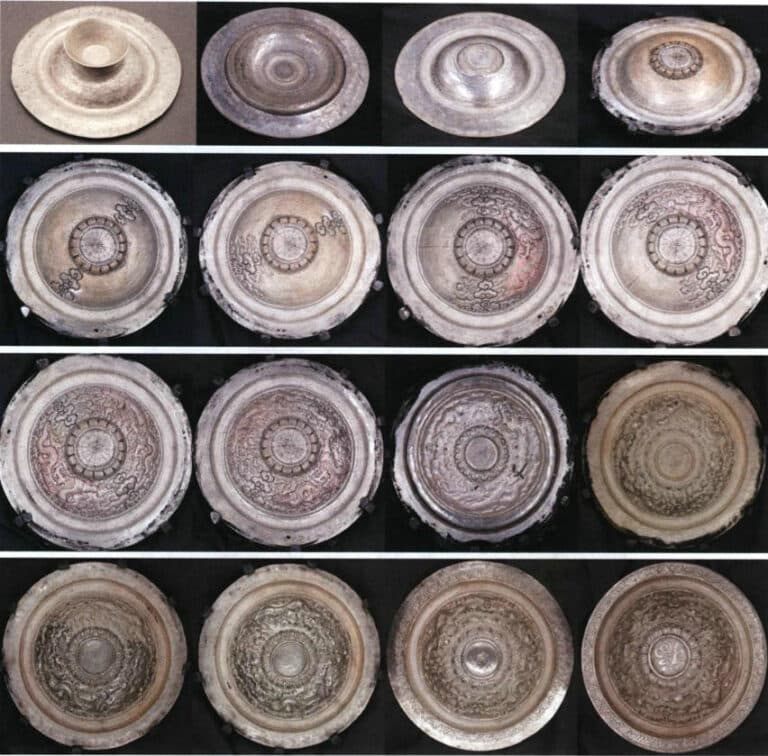

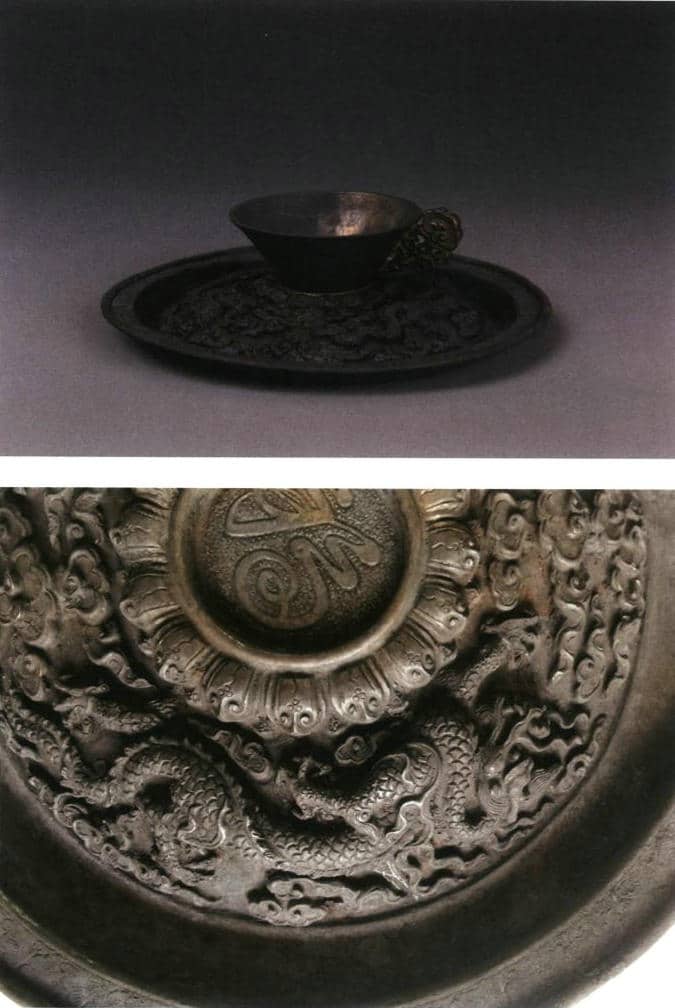

Section VI Circular Dragon Pan Pattern

(1) Applying adhesive on stamping plate and form punching

As can be seen from Fig. 5-74, the stamped blank has taken shape, with a basic spatial structure in place; the dragon head, claws, and pearl can be roughly distinguished, but fine details — such as the dragon’s facial features, hair, and scales — will need later refinement and carving. Apply adhesive to the copper sheet, and after the copper has been annealed and softened, choose suitable form-establishing chisels based on the existing lines to bring out the raised parts of the dragon pattern; pay attention to the relative heights when forming.

(2) Large chisel for outlining

The outer parts of the dragon motif and the more gently curved sections of the dragon pattern, such as the body, can be outlined using a large line chisel to clarify the dragon’s shape (Fig. 5-75).

Figure 5-74 Stamping plate

Figure 5-75 Large-line chisel line chasing

(3) Small-curved chisel chasing line

The dragon’s head in the pattern occupies the central position; it is the visual focal point of the entire motif and also the highest point of the relief. There are many curved shapes here, such as the dragon’s eye, nose, and mouth. At this stage, small curved chisels can be used to form these characteristic shapes (Fig. 5–76). When chasing the lines, pay attention to the continuity of the strokes; you can gently lift one end of the line chisel to avoid leaving messy gouge marks on the work.

After line chasing, the dragon pattern’s shape becomes even clearer (Fig. 5–77). The line chasing provides a foundation for the subsequent embossing.

Figure 5-76 Line chasing with small line chisel

Figure 5-77 Completed line chasing

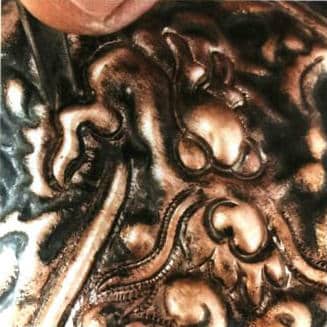

(4) Background texturing with embossing chisels

Use a dot-pattern chisel to chase the very base of the dragon pattern, creating a dense texture on the background that scatters light diffusely so the main subject appears clearer; it also helps to hide blemishes. Figure 5–78 shows teardrop and linear dot-pattern chisels. The teardrop dot-pattern chisel can be used not only for large-area embossing but also to render the base-layer corners in the pattern. For example, the angles between dragon hairs can be treated with the pointed part of the teardrop dot-pattern chisel.

(5) Embossing with embossing chisel

Use a embossing chisel to shape the lines at the edges of the pattern and the raised undulating surfaces into specific forms and spatial relationships. Beforehand, carefully consider the relationship between the visual focal area and the surrounding levels of height. From Figure 5-79, the dragon’s head is the visual center and should be rendered as the highest and most detailed part of the entire pattern, with the heights of the remaining parts decreasing step by step.

Figure 5-78 Dot-pattern chisel

Figure 5-79 Effect after embossing

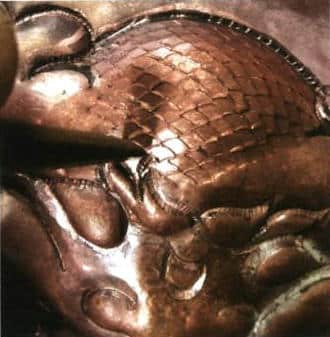

(6) Chasing dragon scales with scale-pattern chisel

Use a specially made scale-pattern chisel to carve the dragon scales, taking care that each scale is chiseled in an overlapping, staggered manner to create a sense of layering (Figure 5-80). When striking the chisel, be decisive and swift, avoiding repeated blows on the same scale as much as possible to prevent messy cut marks.

(7) Three-line chisel embossing

Use a three-line chisel to chisel the dragon’s hair (Fig. 5–81). Please pay attention that the arrangement of each strand of hair is coherent and smooth, the spacing between the lines is even, and avoid crossing them as much as possible.

Figure 5-80 Chasing dragon scales with scale-pattern chisel

Figure 5-81 Three-line chisel embossing

(8) More details of chasing the dragon

Use embossing chisel to make the front-to-back positional relationships the dragon’s facial features: eyes, mouth, nose, and whiskers clear.

The partial effect after embossing is shown in Fig. 5-82. The before-and-after effects of the stamp plate chasing are shown in Fig. 5-83.

Figure 5-82 Close-up view of completed embossing

Figure 5-83 Effect illustrations of the stamp plate before and after chasing

Figure 5–84 Process of making a dragon basin cup

Figure 5–85 Antique-style dragon basin

Section VII Gold-Inlaid Technique

From ancient times to the present, craftsmen have often used metals for multi-layered, multicolored artistic expression, such as gilding, inlaying gold and silver, raised inlay, textured inlay, and the inlaid-gold technique developed from the engraving-and-flowering (zhanhua) craft. The common features of these combined metal techniques are as follows.

(1) The connections between metals are basically all cold joints.

(2) Relying on differences in hardness and ductility between metals, perform various methods of cold joining.

(3) All inlaid metals exhibit characteristics of being slender, small, and thin.

The following is the process of inlaying brass into the surface of a silver teapot using different tools (Fig. 5–87).

(1) Determine the pattern to be inlaid, carve it out of the brass sheet with a carving chisel, and place it on the surface of the silver teapot at the intended inlay position for confirmation and adjustment (Fig. 5–88①).

(2) Use a specialized fine chisel to chisel the spots on the silver pot where inlaying will be done; use a fine-line chisel to outline the contour, then use an oblique pressure chisel to chisel the area inside the contour downward (Fig. 5–88 ②③), leaving space equal to the thickness of the metal to be inlaid.

(3) Use differently shaped embossing chisels to level and smooth the sunken surface and edges.

(4) Place the brass pieces to be inlaid on the sunken surface for adjustment (Fig. 5–88 ④), aiming for a seamless fit at the edges.

(5) Once secured, lightly tap the brass with a small hammer so the pieces closely adhere as a whole (Fig. 5–88 ⑤).

(6) Use embossing chisels of different shapes to press along the edges of the inlaid metal downward so that it is fully embedded into the sunk surface (Fig. 5-88⑥⑦).

(7) Repeatedly press the brass edge and the edge along the sunk surface, relying on the overlapping of the metal edges to tightly compress the two pieces of brass together (Fig.5-88⑧).